LATE PERIOD HITCHCOCK: TORN CURTAIN, FRENZY, & FAMILY PLOT by Craig Hammill

Late period work by any director usually gets met first with disappointment then respectful reappraisal, rarely with wild acclaim.

Filmmaker Quentin Tarantino is so conscious of the usual trend of diminished quality that he continues to assert his next movie (currently in pre-production), his 10th, will be his last. A keen study of how filmmographies go, Tarantino intends to go out on top with a bullet proof body of work. No surprise, he has also started a family now and may want to be the kind of present father and husband many directors are not.

So it’s with some surprise that in revisiting three of Hitchcock’s final four films-1966’s Torn Curtain, 1972’s Frenzy (the megahit of the trio), and 1976’s final bow Family Plot (the discovery for any Hitchcock fan who has not yet seen it), this writer found himself impressed with just how much gas Hitchcock had left in the tank. These final movies, while flawed at varying levels, find a moviemaker experimenting, generating great ideas for sequences, and thrilling in new ways to hone their craft and tell a cinematic story. Most important, any student of the craft can learn and lift a lot by watching these movies.

Torn Curtain, starring Paul Newman and Julie Andrews, is a cold war story of how US Physicist Dr. Michael Armstrong seemingly defects to the USSR surprising his fiance Sarah Sherman only to reveal to her he’s a US agent on a mission to get a critical nuclear formula. Once he has it, he and Sarah have to find a way back to the west.

Curtain is where most Hitchcock folks mark the end of the master’s greatness. Hitchcock fell out with composer Bernard Hermann when he threw out Hermann’s already composed score in favor of a jazzier approach the studio pushed on him. Hitch lost his cinematographer Robert Burks who had worked with the director since Strangers on a Train. The stars Hitchcock had relied on to power his movies had aged or retired. And Hitchcock found himself in the middle of an ever changing industry that didn’t know what to do with him (even though he had produced three of Hollywood’s greatest hits-North by Northwest, Psycho, and The Birds in the last 7 years).

The movie itself is enjoyable and brisk. While it doesn’t hit the heights or stay at the consistent level of genius we’d been spoiled with, it is nevertheless a total entertainment with a number of exciting sequences. In fact, the brutal killing of the bodyguard/East German henchman Gromek by Newman and a Farmer’s Wife is one of Hitchcock’s great sequences. Curtain feels like Hitchcock’s own response to James Bond and the more comic book approach to the Cold War that could sometimes dominate Western cinema. Here, the filmmaker shows you how awful it is to kill another human being. Even if you have to do it for your own self-preservation (as Newman and the Farmer’s Wife have to, to protect their identities as Western spies), there’ s no joy in it. The sequence is a masterclass in editing, shot selection, subjective POV storytelling, and emotion. It runs approximately 8 minutes and 8 seconds. Imagine any modern movie spending that much time on the killing of one person. Usually hundreds die in seconds, offscreen, just so our heroes can stop the cosmic bad guys before they destroy the WHOLE CITY or planet. And we feel little. Here, one man is killed, it takes almost half a reel, and we feel it all.

The problem is that this sequence happens before the midpoint of the movie. Every sequence after, though imaginative, full of ideas, engaging, never matches this early scene.

Still, you can learn a hell of a lot from Torn Curtain. So many Hitchcock filmmaking lessons are on tap here. In the scene where Newman defects, we see much of it from Julie Andrew’s point of view behind the scrum of journalists (Hitchcock POV shot selection, storytelling). When Andrews and Newman work to flee East Germany, the sequences are each powered by a creative idea and get shorter and shorter (fighting the cliche, embracing an organizing creative idea, increasing pace/tension without fatiguing the audience). And as one audience member said, even a good (if not great) Hitchcock movie is better than most of everything else made around that time.

We skip over Hitchcock’s 1968 Topaz (another Cold War thriller with a Cuban-Fidel Castro angle) which even Hitch felt was constrained by studio demands and lacked his usual passion and flair. It has its advocates/partisans who consider it overlooked so please check it out.

