Late Period Scorsese: The era of mining complex emotions by Craig Hammill

It’s fascinating to watch a director like Martin Scorsese enter a new period late in his career. 2016’s Silence, 2019’s The Irishman, and 2023’s Killers of the Flower Moon all feel part of a new Scorsese focus. A period where Scorsese devotes all his energies to mining a complex emotion through a stripped down focused style.

Gone are a lot of the flashy camera moves, music cues, and edits of previous eras. Instead Scorsese, collaborating with cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto and long-time editor Thelma Schoonmaker, focuses on “essential cinema”.

You might call this Scorsese’s Mizoguchi period. Scorsese is an avowed fan of Japanese master moviemaker Kenji Mizoguchi’s 1953 movie Ugetsu about two farmers who abandon their families to try their hands at the fortunes of war only to realize too late what they’ve sacrificed. These most recent three Scorsese movies all revolve intensely around themes that Scorsese has explored his whole career: spirituality, faith, the toll of surviving in the secular world. But now these themes have the kind of urgency and examination attendant to someone who knows that each new movie is a kind of summing up of a lifetime of existence.

I went to go see Killers of the Flower Moon fully expecting a handsome if flawed and overlong movie. Killers is all of those things. But I was surprised at how much I truly liked and was moved by the movie. I wasn’t fully prepared for just how intensely Scorsese, through the amazing performances of Lily Gladstone, Leonardo Di Caprio, and Robert De Niro, would look at humanity’s endless capacity to rationalize and lie to itself.

For anyone who hasn’t seen the movie, it tells the real story (based on David Grann’s true-crime bestseller) of how the indigenous Osage tribes of Oklahoma were relegated to what was thought of as “worthless” reservation land only to discover oil and become the richest people for a time on the planet. And how white American society disregarded the dignity and humanity of the Osage and embarked on a murderous campaign to get all the money until the FBI stepped in (after having been paid $20,000 by the Osage themselves to solve the murders).

While the movie is far from perfect, the central relationship of Osage Molly Burkhardt (Gladstone) and her white none-too-bright scheming husband Ernest (Di Caprio) is fascinating. They clearly love each other and are clearly building a family together. At the same time, Ernest, under the thumb of his murderous Uncle Bill “King” Hale (De Niro), is killing off Molly’s family to get closer to the rights to her oil. Even the scheming Hale presents himself as (and maybe even believes himself to be) a true friend to the Osage.

It’s a disturbing and fascinating picture full of complex and contradictory scenes. It’s clear EVERYONE is lying to themselves. Not just Ernest and Hale but Molly herself who wants to believe her husband has her best interests at heart despite mounting evidence until the very end when it’s impossible to ignore the consequences and dangers of his actions.

What’s so essential about Killers is how it gets at the dark heart of all of our dark hearts. Most of us are the “heroes” of our own narratives even if we’re doing countless things that harm, ignore, hurt others and don’t really help our own lives.

Killers has noticeable flaws. It’s not clear that it needed to be three and a half hours (one feels the movie could have lost an hour and maybe had an even more concentrated impact). Its third act plays (strangely) like an early 20th century re-hash of the third acts structurally of Goodfellas and The Wolf Of Wall Street (the main character gets caught by law enforcement and strikes a plea deal). One feels that Scorsese may have chosen that structure because he’s comfortable with it. And the movie doesn’t necessarily benefit from the re-use.

But then again, this writer is no Scorsese and maybe the movie wouldn’t have had the intensity and impact it has if it didn’t have the runtime. One does come away from the movie feeling like Scorsese has made his Elia Kazan 1950’s-1960’s epic. Movies like East of Eden, Wild River, and Giant (directed by another amazing moviemaker George Stevens) all come to mind when watching Killers. It is working to be (and mostly successful in its goal) one of those great mid-20th century Hollywood movie epics.

The Irishman, a three and a half hour gangster elegy, about the real life claim by Teamsters Union sub-boss and mafia hitman Frank Sheeran (played by Robert De Niro) that he murdered his best friend and Teamsters boss Jimmy Hoffa, ultimately focuses on how a lifetime of survival decisions can cost someone their family (even if at the same time they were trying to provide for their family). The Irishman dispenses with much of the style pyrotechnics of Goodfellas, Mean Streets, Casino, The Departed in favor of zeroing in on the point that even a killer like Sheeran could, very plausibly, have been sane, rational, loving to his family, torn up by things he did. The movie becomes a metaphor for any of us taking stock of the decisions we made in our lives to survive and the consequences of those decisions.

