Lars Von Trier's DOGVILLE: When Provocation succeeds in cinema by Craig Hammill

Lars Von Trier’s 2003 DOGVILLE comes at a fascinating point in Von Trier’s overall filmography. Made when the moviemaker still professed (at least in interviews) that he continued to have faith in God (and was a practicing Catholic) but before his very public (to this day) announcement that age and experience had converted him to atheism, DOGVILLE represents one of the world’s most talented moviemakers making both a provocation and an interrogation into human nature and the nature of the divine-at least as we’ve come to understand it in the Judeo-Christian tradition. DOGVILLE is easily one of Von Trier’s best movies and it may be the conflict within himself that elevates it to the top tier of his work.

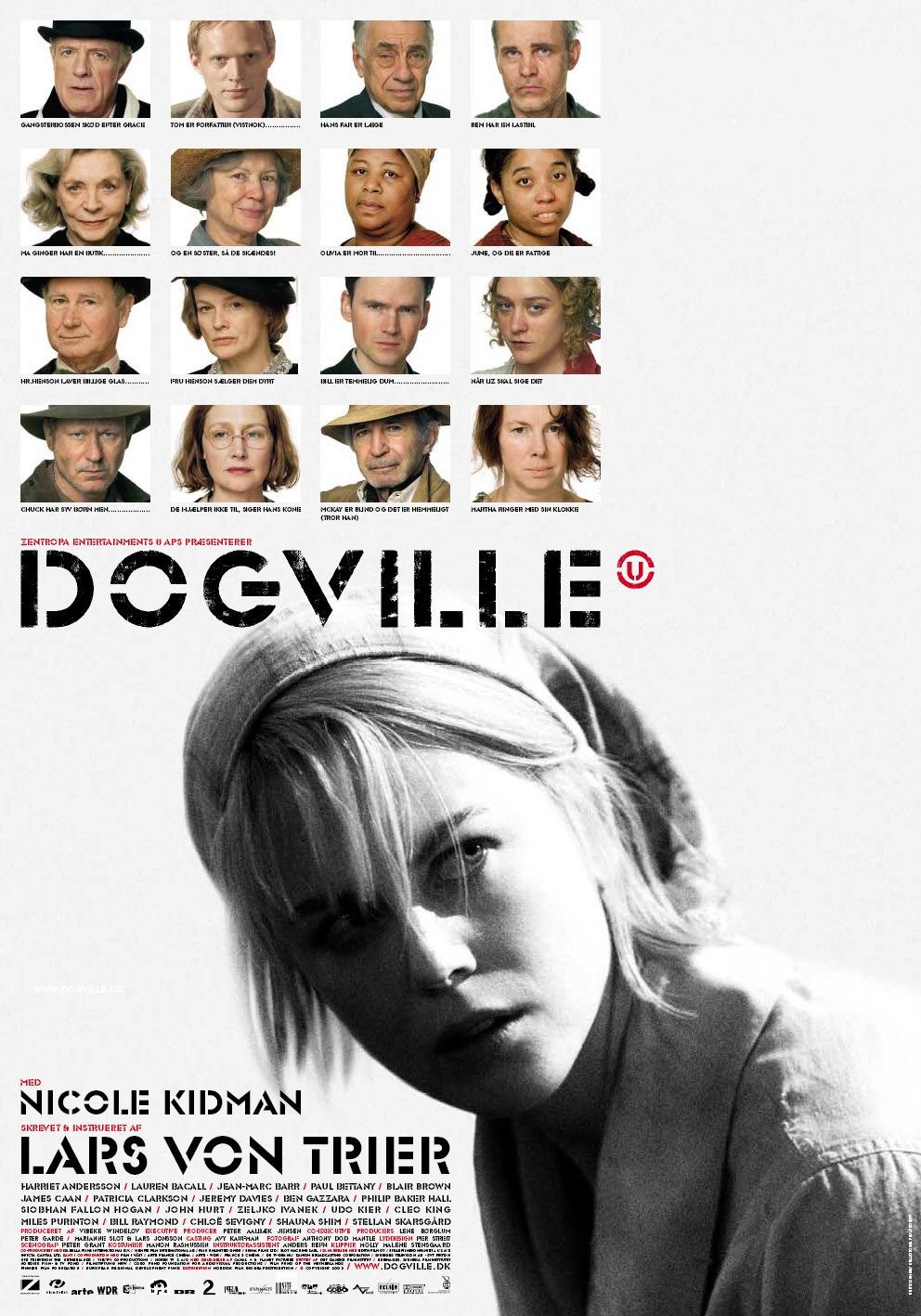

The movie tells the story of mysterious fugitive Grace (Nicole Kidman) who arrives on the run in the small Colorado town of Dogville. Local intellectual Tom (Paul Bettany) convinces the hesitant townsfolk to hide Grace from brutal gangsters searching for her. At first Grace’s presence seems to bring out the best in everyone. But then, bit by bit, it clearly brings out the worst. Ultimately the townspeople use Grace’s kindness and her desire to hide, against her. They exploit and abuse her before finally trying to claim the large reward offered by the gangsters through turning her in. The results are not what anyone expected.

DOGVILLE is made in an intentionally provocative style: it is shot on a large soundstage with only minimal suggestions of sets, props, etc. Most of the town is marked off in paint and titles (“MA GINGER’S SHOP, etc) on the floor like a map. The movie is narrated by John Hurt with dry irony. This writer was somewhat aware of the influence of modernist German playwright Bertolt Brecht (whose many masterpieces often broke the fourth wall and made the audience aware they were watching a play) the first viewing. This viewing, the influence of Stanley Kubrick’s BARRY LYNDON also became palpable. From the ironic chapter headings to the classical music score used as counterpoint, to the omniscient narrator, DOGVILLE has a wonderful cinematic-novelistic hybrid feel.

