Peckinpah: Problems & Perfections by Craig Hammill

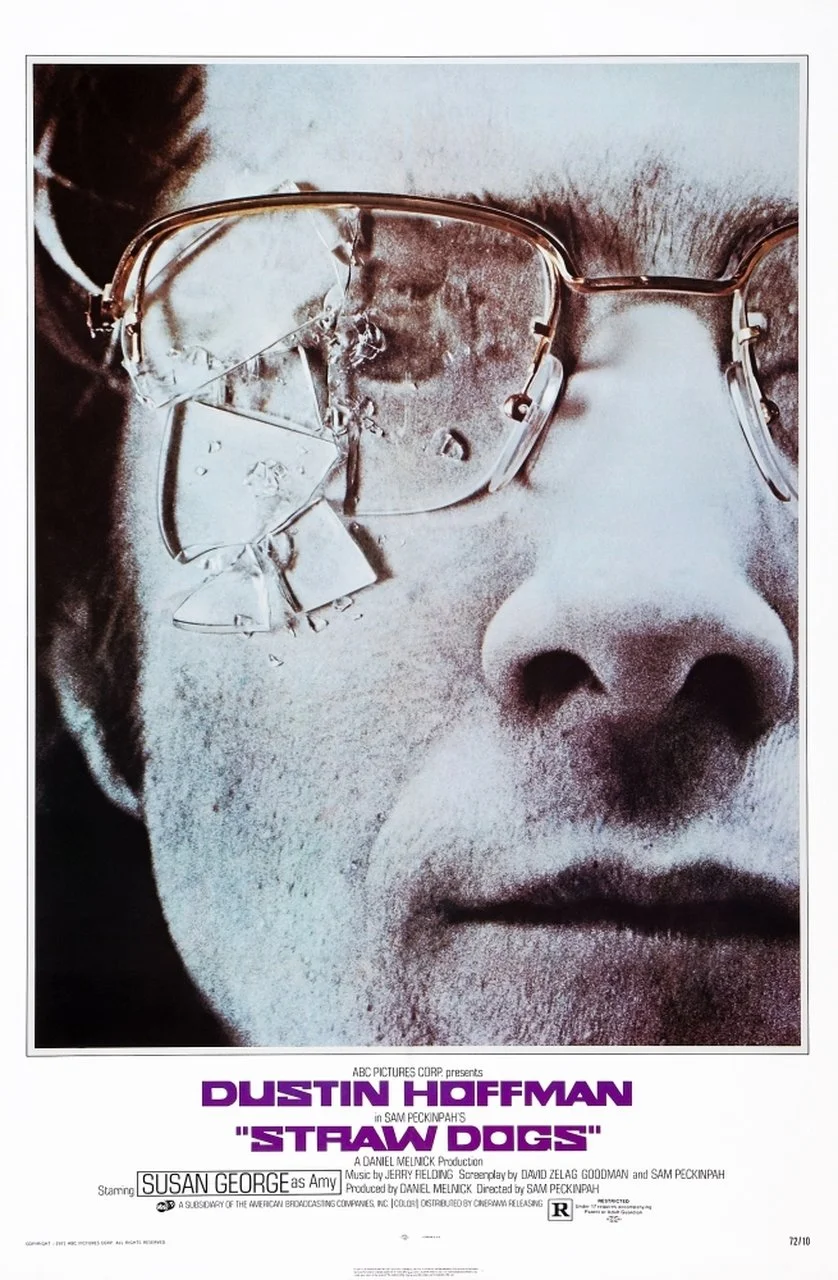

We recently screened two of mercurial filmmaker Sam Peckinpah’s greatest movies: The Wild Bunch (usually cited as his masterpiece) and the unsettling Dustin Hoffman starring home invasion movie Straw Dogs.

Watching the movies, I was struck by several things.

One-Sam Peckinpah and his editors cut some of the best edited American sequences of the last sixty years.

Two-Sam Peckinpah is a filmmaker of both problematic and perfect sequences.