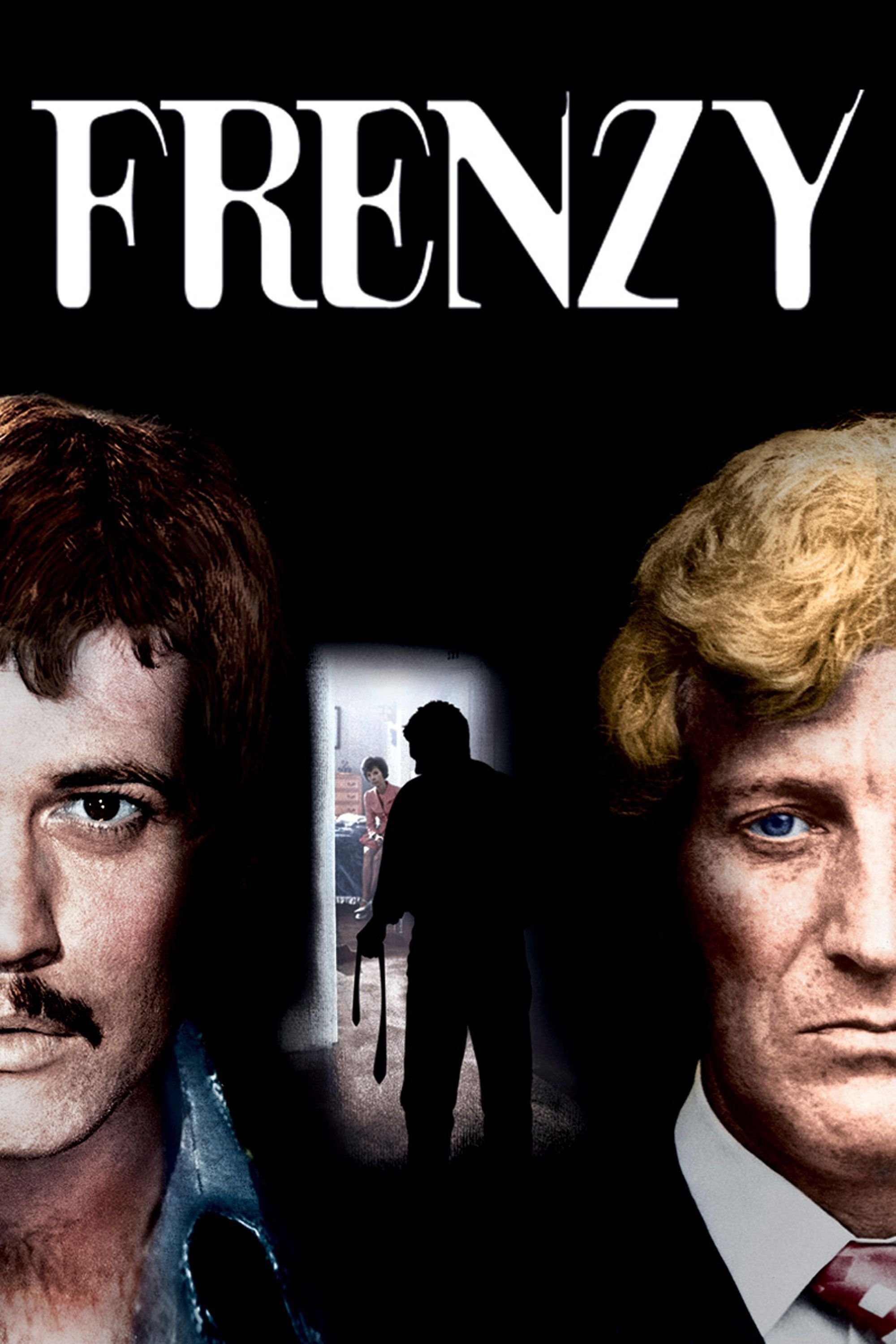

We move straight to 1972’s Frenzy which was a huge hit, found Hitchcock leaning into the new cinematic freedoms (violence, nudity) denied him in the past, and offers a real masterclass in many of the director’s most succesful techniques. Frenzy is also immaculately structured from start to finish. Here we see the combination of two of Hitchcock’s favorite suspense subgenres: the innocent man on the run who must clear his own name (The 39 Steps, North By Northwest, Saboteur) and the killer as a central character (Shadow of a Doubt, Strangers on a Train, Psycho). It probably says something that Hitchcock combined these two genres. He must have sensed he needed a hit and would use every tool in the bag to make one.

Though Frenzy never quite rings the bell nor has the felicity of a 39 Steps or a Psycho, it nevertheless is a breathless, exciting, unrelenting nightmare that only releases the tension in the very last minute. It is a GREAT Hitchcock film even at the same time that it is a problematic one. Frenzy tells the story of how tempermental bartender Robert Blaney, through horrible happenstance, comes to be the prime suspect as the “necktie murderer”, though it is really his friend Bob Rusk committing the murders. The tone of the movie is hard to explain as it is simultaneously nightmarish like Hitchcock’s 1958 The Wrong Man yet full of dark comedy like Psycho and Strangers on a Train. That Hitch manages to pull off the dual tones the entire picture is a marvel.

Frenzy also reminds us that Hitch was always best served (as any moviemaker is) with a great screenplay. Anthony Schaeffer who wrote The Wicker Man and would later write Amadeus seems to get what makes a Hitchcock movie, a Hitchcock movie, while delivering a level of thematic strength that strengthens the picture.

