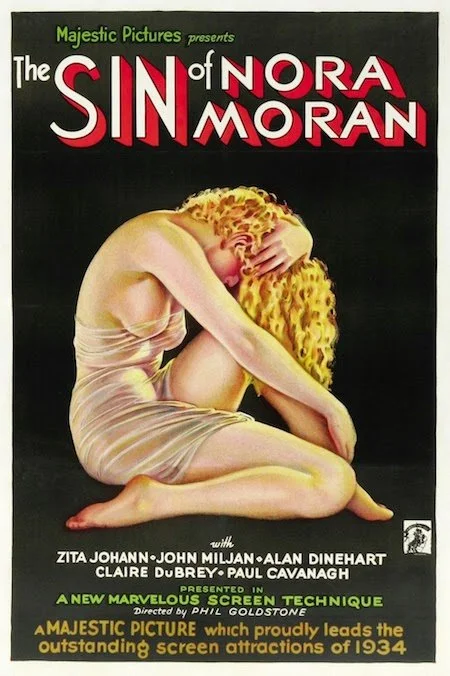

AMBIGUOUS REALITY: Matt Olsen on The Sin of Nora Moran (1933), directed by Phil Goldstone

Because the history of the Motion Picture Production Code has been well-covered many times over in the nebulous elsewhere, the following summary of the same here is purposefully brief but, I think, necessary to put the delightfully odd film, The Sin of Nora Moran, into some kind of context.

Briefly, a groundswell of moral panic toward Hollywood films (and personalities) of the late 1920s bred the formation of a self-regulated agency to impose restrictions on what could and, more significantly, could not be shown on cinema screens. The post-silent years before the strictures were firmly cemented is generally known as the Pre-Code Era. In this era, movies began tackling more controversial subject matter and, consequently, stretching out in their storytelling. Villains didn’t always die at the end and sometimes terrible things happened to undeserving people. Et cetera, et cetera. A counterpoint might validly contend that Hollywood was slavishly embracing ever more lurid elements to pander to their paying audiences.

The Sin of Nora Moran materializes in 1933, a breath away from the most robust adoption of guidelines which would have surely prevented it from being made. At least not in this form. Certainly, the lingering sequence of a bent over chorus line, camera angled directly at the high-kicking dancers’ crotches, would not have made the final cut. It’s a fairly isolated moment of brazen titillation, though, in a narrative centered around murder, including an act of sexual violence, and a shrugging acknowledgement of adultery.

On its surface, this is a story about an innocent, young woman who joins the circus, suffers torment, finds love, and, ultimately, sacrifices herself for a supposed greater good. In other words, not groundbreaking material. The film’s casual approach to reality vs. illusion separates it from other films of the era – and, arguably, even our own. The structure of the film lends itself well to uncertainty since what we see are flashback moments from Nora’s story as told by one side character to another much more tangential character.

In addition to a repeating sort of crossfade technique that slowly casts a strange diagonal shadow across the frame before transitioning to the next segment, there are two dream sequences, in particular, where the boundaries blur in intriguing ways.

The first is announced as such by both narration and the characters within the dream. Nora, awaiting execution for murder, awakes in her prison cell. It’s a setting that has previously appeared in the film but is momentarily differentiated by small changes in the set design, a kind woman from Nora’s past replaces the prison matron, and Nora now wears her costume from her time as a circus performer. In the dream, Nora has difficulty remembering the chain of events that has led her here. Struggling through a clouded memory inside a dream inside a flashback, relayed by someone else.

The second dream goes much further into the surreal. It, too, begins with a statement that this is a dream / hallucination / memory that Nora experiences while unconscious in her prison cell. In the dream, Nora is hidden away in a house across state lines with her lover, a candidate for governor. A moment of warm banter between the two, while cuddled in front of a fireplace, suddenly wobbles as Nora becomes inexplicably troubled by the stroking of her hair. Nora bolts upright, toppling an ashtray. The scene cuts back to her prison cell, the ashes on the ground have been transformed to hair clippings. The prison matron explains that Nora’s head has just been partially shaved in preparation for the electric chair. As the dream returns, the tether to reality has been loosened further. Nora has become aware of her liminal existence. She’s lost, prisoner of an oncoming doom. Time becomes fluid. Events that seem to be in the future are referred to as having already occurred and Nora describes reliving this moment many times before.

This scene transitions into a black void. Nora lays dead, in an open coffin, surrounded by candles. A priest murmurs silently at head of the casket. Her lover and his political handler, also the film’s narrator, emerge from the shadow and share this remarkably odd exchange:

“What’s the matter with her?”

“She’s dead.”

“I don’t like the way they fixed her hair.”

“They shaved part of it off.”

“Why? Why did they do that?”

“So the current can go through her head.”

“It doesn’t go through her head.”

“It goes through her head, her arms, and her legs.”

“That’s a lie!”

“It goes through her head, her arms, and her legs. If you don’t believe it, come to the execution tonight. They’re going to kill her again. The warden wasn’t pleased with the way she died.”

Even the film’s debatable flaws, such as its constant – I mean, constant – musical backing track, often static staging, and some oddly pitched performances, only add to the otherworldly feel. The lead performance by Zita Johann is absolutely compelling. While frequently wide-eyed and disoriented – as befits a character unbound from reality – the radiance and enthusiasm she expresses in the scenes of her happier times are magnetic.

By the end of the film and her life, Nora has unmetaphorically transcended the physical universe and become a messenger of calm and peace. Though, as a denouement, it’s potentially “a bit much”, it’s also perfect, entirely in tone with the rest of this peculiar and wonderful reverie.

Matt Olsen is a largely unemployed part-time writer and even more part-time commercial actor living once again in Seattle after escaping from Los Angeles like Kurt Russell in that movie about the guy who escapes from Los Angeles.