Grand Opening: The first seven minutes of Sullivan’s Travels (1941), written and directed by Preston Sturges by Matt Olsen

Grand Opening: The first seven minutes of Sullivan’s Travels (1941), written and directed by Preston Sturges

Almost any conversation about movies will eventually find its way into a game of comparisons: “What’s the best fight scene?” “Best documentary?” “Best Nicolas Cage movie?” (The correct answers to those questions are, of course, all of The Raid: Redemption, Hands on a Hardbody, and Raising Arizona. Direct any complaints to the editor.) Now suppose you were asked the question, “What movie has the best opening?” For me, the answer is immediate – Sullivan’s Travels. The first seven minutes of the film are an exhilarating display of writing, directing, editing, and acting at the highest caliber. In other words, all of the things that make a movie a movie.

Opening Credits (0:00 – 1:39)

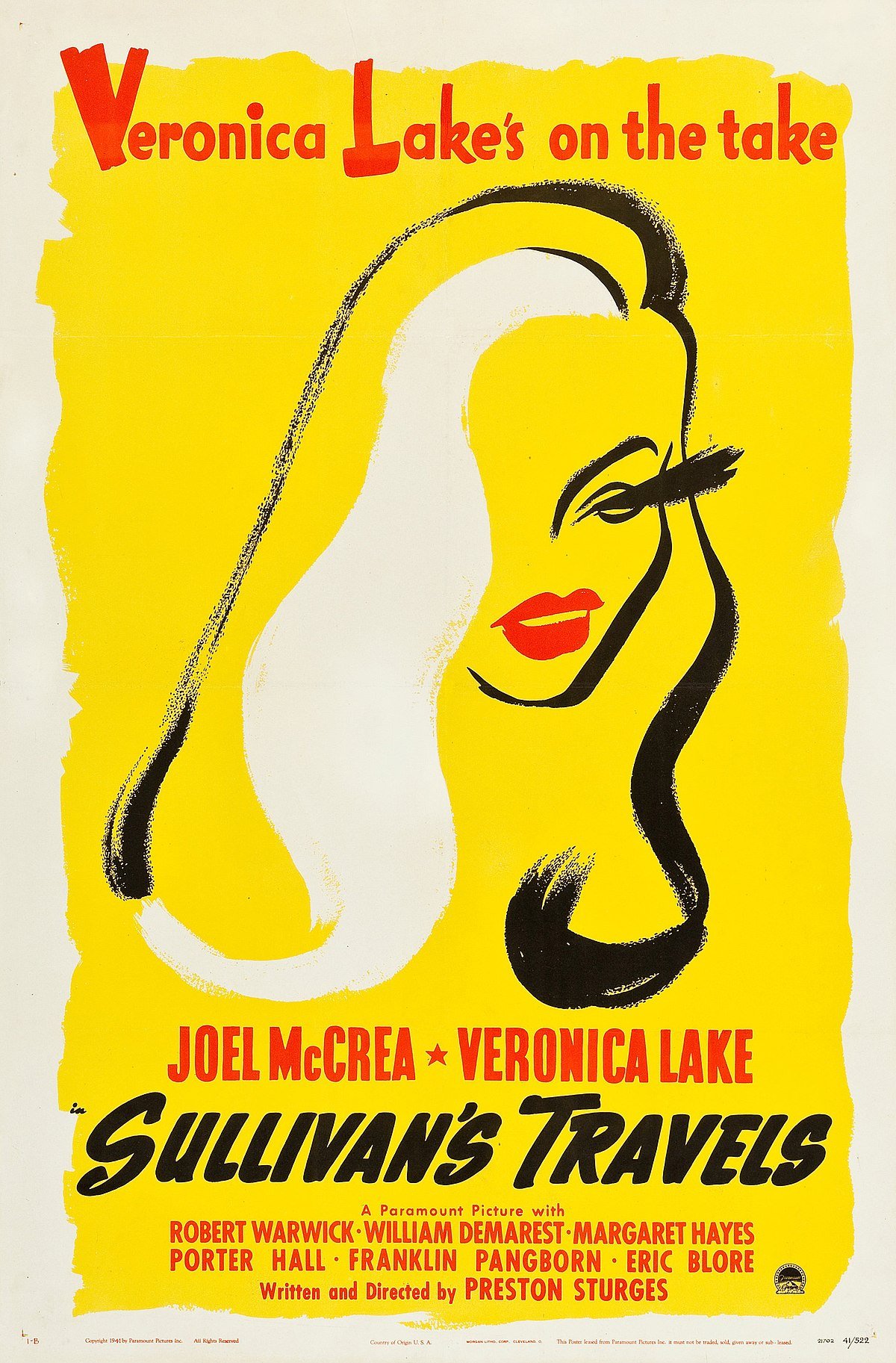

If there is a valid complaint to make about Sullivan’s Travels, it might be that the music is laid on thick and is too frequently “on the nose”. This, I think, is one of Sturges’ few blind spots across his career. Accordingly, nauseatingly sweet strings swoon while a gift is unwrapped to reveal the front cover of a large storybook bearing the film’s title and an illustration of the two leads, Joel McCrea and Veronica Lake, dressed as Depression-era hobos. A woman’s bejeweled hand turns the pages, presenting the calligraphed cast and credits. All of this, combined with the swell of the saccharine strings, suggests that what’s ahead will lie somewhere between a turgid melodrama and a fairy tale. Then, a dedication:

To the memory of those who make us laugh: the motley mountebanks, the clowns, the buffoons, in all times and in all nations, whose efforts have lightened our burden a little, this is affectionately dedicated.

The prose is certainly beyond purple but also in keeping with the tone set so far. The scene is utterly consumed by a twee sincerity which fades to black none too soon.