As with Von Trier’s best provocations (of which I’d include Breaking the Waves, the Kingdom TV series, Melancholia, and The House That Jack Built, the conceit is NOT just to be shocking for shocking’s sake. It becomes an exciting high wire tight rope act where Von Trier’s aim appears to be to get us totally engrossed in a story while stripping himself of all the filmic tools that normally allow a filmmaker to create such engrossment.

Von Trier also (as he always does) knows when to break those rules. And there are beautiful moments, shots, scenes of cinematic heft and beauty. Summer danders float by the thousands in one sequence. There are many God’s eye view shots from above the performers (a thematic hint at what’s coming by the end). And there’s even a disturbing extended sequence where Grace tries to run away by paying the local truck driver to smuggle her out of the town. We see Grace through a transparent double exposure of the burlap cover that hides her amongst apples in the truck. This double exposure creates a striking beautiful, cinematic image.

This approach by Von Trier-to punctuate one dominate style with moments (or endings) of operatic cinematic beauty has often worked more times than it doesn’t. Jack’s final Dante like trip through hell in The House That Jack Built (2018) grabs us because the rest of the movie has been shot in a mostly handheld naturalistic style.

The stripped down theatrical approach in Dogville puts increased attention on performance. And for the most part, Von Trier gets amazing performances out of his stacked cast which includes Kidman, Bettany, Ben Gazarra, Patricia Clarkson, Stellan Skaarsgard, Chloe Sevigny, Lauren Bacall, James Caan to name just a few. It bears noting here that all the performers (including the children) commit to Von Trier’s formalistic precepts heroically. Not once do you feel (from any performer) a discomfort or nervousness about the strange hybrid theatrical-cinematic approach.

But if Von Trier were just a taunting, teasing, iconoclastic stylist, the movie would not be as powerful as it is. Von Trier, like Ingmar Bergman and Stanley Kubrick, knows a large part of the power of a movie is in its ideas.

