What Makes a Great First Movie? by SMC Founder.Programmer Craig Hammill

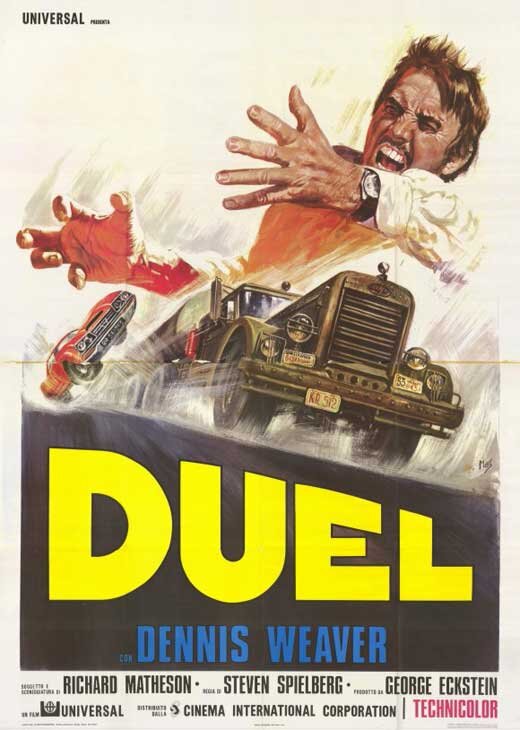

Next week, we celebrate the re-opening of our Secret Movie Club Theater after 15 months of Covid shutdown with a 35mm screening of Steven Spielberg’s 1971 debut feature film Duel.

Before anyone takes us on with the totally valid point that Duel was originally a 75 minute made for TV movie and was only later expanded by 15 minutes to a feature film (released abroad), this Programmer humbly submits that for all intents and purposes, it really should be considered a feature film.

It’s extremely special to this Programmer because it has all the hallmarks of a great debut feature: it’s ridiculously ambitious given its relatively low budget. It’s thrillingly successful in the execution of that ambition. It signals the beginning of a great voice to be reckoned with. And despite its shortcomings, excesses, road bumps (of which almost every first feature no matter how many times it gets slapped with the label “assured filmmaking” has), it works.

That magical phrase it works. Probably to really make the point though, it would be more accurate to say it works in a way that is truly great.

Spielberg’s Duel was shot in roughly 13 days on the backroads of California. It was such an arduous undertaking-film a suspense thriller action movie between an Everyman (Dennis Weaver) driving his car on a work trip and a huge big rig truck navigated by an ominous but never fully seen driver. Yet Spielberg, clearly aching to get out of TV and into features, came fully prepared. He worked out a system with his crew of getting a certain number of shots going in one direction along whatever stretch of road they had to themselves. Then turning around and getting the other shots in the other direction.

In other words, he came prepared.

But on top of this, many of the Spielberg-ian tropes that would characterize his greatest moviemaking are already evident in this first feature. He has a Hitchcockian understanding of what generates true tension. He knows that there has to be a true human element at the center of technical brilliance. And he even gets in the first of a career of mind-blowing oners (shots where an entire scene is captured in one shot) when Dennis Weaver enters a diner, goes to the restroom, and comes back out to see that the Truck Driver has returned.

This Programmer could go on forever about Duel. But like all cinema, it’s just better if you see it. So, with your indulgence, this Programmer would like to quickly prattle off a few other dynamite debuts and sketch in some thoughts about what make them great:

First up are some of the obvious yet totally important ones.

David Lynch’s Eraserhead is still one of his best movies. Along with Lynch’s total commitment to make something totally in line with his vision, the five years it took to make it show in the consummate, near Renaissance artist like craft of the work as a whole.

Martin Scorsese’s Who’s That Knocking At My Door went through tons of iterations, re-shoots, forms (and titles) as it found its final structure, length. But it still plays with dynamite stylistic bravado that we would watch only get better across decades. From the opening of a gang of locals beating up a poor guy to pop music to a centerpiece sequence of a drunk friend at a party pulling out a gun in slow motion set to Ray Barretto’s El Watusi, this first feature shows a filmmaker who gets that the most exciting cinema is a dance of content AND style.

Spike Lee’s She’s Gotta Have It is fascinating because it’s such an exhilarating blast of style, commitment to racial, sexual, and gender issues that works incredibly well and was made relatively quickly after a number of other projects fell through.