Three-Peckinpah’s explorations into the nature of violence are the real deal. He’s not just a director who figured out a new way to shoot action. The violence is the point.

For anyone who has never seen a Sam Peckinpah movie, here’s a quick synopsis on the filmmaker and his work. Peckinpah grew up in the 1930’s in a rural California ranch family and the fallout from the sale of his beloved ranch (supposedly by his mother from whom he was alienated thereafter) marked him for life. He went on to enlist in the military and saw horrible acts of violence between the Japanese and Chinese during his tour in China in the 40’s/50’s. He also appears-whether as a result of PTSD or action he saw during his active service or even pre-existing mental health issues-to come back from this service a deeply troubled person. His life would be marked by increasing bouts of alcoholism, substance abuse, inability to maintain relationships, and erratic behavior. He was mentored by Don Siegel in the 1950’s and came up through television like Sidney Lumet and Paddy Chayevsky among others. After several key western TV programs and early movies marked by studio interference that still showed promise-Ride the High Country, Major Dundee-Peckinpah was allowed to make The Wild Bunch in 1969. Its violence, specifically its ending was shocking, revelatory, and revolutionary.

Moviemakers like Martin Scorsese and John Woo would develop Peckinpah’s approach of shooting violence at both multiple frame speeds into styles all their own. And countless action movies would adopt the style simply to make action sequences more dynamic (rather than to emphasize any specific story beat within the sequence).

But to this programmer, what separates Peckinpah from the visual violent action movie fetishist, is that he places an examination of violence as a key story component of his work.

Or put another way, Peckinpah knows his movies are violent and he wants to examine why that is.

What comes across clearly in The Wild Bunch is Peckinpah’s own sense of how a certain kind of masculinity has no place in the coming era. For Peckinpah, this is elegiac. For many of us looking back, this is a good thing. Peckinpah both examines and embodies a kind of destructive masculinity that not only hurts the individual but all those around that individual who must endure it.

The Wild Bunch also, however, paradoxically, makes an equally important (at least to this programmer) point that even hardened amoral outlaws discover some kind of ethical and moral center within themselves that they can’t violate without losing their souls completely.

What’s fascinating about The Wild Bunch is that we’re shown at the very beginning that William Holden, Ernest Borgnine, and the rest of their gang are willing to do almost anything to rob banks and get away (including putting a local church group in harm’s way). You can see these guys are gonna get taken out at some point. They live too recklessly with too much disregard for the law and for life. And they’re not really likable characters. What keeps us invested in them is this sense that they’re good at what they do, they can’t be fooled, and they retain some shred of humanity via their commraderie.

At the end of the picture-one of their own, a poor Mexican thief, gets abused, tortured, by a local Mexican general who poses as a revolutionary but really is just as greedy, amoral, womanizing as the thieves he hires to raid a train of munitions. The Bunch then march into the General’s headquarters during a party demanding the release of Angel, their friend. When the General drunkenly kills Angel rather than let him go, the Bunch, in a split second decision, take out the general, then fight his entire army with a gattling gun and their own pistols.

Sufficed to say nobody really comes out of that all that well.

It’s here in this sequence that Peckinpah’s style came to full blossom. The orgy of blood, bullets, death must have been near unbelievable to the audience at that time.

You sense is that this is the terminus stop for violent men who have devoted a life to doing violent things. They only know how to express themselves through violence. Even their good acts (like trying to save a friend) can only end in complete obliteration.

I think this is why the best Peckinpah movies (and I’d include Straw Dogs, Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid and Bring Me The Head of Alfredo Garcia) still strangely hold up despite all their problematic elements. You sense there is a THERE THERE. A truth is revealed about the terminus stop of a life devoted to violence without reflection.

But what also makes Peckinpah interesting is his understanding of the upsetting truth that sometimes violence is unavoidable.

Peckinpah would soon go to England to make what might be, in some ways, his most atypical yet essential movie Straw Dogs. Dustin Hoffman plays David, a recently married mathematician who moves to the English countryside hometown of his wife, Amy, played by Susan George . We soon realize the move is motivated by his desire to avoid the Vietnam draft.

