ROSSELLINI'S WAR TRILOGY (Part 2 of 3): Paisan (1946, co-wri & dir by Roberto Rossellini, co-wri by Federico Fellini, Italy, 126 mns)

This blog is part 2 of a three part series on Italian moviemaker Roberto Rosselini’s famous World War II trilogy-Rome, Open City (1945), Paisan (1946), and Germany Year Zero (1948).

Paisan continues the bold and shocking rhythms of Rossellini’s Rome, Open City. That is to say the movie is at turns humanist, observant, romantic, serene, funny, brutal, violent, unbearable. Like Jean Renoir in France, Rossellini is a gambler of tone. He seems to understand intrinsically, as Renoir did, that life is NOT one genre. One emotion. One “vibe”. It is instead a horrific sublime cacaphony.

Again co-written by a young Federico Fellini, Paisan is a natural progression, sequel to Rome, Open City. Where the first movie dealt with the German occupation of Rome during World War II, Paisan tells the story, in six connected but discrete episodes, of Italy’s liberation by the Allied forces in 1944.

The movie has the narrative progression of the liberation itself. The first story starts in the south on the island of Sicily, where American forces first landed to move northward. And each successive episode takes place slightly more north than the one before. The movie charts the progression of the Allies pushing back the German line/front. By the sixth episode, we are in Italy’s northernmost regions BUT we have crossed behind enemy lines where the Germans, in late 1944, still controlled territory. So there is a progression, escalation of danger and violence, open combat as well.

Paisan refers to the Italian freedom fighters who were anti-fascist and fought the Germans alongside the Allies. Like the French freedom fighters, or really any resistance fighters in any occupied country, Paisans made bold choices with dire consequences. Anyone they came in contact with would be in immediate danger for aiding the subversives against the occupying force.

The conflict of communication between American soldiers and Italians is one of the meta-themes of the movie.

Fellini, interestingly, had issues writing about the Paisans for this very reason. And yet, he is the co-writer on two of the most powerful Italian movies about the Paisans. It was also here on Paisan that Fellini got a chance to start directing. Rossellini entrusted the young Federico with certain B-roll scenes. One senses the young Fellini’s humorous, humanist touch possibly providing a balance to Rossellini’s own drive for honesty, truth, brutal humanity. Yet Fellini himself adopted this Rossellini-esque strategy of being brutally honest AND openly loving. Both Rome, Open City and Paisan are brutal, shocking, violent movies. But they are also warm movies, a hallmark of Fellini’s great works. And the combination of brutality and emotional warmth is a shockingly effective cocktail indeed.

The six episodes ALL work. Unlike some anthology or episodic movies, the episodes have a uniformity in quality, focus, theme. While you might prefer or remember some over others, there’s not a bad or even mediocre episode in the entire movie (though a few flirt with melodrama).

The episodes progress also on themes of love, relationships, understanding amid war until the shocking final episode which we’ll get to in just a moment.

Before that harsh climax, we see American GI’s haltingly trying to talk to local Sicilian girls, an African American MP realizing just how poor a young street thief is, an Italian call girl meeting an American soldier who knew her before she resorted to prostitution, a British nurse daring a trip to war torn Florence to find a former love turned Paisan, a Jewish, Protestant, and Catholic trio of Chaplins spending the night in a monastery with Catholic Franciscan monks (who also turn out to be anti-Semitic and anti-Protestant). . .

This penultimate episode is also the movie’s most quietly comical and it ends on a strange ironic note of both grace and gridlock. Of irresolution.