Frenzy, along with Shadow of a Doubt and Strangers on a Train, is one of Hitch’s great pictures using his doppleganger/twinning device of showing how the protagonist and the antagonist are in many ways strange siblings. While we empathize with Blaney, we also note that his temper and impulsiveness lead to violent outbursts. While we abhor and are even repulsed by the evil in Rusk, we note he has a fastidiousness and self-control Blaney lacks. While Blaney seems unable to escape suspicion, Hitchcock perversely delivers a sequence where murderer Rusk eludes suspicion by succesfully retrieving an incriminating piece of evidence. We find ourselves wanting Rusk to be caught yet watching the grammar of a movie scene where normally we would root for the “cat thief” or good guy to succeed and get away. Akira Kurosawa and David Lynch are two other cinematic masters to make full use of the twinning/doppleganger device the way Hitchcock does.

Frenzy also is a masterlclass in how a first act needs to give you ALL the information so the third act pays off. Billy Wilder often said “If you have a problem in the third act, the real problem is in the first act.” The third act of Frenzy is fascinating BECAUSE the first act has been meticulously executed (pardon the pun).

Finally Frenzy makes the most of how a visual motif gains power through repetition and variation. Here, the motif of horrific acts being committed or discovered BEHIND closed doors recurs in at least three key spots. After Rusk murders Blaney’s ex-wife, Hitch keeps the camera on the street outside her office so that when her co-worker arrives, we have to wait (on the street) before we hear her scream. Then when Rusk kills Blaney’s current girlfriend, the camera leaves the apartment as she enters it and goes out onto the street again where we are consumed by unsuspecting street noise. Finally, in an ingenious inversion, when Blaney is WRONGFULLY convicted of the murders in a British court, we are left outside in a hallway as the verdict is read in the court.

Frenzy does make us uncomfortable with the misogyny of the killings (all women, all sexual). Michael Caine turned down the part because he thought it was offensive (though he would later play a kind of confused sexual killer in De Palma’s Hitchcock riff Dressed to Kill). Also, the movie does occasionally elicit wonder more because it has the precision of a swiss watch then mind blowing genius. But none of this is to take away from what FRENZY is which is a great Hitchcock film.

This leads us to Hitchcock’s final feature bow, 1976’s Family Plot: a revelation if you’ve never seen it. Whereas Frenzy found Hitch making sure he had a great movie by reaching into his bag of well-tested tricks, Family Plot finds Hitch stretching his range with a great dual story suspense comedy about two pairs of thieves/charlatans/lovers whose stories converge at the climax. A structure and a movie that is new for Hitch.

Hitch had seen Altman’s Nashville and had been greatly impressed both with one of its lead actresses (Barbara Harris who stars here as a good hearted but goldigging fake “psychic”) and its tapestry like way of storytelling. Working to show he could make a mid-70’s movie with the best of the young Turks, Hitch and collaborator writer Ernest Lehman (North by Northwest) wrote a great movie where we see two couples actively working against each other and getting closer and closer to a confrontation without realizing the connection of the other couple. There’s a giddy American 70’s cinema vibe to watching Harris and her lover-good natured if somewhat always frustrated cabbie/detective Bruce Dern try to find a long lost heir to a family fortune so they can claim a “finder’s fee” while William Devane and 60’s/70’s indie queen Karen Black (often disguised in a blonde wig and black trenchcoat-a look De Palma would lift for Dressed to Kill) blackmail and kidnap and hide jewels in their chandelier. Devane and Black also hold the key/answer to the Harris/Dern mystery.

By the time these two couples converge at Devane and Black’s home (complete with a secret hostage room that becomes the scene of one of the great moments in the climax), we’ve been treated to a buffet of delights. Supposedly Lehman wanted to lean into the dark aspects of the story but was constantly encouraged to lean the other way and emphasize the light heartedness and comedy by Hitchcock. There’s a kind of joy in the movie that is a welcome reprieve from the dark brooding of Frenzy.

Ironically, it may have been this light heartedness that kept Hitchcock lovers and film critics from fully realizing what a joyful final bow Family Plot truly is. If not a masterpiece, the movie at least shows that into his mid-70’s, Hitchcock wanted to push himself and explore the greatness of an idea that would grab him (here telling two seemingly unrelated stories that converge into a very connected single story in the final scene). Family Plot shows that Hitch understood greatness lies in pushing oneself and one’s limits and trying for something original and new. And, as with so many movies by the master, it is consummate and entertaining. From the start to the end of his career, Hitchcock held to a golden rule few filmmakers observe consistently: he was never boring. He was always restless.

Craig Hammill is the founder.programmer of Secret Movie Club.