So why does Von Trier tell this story with this style? As with all great movies and great moviemakers, this writer feels it’s a fool’s errand to speak declaratively on such things. Great movies like great music are collaborations produced, forged, and honed in a furnace of intuitive creativity that transcend (or at least necessarily defy) analysis. If words could fully explain movies, we’d just need film reviews, not the films themselves.

Still, seeing DOGVILLE a second or third time does allow you to move past the bold style to focus on the themes. And the themes are fascinating even if, ultimately, this writer doesn’t agree with the thematic implied conclusions.

For much of DOGVIILLE’s runtime, the clear theme seems to be the brittleness of human nature and the fragility of altruism. Grace is truly good. She is giving, charitable, loving, trusting, humble, patient. That the Townsfolk at first seem improved by that goodness before descending into awful behavior seems to be a comment on the innate selfishness at the root of much human behavior. We all talk about wanting to do the right thing and change for the better. But we often tend to act out of impulse, self-need, and emotion.

It’s painful to have to confront such themes. Because while Von Trier (especially in DOGVILLE and his later work) seems to give up more and more on human nature, a cinematic challenge to us the viewers doesn’t mean we have to give up on it. But it does keep us sharp to confront and wrestle with such truths.

But the full breadth of Von Trier’s thematic ambition becomes clear when the gangsters return at the end. For we learn (and may have always suspected) that Grace is the daughter of the lead gangster (James Caan). And that she fled from him because she wanted to be good and not be near the violent power he wields.

The final conversation/debate between Grace and her Father (in his luxury car) appears to be that between Jesus/New Testament forgiveness/mercy and the Old Testament God who judged, punished, obliterated weak humans for transgression.

And Von Trier does successfully provoke us in the debate. Do the people of DOGVILLE deserve forgiveness and mercy? We’ve seen them exploit, rape, and imprison Grace. And it’s not far fetched to think that ultimately down the line they might have even have killed her and hidden her body. At first Grace thinks they are still deserving of forgiveness but her Father points out her attitude is as arrogant as the attitude Grace hates in her parent. Grace is saying she (Jesus) can be merciful and forgiving but she doesn’t expect it from anyone else and they can be awful. Thus Grace is de facto saying she is better than those around her. She is not holding them to the same standard.

It’s a fascinating, powerful point to ponder.

Nevertheless, the end of the movie finds Grace deciding the world is truly better off without DOGVILLE and she orders every person killed (including the children) and the entire town burned to the ground while her Father watches admiringly (very Old Testament).

While I love this ending from a daring, ambitious, shocking purely cinematic point of view, I don’t agree with it thematically or with its implied conclusions. It is not true that every person in DOGVILLE was equally awful. And it’s also not true that mass murder somehow is a just punishment for the sins and transgressions of the town. And it’s also the point of mercy and forgiveness that such ideals, while hard, and often untenable in the world we live, can produce outcomes of peace, love, understanding, reconciliation, and, yes, Grace.

At least in this writer’s opinion.

But whether you agree or disagree with Von Trier’s ultimate thesis and idea, you are thrilled by the ambition of his intent. And if he gets a conversation going, he has accomplished one of the pinnacles of what cinema can do.

And this is ultimately this writer’s feeling about DOGVILLE. While this writer is in conflict with DOGVILLE’S conclusions and feels, fundamentally, different (a conversation for another time), this writer admires the daring, ambition, scope of the movie. DOGVILLE is a proof of what cinema can do. What cinema can still do. And when something provokes, it doesn’t mean you have to agree with it. But it does mean you have to honestly wrestle with it and come to your own conclusions.

Von Trier at his best has always strived to create such cinema. This is cinema in the tradition of the ambition of Carl Theoder Dryer, Akira Kurosawa, Jean Renoir, Ingmar Bergman, Stanley Kubrick, Robert Bresson, Andrei Tarkovsky, Fellini, Goddard, Fassbinder, Satyajit Ray, David Lynch, and many other moviemakers who are true believers in the magic and potential of the art form.

And anytime a moviemaker evokes that sense of awe in the audience, it is a good thing.

Craig Hammill is the founder.programmer of Secret Movie Club.