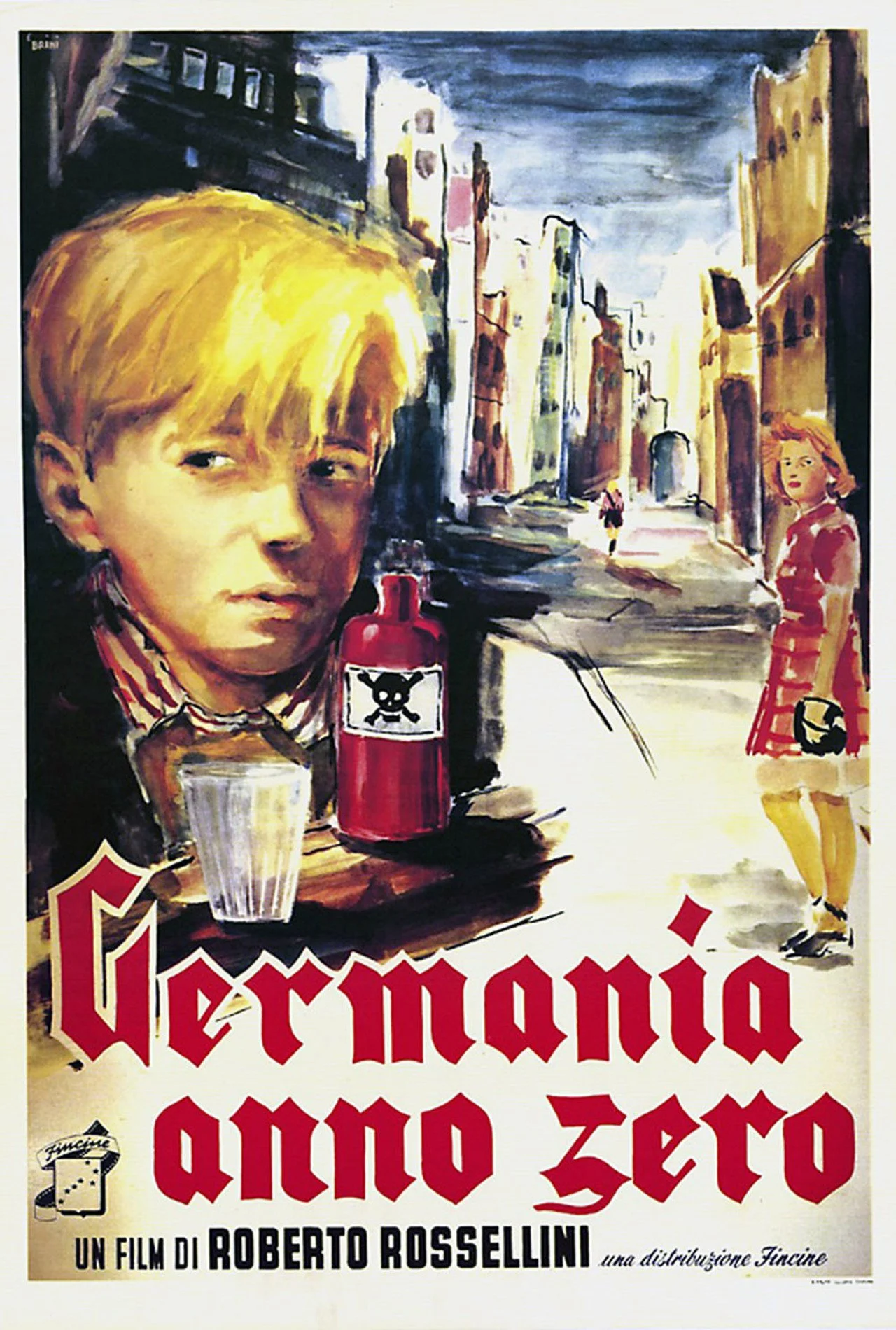

ROSSELLINI'S WAR TRILOGY (Part 3 of 3): Germany Year Zero (1948, co-wri & dir by Roberto Rossellini, France/West Germany/Italy, 78 mns)

This blog is part 3 of a three part series on Italian moviemaker Roberto Rosselini’s famous World War II trilogy-Rome, Open City (1945), Paisan (1946), and Germany Year Zero (1948).

It should not be a shock that Germany Year Zero is the most brutal Rossellini movie of his War World II trilogy.

Despite having watched a woman gunned down in the street, a man tortured to death, and a priest executed in Rome, Open City, despite having seen two budding lovers killed and then entire families executed in Paisan, the experience of watching the brutal, unsentimental Germany Year Zero still grabs you.