The Coen Brothers’ Blood Simple. Jim Jarmusch’s Stranger Than Paradise. Heck, we can even leap frog to the present and mention Robert Eggers’ The Witch. Ari Aster’s Hereditary. And of course just looking back, Jane Campion’s one-two punch of Sweetie and An Angel at My Table. George Miller’s Mad Max. Gillian Armstrong’s My Brilliant Career.

There are the low budget “high concept movies” that have a touch of sci-fi, fantasy, action, or horror (George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead, Andrew Patterson’s The Vast of Night, Robert Rodriguez’s El Mariachi).

There are the low budget “slice of life” movies that blow you away with how great they are at capturing ineffable truths about life (John Cassavete’s Shadows, Richard Linklater’s Slacker).

This is all subjective of course. And there are most certainly hundreds or even thousands of amazing debuts this Programmer simply hasn’t seen yet. So this list is also woefully incomplete.

But sometimes the greatest examples of mind-blowing first features are the ones that people have to recommend to you.

Evan Glodell’s 2011 Bellflower is so damn good and so hard to explain why it is so good. On paper, it sounds like the kind of movie an insecure guy makes after a really bad break up. And that’s possibly what it is. But this movie-about a guy who tricks out his car with flame throwers, takes a woman who becomes his girlfriend on an all night ride from California to Texas to get beers before it all falls apart in a nightmarishly hallucinatory way-knows it’s the kind of movie an insecure guy makes after a breakup and becomes about THAT.

It also sears your eyebrows off with a flamethrower’s heat of ambition and “let’s try this and let’s try that” grab bag experimental approach that defies categorization.

Often times, the greatest feature film debuts can’t help but be wholey themselves.

2004’s time travel micro-budget Sundance winner Primer doesn’t make a heck of a lot of sense in the final evaluation. But it does make a kind of psychological sense and has such well-thought out puzzle like moments that it becomes one of the greatest TIME TRAVEL MOVIES ever made. Great first features are also about the willingness to dare the execution of great ideas.

Or fast forward to the aforementioned 2020’s The Vast of Night directed by Andrew Patterson which is wildly ambitious for no money. A 1950’s PERIOD MOVIE(!!) about a radio DJ and a switchboard operator who begin to suspect aliens may be directly above their small town. It contains both one of the greatest opening sequences of recent memory (in which everything is set up as everyone in town arrives at a high school basketball game) and a jump for joy, go for broke, mid-movie uninterrupted tracking shot from one part of the town through the basketball game all the way to the other part of town.

Oh man. . .more examples keep exploding like a bottomless bag of popcorn:

Jean Luc Godard’s Breathless. Francois Truffaut’s The 400 Blows. Jean Vigo’s L’Atalante. Akira Kurosawa’s Sanshiro Sugata. Andrei Tarkovksy’s Ivan’s Childhood.

Maybe, all of this is to say, cinema is the fountain of eternal youth because hope always does spring eternal every time a new voice bursts out onto the scene and makes something exciting, daring, catalyzing. And that, for whatever a debut movie’s excesses, you know a great one and get inspired wildly by it because it works.

This Programmer can only end this piece by acknowledging one more, very big, elephant in the room: Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane. Kane now has the dubious honor of being so good, so influential, so pervasive, that almost no one can truly experience it anymore with the “what is this?!” freshness of 1941. We either had Kane crammed down our throats at film school or in polls or had the Kane counter-reaction of “I don’t see what the big deal is.”

But this programmer still marvels at Kane. Kane is one of those movies that if this Programmer chances upon it playing, more likely than not, he’ll stay to the end. Kane set the template for almost every great debut feature afterwards. If you look at some of the conjectured traits of a great first feature here, Kane has them all. Welles gets all his exposition across, first in a kind of baroque prologue of the moment of Kane’s death then in a burlesque parody of newsreels summarizing Kane’s life.

Then like Rashomon (but 10 years before Rashomon), we get 4-5 subjective accounts of who Kane was. Welles often described getting to direct Citizen Kane as being like a boy who got the world’s greatest model train set. And there’s something to that. Because Kane is fun. You can feel the filmmakers HAVING fun. And that too. . .on some level. . .you have to sweat blood and tears to make anything good. But you also should have fun doing it. Even a perfectionist as exacting as Kurosawa has made this point again and again: a good movie is wonderful to make.

What makes a great first movie? These are some initial thoughts. We’d love to hear yours.

Craig Hammill is the founder.programmer of Secret Movie Club.