JOHN FORD: An appreciation in a prologue, 12 chapters, and an epilogue by Craig Hammill

PROLOGUE: “Saved from the blessings of civilization”

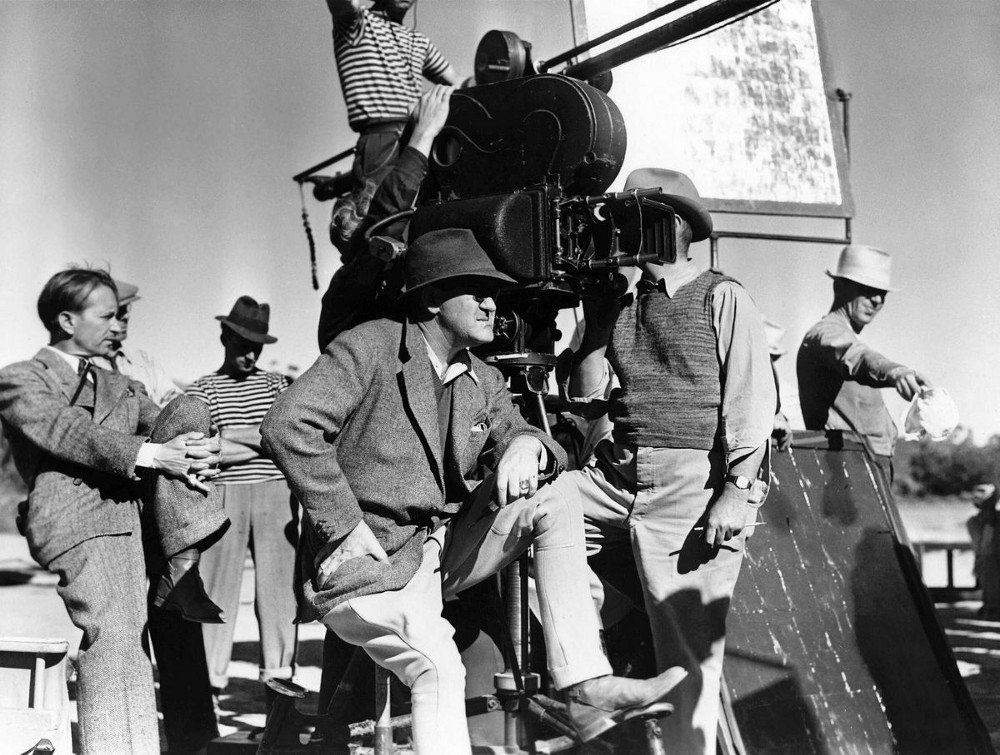

This year, we celebrate John Ford. Secret Movie Club is determined to show as many great Ford pictures as possible (and there are lots of them). On 35mm as often as possible.

Each month as we move from January to December, from Genesee to Revelay as some would say, I’ll post another chapter on this appreciation. I want it to be nutritious. Work will be done to keep from telling the same stories that have been told a hundred times just for the sake of telling them. Instead, to the extent that it’s possible, this appreciation is meant to look at both the beautiful and the ugly, the inspiring and the problematic. All the many sides of possibly America’s greatest director. Work will be done to be honest. And we’ll see where we land.

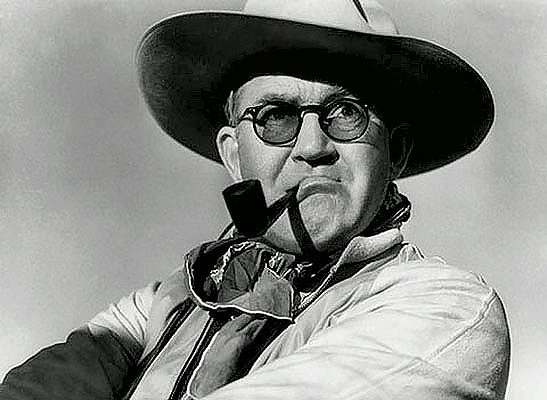

John Ford was a great man. John Ford was a problematic man. John Ford obscured his genius because he was a smart man. John Ford was a tough son of a b@#tch to deal with because he had a lot of inner demons.

When the good hearted outlaw the Ringo Kid (John Wayne) and the good hearted prostitute Dallas (Claire Trevor) ride off at the end of Stagecoach, Doc Boone (Thomas Mitchell, such a great character actor in so many of the key classics of the 1930’s and 1940’s) smiles and says “Well, they’re saved from the blessings of civilization.” The words were written by Ford’s oft-collaborator, screenwriter Dudley Nichols. Yet they somehow, quintessentially encapsulate the key paradox at the heart of all of Ford’s greatest work: Ford was an institutionalist and a bomb-throwing rebel at the same time. He devoted his life to affirming America’s (and by extension civilization’s) progress. Yet he constantly showed “how the sausage was made” to achieve that progress. And he also understood that the underlying dangers that threaten each generation- ignorance, war, tribalism, poverty, a refusal to study and learn from the past-would most likely never be transcended.