Roberto Rossellini’s Germany Year Zero follows young German boy, Edmund, as he wanders a bombed out post World War II Berlin, trying to find ways to help his struggling family. As so many similar families struggle in the immediate aftermath of the war. Edmund’s father is sick and ailing in bed. His older brother, Karl-Heinz, a German soldier, hides from the police and refuses to help the family for fear of being arrested. His sister Eva flirts with the boundaries of being a call girl, escort, girlfriend to get money, cigarettes, resources for the family.

The movie continues Rossellini’s commitment to showing things movies were not supposed to show. The five or six families that all share the same apartment are mean and petty to each other. Edmund encounters a former school teacher who is clearly a pedophile who procures young teenage boys for another pedophile. Edmund’s friends, if you can call them that, include a barely adolescent girl who seems okay trading sex for the meanest of attentions from other street boys.

You know this will be a rough ride when the opening scene is of Germans digging graves for money who chase away Edmund because they see him as competition.

Germany Year Zero goes beyond being brutal and ends up despairing. But how could it be anything else? These experiences and scenes almost certainly did happen in the immediate post-war aftermath.

The movie is a masterpiece.

Rossellini had just lost a son, Romano, to appendicitis. He dedicates the movie to his memory. And in interviews, Rossellini stated that he cast teenage circus acrobat Edmund Moeschke as young Edmund because of his similar appearance to his own son.

Now what does that mean? It’s hard to even parse out. Why would you make such a bleak movie with the lead acting as a kind of surrogate for your just deceased son and then put that surrogate narratively through unspeakable horrors.

The movie almost feels like a proto Lars Von Trier movie a la The Idiots or Dancer in the Dark in that our lead goes through ever increasing miseries yet feels almost angelic.

As hard as the movie is to bear, it becomes even more unbearable in its final twenty minutes. Edmund makes a misguided gut-wrenching choice with dire consequences. We won’t spoil it here as, in many ways, it is what the movie is all about. But it’s such a shocking decision that you wrestle with it.

It’s also clear once you watch all three movies in the trilogy that Rossellini, like a lot of Europeans, has a lot of fury at the Germans. Here, in Germany Year Zero, Rossellini almost seems to be trying to make a movie as an act of forgiveness. He knows the regular Germans are suffering as much as anyone. He shows it. The director has compassion. . .real love for Edmund, Eva, Karl-Heinz, and their father. Rossellini observes the daily struggles of the Germans and sees the iniquity in it.

And still, we get several characters, like the Nazi pedophile school teacher, who echo similar portrayals of Nazis in Rossellini’s Rome, Open City. That is to say portrayals so one dimensionally evil they border on being caricatures.

But when the entire world has had to suffer at the hands of a destructive, elitist, psychotic ethos can you blame the injured for not being magnanimous?

The power of the movie, and it is a powerful movie, lies in its central truth. How can you expect children to function in the world when all the adults around them have been weak, petty, or psychotic?

Edmund never has a real chance because the people he holds the most dear have let him down. His father has a clear eyed view of what’s going on but his physical sickness mirrors his decades long moral weakness. The father says “we had a chance to stop them (the Nazis) and we did nothing”. Edmund’s brother bought into the Nazi lie and fought as a German soldier. Now he hides in cowardice. Edmund’s teacher, who Edmund naturally would be inclined to trust, is a terrified ex-nazi who still finds time to paw sexually at children. And in fact, it is something this teacher says that causes Edmund to make a horrible decision.

Edmund wanders a bombed out, rubble strewn apocalyptic Berlin landscape. It just as well could serve as a metaphor for his inner state.

There is a rigor and anger to Germany Year Zero that feels like Italian neorealism as sharpened razor. As a vise we have to put our head in. The movie reminds you-oh yeah, this is what movies can be when the moviemakers have the craft, anger, work ethic, and genius to put all the elements into the imperfect furnace of movie creation and somehow use the pressure to create a diamond.

Late in the movie, in the depths of existential terror, Edmund stumbles upon a church organist playing a hymn in a bombed out cathedral. Other passers-by, suffering their own traumas, all stop and listen. It is an amazing moment. And then everyone moves on.

Now at the end of the World War II neorealist trilogy, it is clear why these movies inspire so many. Even almost eighty years later, there is something naked, intense, daring about these works. Of course they would inspire a Scorsese, a Kazan, an Ingrid Bergman. Movies up until that time had mostly still bought into the notion that movies should entertain. If they were daring or topical, they would still find a way to stumble into a happy ending or provide enough theatrical artifice to make the suffering depicted palatable. A dose of sugar to make the medicine go down.

There are no doses of sugar in these movies. There are moments of grace. Which also happen in real life. But those moments co-exist with horror.

Craig Hammill is the founder.programmer of Secret Movie Club.