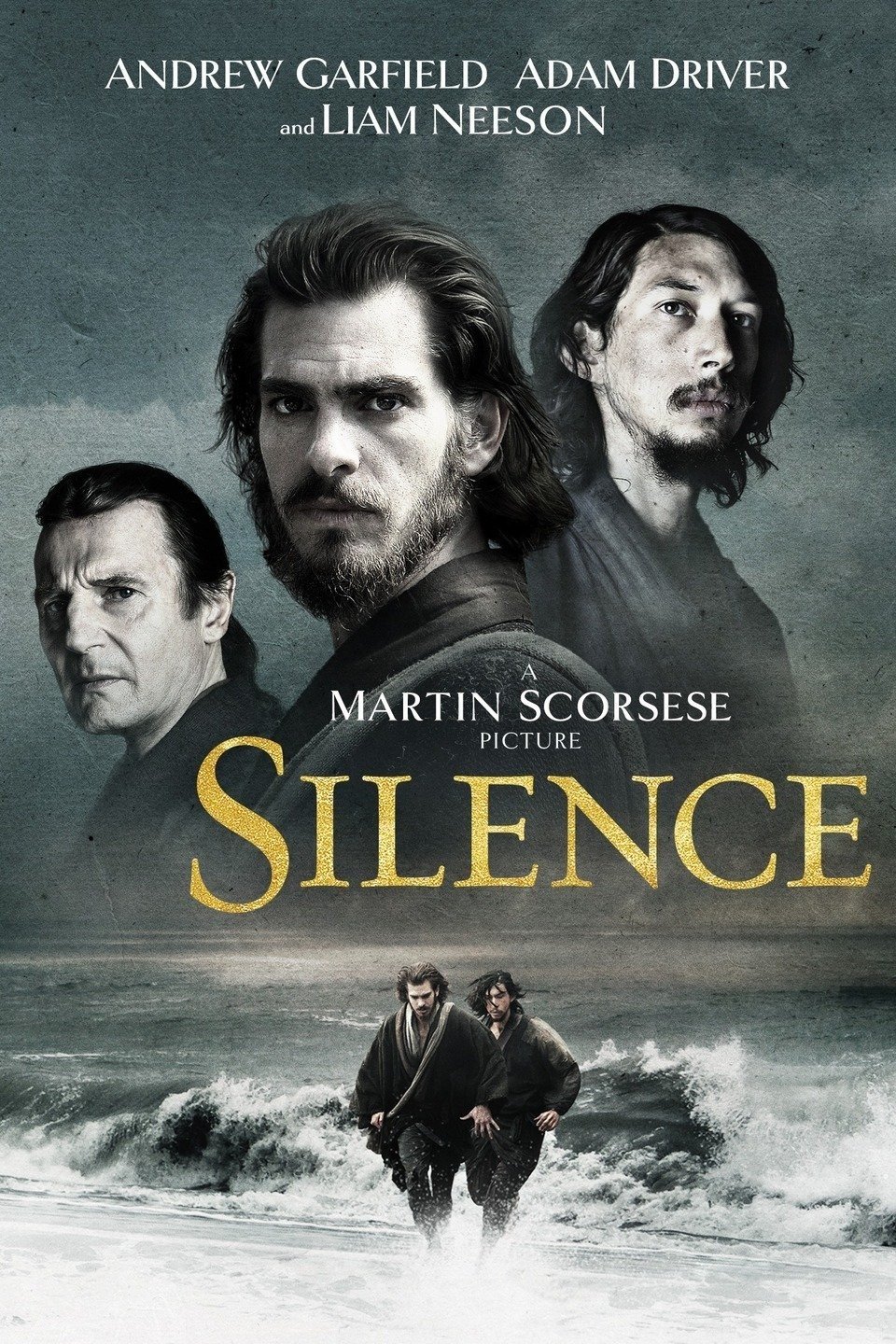

Silence, based on Japanese Catholic author Shusaku Endo’s brilliant novel, follows two Catholic priests’ secret mission to find out what has become of their hero and mentor Father Rodriguez in a 17th century Japan that has decided it wants NO foreign religion. After rewatching the picture a second time, this writer noticed that the ending may be read several ways. Scorsese, who has openly discussed in recent years his own spiritual struggles and doubts in later age though he still retains a belief in God, may be affirming his belief in faith itself rather than affirming a belief in God. It’s a fascinating message if Scorsese is ultimately saying “I don’t know if God exists but I believe a faith in God is powerful, important, admirable.”

This writer remembers reading Goethe’s Faust Parts I & II. Part I was written in Goethe’s relative youth. Part II in Goethe’s older age. Part I was one of the great works of literary art this writer has ever read. Part II seemed very detached, meandering, philosophical, and aloof. But as this writer ages, it becomes clear that older, late period works often focus on elemental summational concerns not obvious to us in youths gripped by the hurly burly impulses of lust, ambition, emotion.

While I do mourn on occasion the loss of Scorsese’s incandescent experimentation with film technique, the vital creativity that has made so many of his movies exhilarations, I do thrill at the tremendous pursuit of truth, revelation, and observation infused in these later works. Ultimately it’s not that one approach is better than the other. It feels more that we should be grateful that a film artist like Scorsese is dynamic and daring enough to commit to different focuses in different periods. And that each period, always marked by Scorsese’s full commitment to cinema and craft, is a gift to all who love movies.

Scorsese proves that cinema can be anything if moviemakers have the commitment and passion to always search and try new ways of expressing vision.

Craig Hammill is the founder.programmer of Secret Movie Club