Ford seemed to truly love family, though he was often a problematic husband and father and brother. Ford truly believed in America though he often saw through the lies it told itself (and examined these lies on screen). Ford believed in professionalism and duty though he honestly admitted he felt himself a coward and suffered long bouts of mind-numbing alcoholism in between movie shoots. Ford was one of the most sensitive, thoughtful, considerate people EVER to come out of Hollywood. And at the same time he was possibly Hollywood’s greatest son of a bitch.

Ford may have had a deeply complicated sexuality but at the very least had one well known affair with Katherine Hepburn yet remained married to his wife, Mary Ford, until his death. And by all accounts, Ford remained a practicing Irish Catholic who truly believed in God all his life.

So maybe it makes sense that such a complicated, willfully stubborn, secretive, contrarian, conflicted person would turn out to be America’s cinematic poet laureate. He always had the irritant grain of sand grinding inside him to make the pearls. He was the living embodiment of how dynamic conflict yields better results.

Equally important to wrestle with is the paradox of Ford’s humanism-he was simultaneously often behind and ahead of the times socially and politically. Many of his movies-notably The Prisoner of Shark Island and the Will Rogers trilogy-have absolutely reprehensible and backwards portrayals of black folks. Yet Ford would make Sergeant Rutledge in the late 1950’s starring Woody Strode which showed how much an innocent black man would suffer at the hands of America power structures-the courts, etc-when accused of a crime he clearly didn’t commit.

Ford made countless westerns where the Native Americans were the villains but then made Cheyenne Autumn late in his career as a kind of corrective.

His honesty and insight was wildly progressive on this subject: “I’ve killed more Indians than Custer, Beecher, and Chivington put together” he would tell Peter Bogdanovich. “…I wanted to show their point of view for a change. Let’s face it, we’ve treated them very badly-it’s a blot on our shield; we’ve cheated and robbed, killed, murdered, massacred, and everything else, but they kill one white man, and, God, out come the troops.”

Ford was so beloved by the Native American tribes he constantly employed when he shot in Monument Valley that they gave him the honorary name “Natani Nez”or “Tall Leader”.

Another story that somehow captures Ford in a nutshell is one that’s always touched me to tears. During the Depression, an actor he had used in the silent era came to a Ford set to ask for money. He and his wife had fallen on hard times. Ford screamed the man off the set. “How dare you ask me for. . .” An Actor who witnessed this scene was taken aback as the poor Man crawled out of sight.

But then this actor was behind the set and saw Ford’s assistant quietly catch up to the poor Man and whisper some things assuring him that Ford would help out, he just didn’t want to be seen as weak in front of his crew. Ford paid the Man’s rent until he could get back on his feet.

What do we make of such a man? Of such a complicated man?

You’ll tell me. Or you’ll tell yourself. I can only tell you that John Ford has made some of my all-time favorite movies. They move me to tears. They are still cinematically some of the strongest work to ever be produced. Sequences from The Grapes of Wrath, How Green Was My Valley,Stagecoach, My Darling Clementine, They Were Expendable, Wagon Master, Rio Grande, The Quiet Man, The Searchers, The Last Hurrah, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, The Long Voyage Home, Young Mr. Lincoln, Fort Apache, The Fugitive to name just a very small few are as strong as any sequence in Kurosawa, Murnau, Lang, Hitchcock, Kubrick, Hawks, Scorsese, Spielberg, Coppola, Bergman, Fellini, Godard, Fassbinder, Chaplin, Satyajit Ray, Orson Welles. And in fact almost all these moviemakers admitted to being deeply influenced by John Ford.

So I’ll end this prologue by coming back to that line from Stagecoach. My personal favorite Ford. And interestingly, the ONLY movie Orson Welles studied to make Citizen Kane. Ford may have been an institutionalist on some level-he certainly believed in the American project-but he was a humanist at an even more profound level. In the end, Ford loved people. Loved the capacity of people. Believed in the potential of people. Believed in the power of God and the holy spirit to carry people to great things. This courses through all his films. It courses like electricity.

I hope some of that electricity touches all of us as we set out to make our own movies.

Orson Welles said he studied the old masters by which he meant John Ford, John Ford, and John Ford. We still have much to learn from the old man.

So let’s get ready. We might get a tongue lashing from him. Hell, he might throw a rock at our head’s for daring to call what he did art. But if we can tough it out, there’s never been a better teacher for cinema than the films of John Ford.

Here we go…

Craig Hammill is the founder.programmer of Secret Movie Club.