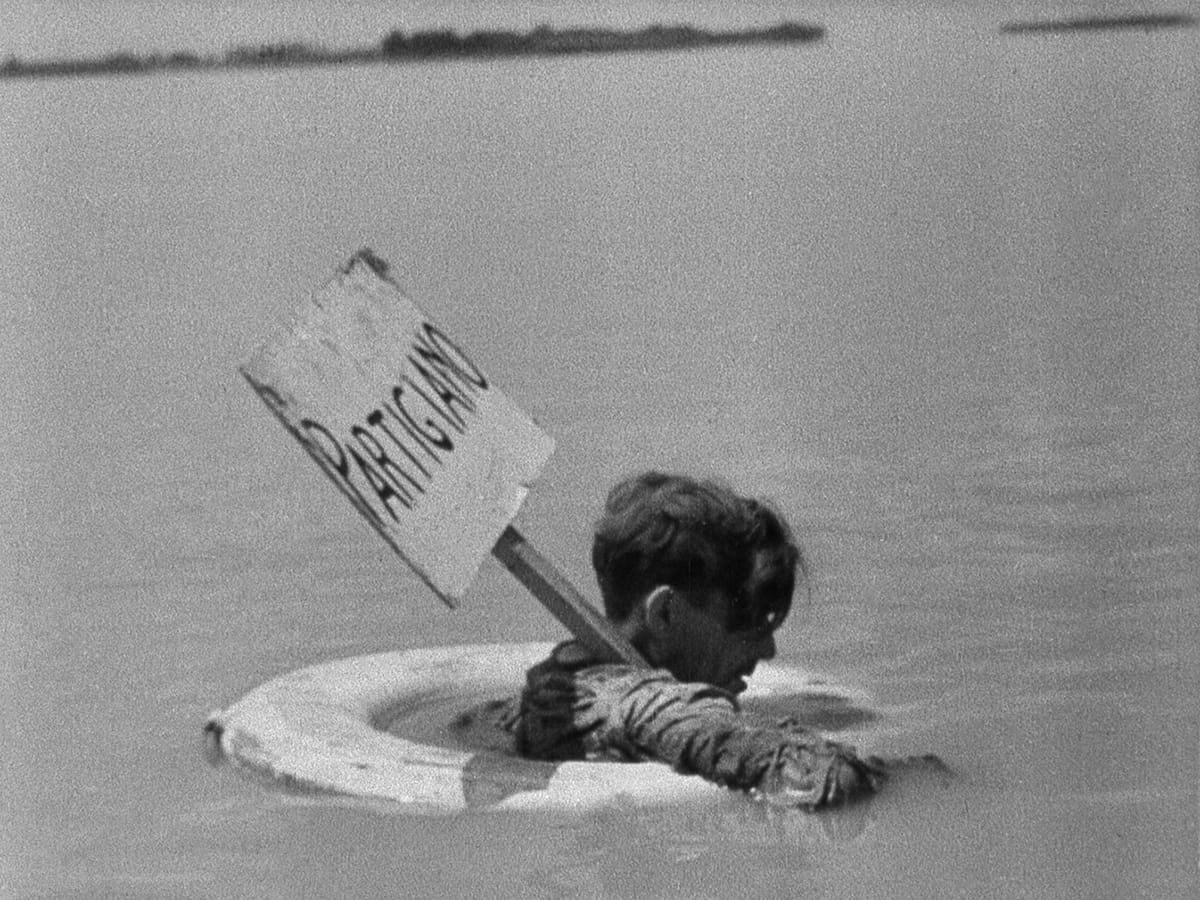

And then. . .we get the final episode which opens on a famous shot of a dead Paisan floating in the Po river with a sign calling him out as a Paisan. In the eyes of the Germans, a traitor.

Paisan continues to have scenes of shocking violence and loss just as Rome, Open City did.

This final story is NOT cynical. But it is unbearably brutal. We follow Paisans and American OSS (the precursor to our CIA) surrounded by Germans. When locals help the Paisans and Americans with food, they are repaid by being executed by German soldiers for assisting the enemy. This results in an unbearable image of a toddler wailing amongst the bodies of his slain mother and father.

And the very end of this episode, which we won’t spoil here, has a very rough scene that may have been an inspiration for an equally brutal section of Martin Scorsese’s Silence. But what this final episode drives home is that Paisans WERE NOT even afforded the basic rights given captured soldiers by the Geneva convention. Captured soldiers who, under international law, had to be kept alive as POWs. The Paisans were simply viewed as “outlaws” and treated little better than rabid dogs.

And so the movie ends on a deep irony. That for the Italians, fighting for the liberation of their own country, IN their own country, there often was no reward, no liberation, no grace. In fact, the fight came with humiliation, degradation, and trauma.

Rossellini is quoted as saying that his commitment in these movies and some of his later works was to truth as best as he could film it. This in some ways might be his definition of Italian neorealism, the genre he helped define.

This commitment makes these movies stand out. Both Rome, Open City and Paisan are still shocking in their unflinching portrayal of the suffering, death, injustice, horror, compromises of war. Paisan also finds a way to comment meaningfully on things like racism, anti-semitism, poverty, survival, hypocrisy, spirituality.

There is a kind of cinematic essence in the best of the humanist moviemakers. Renoir, Ford, Fassbinder, Kurosawa, Fellini, Rossellini, Mike Leigh, Kiarostami, Hou Hsiao Hsien, among others, at their best, achieve a kind of pure cinema through the depth of their understanding of human nature. Though all these moviemakers are skilled movie craftspeople, it is their psychological insight that elevates their work to the ranks of the very best.

Paisan is occasionally melodramatic but it is not sentimental. It is a movie about the horrors of war and the occasional grace notes of triumph that still ring out. Made so close to the actual events themselves (Paisan was made just one year after the war ended), the movie has an immediacy and truth that feels like it could only have come from people who had JUST lived the experience they are now recreating. Who still had the fresh wounds and memories of exactly HOW IT WAS. This too might be at the heart of Italian neorealism. These masterpieces, made in the 1940’s and early 1950’s, are about experiences being lived daily by those who made the movies.

Rossellni never looks away. He never flinches. But he never misses an opportunity to celebrate what’s good in humanity either.

Craig Hammill is the founder.programmer of Secret Movie Club.