Train Sequence (1:39 – 2:50)

Suddenly, everything changes. The music becomes a fast-paced, tension-filled march. It’s the dead of night. Along the banks of a rushing river, a train races along its track, white bursts of steam pouring out of its exhaust. The whistle screams. Atop one of the railcars, two men are in the midst of a violent struggle. A gloved heel of one man’s hand mashes into the face of the other. The two men tumble, precariously balanced between cars. The train speeds onward, oblivious. One of the men manages to climb back to the top of the car, followed shortly thereafter by the other. The editing matches the pace of the train, the music, and the fight. A gun is fired. Four times. A man is hit – four times! – but he isn’t down. He staggers forward, black streams of blood spilling from his mouth. In a dying grip, he clenches his fists around the other’s neck. The train rushes over a bridge and the dying man propels himself and his foe off the side of the train, both falling into the dark waters below.

It’s a breathless minute and ten seconds, all the more so because, as an audience member, everything is a mystery. We don’t know who the men are, how they got there, or why they’re fighting. We don’t even know who’s the good guy and who’s the bad guy or if either are. The muddy shadows and visceral violence couldn’t be more of a contrast to the sickening syrup piled on only moments earlier in the opening credits. Wasn’t this supposed to be a comedy? And then, another twist. As the men, disappear beneath the surface, the splash resolves, the music crescendos, and the screen reads “The End”. I mean to say, what? It hasn’t even been three minutes and, now, the film is over? Surely, this is the work of a madman.

Projection Room / Private Office (2:50 – 7:09)

In an excruciatingly perfectly-timed edit presumably made by Sturges’ frequent film editor, Stuart Gilmore, the end credit and its accompanying music is cut just a half of a hair short of its natural denouement and, in an instant, the movie is a million miles away.

A cloudy beam of light emanates from the projection booth and across a small screening room. In the theater’s dimmed light, Joel McCrea jumps up from his seat, passionately raving about the film he and the other two men – his movie studio bosses – have just watched. Seemingly, this is the same film, the ending of which we, as an audience, have also seen a second ago. It’s a simultaneously dissonant and congruent moment. The next four minutes and twenty seconds of rocket-paced dialogue between the three actors is as impressive a feat of gymnastics as you’ll ever see, particularly since it’s performed primarily in one take. There’s only one cut that comes about fifteen seconds in, as the three exit the screening room and walk into the main office. From that point on, the weight of the scene rests entirely on the actors flawlessly hitting every note of the remarkable script. Which they do, like a perfectly executed piece of music or dance.

About the script – Sturges is universally celebrated as one of American film’s greatest comedic forces. His screenplays operate at a level of wit where the quantity AND quality is unmatched by almost any other filmmaker in history. He’s clearly some kind of genius, but his films could never be described as dry or cerebral, filled as they are with slapstick, pratfalls, and character types pulling faces.

In this scene, where successful comedic filmmaker John L. Sullivan, played by Joel McCrea, professes, to his studio bosses, his desire to move away from the successful populist fare of his past (So Long Sarong, Hey, Hey in the Hayloft, Ants in your Plants of 1939) and make “…something that would realize the potentialities of film as the sociological and artistic medium that it is…

His bosses, smelling a costly vanity project, attempt to talk him out of it. What’s most remarkable in this scene is that there are three distinct shifts in the characters’ status balance in as many minutes.

As the scene begins, the bosses are largely deferential, or, at least, placatory to Sullivan. They appeal to him politely but it’s clear that Sullivan holds the power. When Mr. LeBrand, the head of the studio, ultimately acknowledges that the cost of one failed picture is less than the cost of alienating their longstanding hitmaker, he agrees to let Sullivan make the “meaningful” picture he wants to make: O Brother, Where Art Thou?

It seems that Sullivan has won (status claimed) but he overplays his hand. As Sullivan continues to rant about the “troublous times”, the other studio chief, Mr. Hadrian, calls Sullivan’s bluff asking him directly,

“What do you know about trouble? ... You want to make a picture about garbage cans. What do you know about garbage cans? When did you eat your last meal out of one?”

The simple truth of this knocks Sullivan back on his heels. The two studio heads prod him with evidence of his privilege – boarding schools, college education, salaried position at twenty-four. Sullivan, chastened, accepts their argument. His status has been lost as Hadrian and LeBrand relax their attack and pepper him with possible casting choices for Ants in your Plants of 1941.

But, it’s not over. Sullivan, as if coming out of a trance, is reenergized and declares that he’s going to make HIS film. Vigorously, he concedes that to earn the right to make a film about the downtrodden he must himself know what it is to be downtrodden.

“I’m going to get some old clothes and old shoes out of wardrobe and start out with ten cents in my pocket… and I’m not coming back ‘til I know what trouble is.”

Status reclaimed, he shakes hands and hurries out. The battle is over. The studio chiefs can do nothing but accept their loss and do what they can to staunch the bleeding. In this case, that means actually reading the script for O Brother, Where Art Thou?

It’s a sequence I come back to often for purposes of both enjoyment and study. One of several lessons ripe for learning in the scene is that watching characters swap and steal power is endlessly entertaining. Screenwriting guides invariably emphasize action but rarely specify what that can include. In the opening of Sullivan’s Travels, Sturges demonstrates that action can be both physical – a bloody battle across the roof of a roaring train – and interactional – a scuffle for power within the four walls of a nondescript office on a sunny afternoon.

Matt Olsen is a largely unemployed part-time writer and even more part-time commercial actor living once again in Seattle after escaping from Los Angeles like Kurt Russell in that movie about the guy who escapes from Los Angeles.