Still, the violence he wants to hide from, finds him.

Locals, including two who desire and/or had relationships with Amy, come to intensely dislike him. Specifically because he’s married to a local woman they desire. The resentment turns to physical violence when they rape Amy. Amy, who has repeatedly asked David to do something about the increasing violence, now loses almost all her respect for him as she deals with the trauma. Despite even this, David continues to try to avoid confrontation. Finally, when a local mentally disabled man harms a local girl and hides in David and Amy’s house, the Local Men use it as an excuse to try and destroy David’s home and, by extension, David.

At the very last moment, David realizes he can no longer avoid violence and he takes a stand.

Straw Dogs is my personal favorite Peckinpah because it asks and examines so many uncomfortable questions. At the same time, there is an extremely problematic sequence in the movie that seems to imply that Amy initially welcomes the forced sex from her former boyfriend during a moment of frustration with David’s own cowardice and weakness.

Peckinpah’s paranoia and problematic relationships with women seep into almost all his movies. But strangely, of all his movies, Straw Dogs is the one where Peckinpah seems the most self-reflective. Because Amy makes it clear pretty quickly that she actually wants the violence to stop. And she repeatedly implores David to do something. Which is a reasonable request. Also, at the end of the picture, Amy plays a critical role in defending the house and taking action. So of all Peckinpah movies, Straw Dogs is the one where the female character is given the most reasonable amount of agency and motivation.

But it’s still hugely problematic.

What I noticed this time however was that from roughly the fourth reel (when Amy and David attend a town party after the assault) through to the end of the movie (the home invasion runs for two whole reels or forty minutes), the editing is as good as anything in American 70’s cinema.

If you like Dede Allen’s cutting in Bonnie and Clyde or Slaughterhouse Five, if you like Alan Haim’s cutting in All That Jazz, you have to watch Straw Dogs. I’m putting it on the short list of the best edited American movies. Ever.

Peckinpah repeatedly does mind flashes back to Amy’s assault to show she is truly traumatized. And that David’s inaction is only exacerbating her trauma. When the local men get drunk and attack the house-breaking windows, firing their guns, shouting-Peckinpah edits it with near Eisenstienian virtuosity. I watched the movie stunned at how expert and shocking and adroit the cuts were.

When David finally realizes he has to take a stand and CONFRONT the bullies or they will kill him and Amy, we get the flip side of the coin of violence. Sometimes there are unavoidable situations-whether it be World War II or self-defense-where one has to fight an enemy who will destroy everything if not faced head on.

Here in Straw Dogs we see the collision of both sides of violence-the destructive urge to violence represented by the drunk men attacking the house and the defensive necessity to be ready to fight represented by the married couple trying to protect their home. Maybe even more profoundly, Straw Dogs makes the very real point that conflict must be dealt with. And the longer one puts off facing something, the worse it gets.

Had David addressed the bullying and intimidation right away, it’s arguable that the assault, the deaths, the violence, his marriage falling apart COULD have been avoided.

And Peckinpah seems aware of this. He seems aware that avoidance and cowardice, unfortunately, only embolden aggressors.

So all of this is to say watching The Wild Bunch and Straw Dogs was both a revelation and a cautionary tale to this programmer. These are still two relevant, important, dangerous works in cinema history.

One can see the problematic personality behind the works and how the inability to address or confront his own demons seeped into Peckinpah’s work. In a strange way, Peckinpah himself was David. And never was able to truly face his worst aggressor/bully-himself and his mental health and substance issues.

But he did clearly wrestle with the dilemma in his pictures.

The challenge for all of us filmmakers seems to be to have the humility to work on being self-aware of our faults, flaws, blind spots. And then to address them as constructively and as clear eyed as possible.

Peckinpah was a man ultimately consumed by his own demons.

But he also could rise to movies and moments of tremendous epiphany and insight and self-awareness.

Watch these movies and see what you think.

Craig Hammill is the founder.programmer of Secret Movie Club