UNUSUAL MUSICALS by Matt Olsen

UNUSUAL MUSICAL #1: London Road (2015) directed by Rufus Norris

London Road bears the dubious distinction of being a film which absolutely nobody I’ve ever met has heard of – much less seen – despite the fact that it was released in theaters in the relatively recent past, received a majority of positive reviews, features two Academy Award-nominated or winning actors in Tom Hardy and Olivia Colman, and is, to my knowledge, totally unique. You might think there’s a petty modicum of fun in me holding onto this as my own private movie experience but it would be so much more rewarding to be able to discuss it with another human being outside of my imagination. Thus, this article. Perhaps someone else will be inspired to watch the only film (as far as I know) which can be justly described as a true crime reenactment-documentary-musical/opera.

Over a three-month period at the end of 2006, five women were murdered around Ipswich, located in the Southeast of Great Britain. A suspect was eventually arrested, found guilty, and sentenced to life imprisonment. A part of what makes London Road atypical is that it doesn’t retell the story from the perspective of either the killer or his victims. In fact, they aren’t primary characters here and, in fact, don’t even appear on-screen. Instead, the film is told entirely in the world around the crimes using the actual words of real people tangential to the killings. This includes TV news reporters, sex workers, taxi drivers, and, most prominently, several of the residents who unknowingly lived alongside the murderer at the titular address.

About those “actual words”… This is the most singular facet of the movie – which, it should be noted, was adapted from an original stage production. Each and every line of dialogue has two qualities. First, they are all verbatim statements of the above-mentioned subjects, transcribed by the writer from his own interviews and reenacted by the cast. Second, and this is where it becomes an absolutely exceptional experience, all of the dialogue is sung, incorporating the natural cadence and rhythms of the original speakers. Unintentional pauses and stammers are constructed into melodies and, while the score isn’t at much risk of being confused with the work of – say – Rodgers & Hammerstein, the music is surprisingly pleasing and absolutely not a gimmicky, atonal mess as one might expect. It’s a fascinating experiment whose most impressive attribute might be its success as a both a compelling story about collective anxiety and as a stridently non-traditional but still tuneful musical. In other words, it’s like nothing else.

UNUSUAL MUSICAL #2:

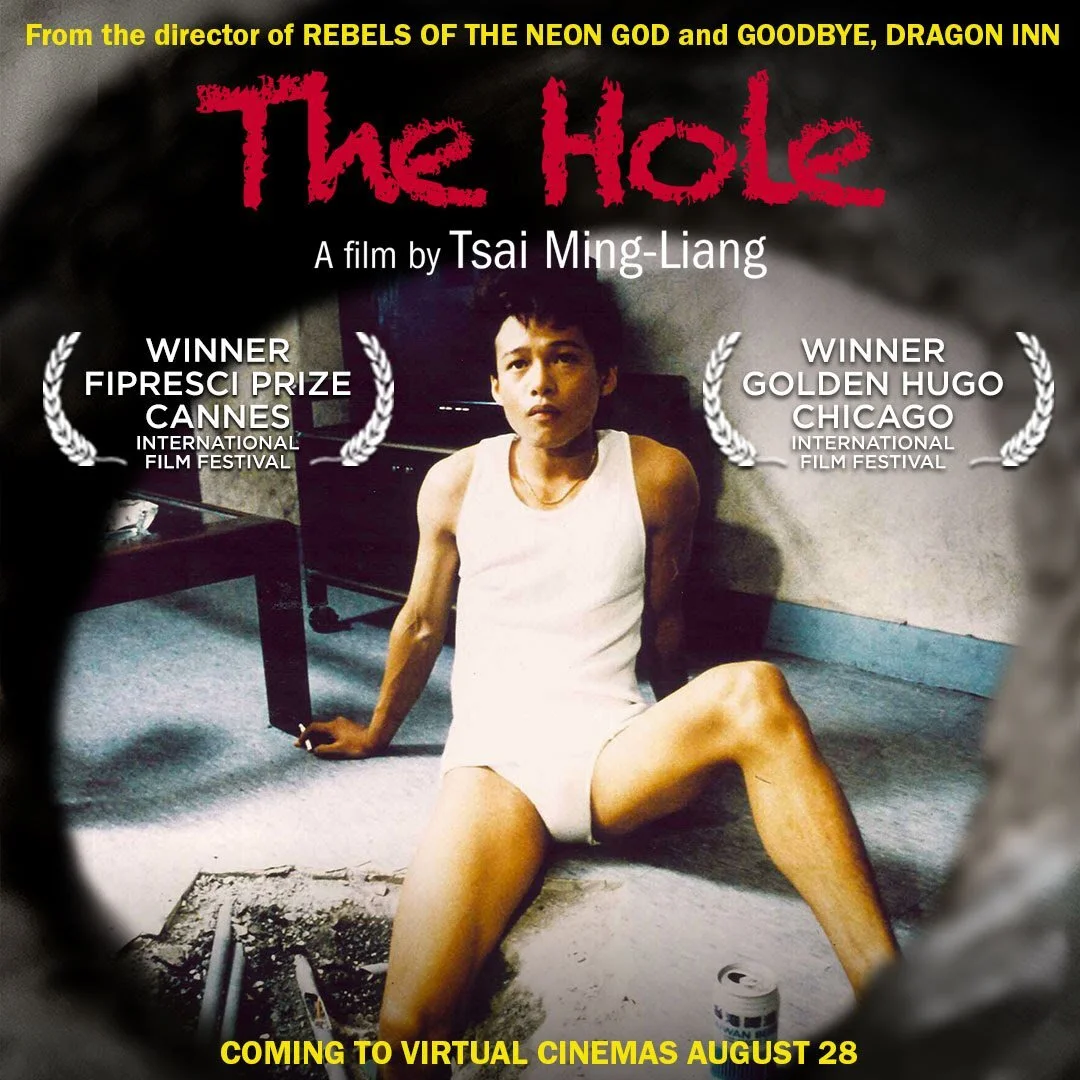

The Hole (1998) directed by Ming-liang Tsai

In the midst of a cockroach-spread viral outbreak and unceasing rains, a pair of neighboring apartment inhabitants – her ceiling is his floor – ignore government mandated evacuation orders and form a tempestuous connection with each other due to the development of the eponymous hole between their units. If this sounds to you like the typical fodder for a movie musical then you may have only ever seen this movie.

I have often heralded Ming-liang Tsai as the most extreme filmmaker working today. No one can match his affinity for long, static takes and inaction. Goodbye Dragon Inn and Stray Dogs, from what I’ll call his mid-period, challenged me as an audience member like nothing else I’ve ever seen. A particularly difficult segment of Stray Dogs will stick with me forever. Not exactly for what was on screen but for the wonderfully exasperating effect it had on the audience, myself inclusive.

The Hole, by comparison, is a breezy parade of pinwheels and popsicles. Though it contains many of Ming-liang’s hallmarks – notably in his steadfast casting of actor Kang-sheng as a quiet, alienated lead – the vibrant, choreographed musical scenes here are a complete anomaly in his filmography. So, it comes as no surprise that these highly energized sequences exist in a different reality than the gloomy, let’s say dismal, setting of the rest of the film. Despite the plague which produces cockroach-like behaviors in its hosts, The Man Upstairs and The Woman Downstairs struggle to maintain a sense of normalcy in their lives. He wanders through an abandoned open-air market to run his small grocery and dry goods store despite the almost total lack of customers. She remains in a constant battle against the leak in the ceiling (progenitor of the hole), pouring a dirty stream of water into her flooding apartment. Occasionally, and without warning, the film interjects scenes of The Woman Downstairs in sparkle-gowns, strutting through the deteriorating stairwells and hallways of the building. She’s accompanied by back-up singers, lip-syncing to 60’s-era mambo/pop/cha cha songs from Hong Kong-Chinese idol, Grace Chang.

Hopefully, that last revelation will alert the reader that this film also has a sense of humor. Very dark and dryly absurd.

As the hole becomes bigger, The Man Upstairs and The Woman Downstairs are forced to contend with their now-shared living space. Their awkward intrusions into each other’s lives become a passive-aggressive, vengeance-fueled battle of cruel intimacy. Like a well-choreographed dance, the unwilling partners advance through paces, from malicious to eccentric, ending with an unexpected act of compassion.

The 5000 Fingers of Dr. T (1953) directed by Roy Rowland

Roller-skating twin security guards joined at the beard? A despotic piano instructor with a hip-holstered baton? A grimy dungeon for “scratchy violins, screechy piccolos, and nauseating trumpets”? Obviously, the precise recipe for a guaranteed blockbuster! And yet, this, the only live-action feature with an original screenplay by Dr. Seuss was a monumental failure upon its original release. Happily, over the last few decades, the film’s reputation has grown to the extent that it may yet achieve something beyond cult classic status. It’s, of course, tempting to suggest that any maligned work is ahead of its time but, from the vantage point of this amateur film historian in 2021, The 5000 Fingers of Dr. T is as much a prime example of 1950s Hollywood musicals as its much more well-known contemporary, Singin’ in the Rain.

Though there are, perhaps surprisingly, many commonalities between Singin’ and Dr. T, what separates the two films is the unmistakable influence of Dr. Seuss. And not just in lyrics such as:

What fabulous weather for loping and leaping!

What fabulous weather for bipping and beeping!

For shnipping and shnopping and shnooping and shneeping!

From the first moment, it’s apparent that the foremost duty of the film is to transmogrify the boundless imagination of Seuss onto the screen. The production design and art direction are a marvel of twisty staircases, impossibly long ladders to nowhere, and a ubiquitous asymmetry. Most astonishing is that while matte painting backgrounds are definitely employed, the majority of what appears on screen has clearly been constructed by human hands to actually exist in our real world and without the benefit of CGI.

There are even elements of the Seuss-askew to be found in the music itself, composed by Hollywood veteran, Friedrich Hollaender. For example, the song excerpted above, “Get Together Weather” – the staging of which compares to Singin’ in the Rain’s showstopper, “Good Morning” – careens through herky-jerky syncopation and schizophrenic genre bursts while remaining undeniably catchy. An act three sequence in the aforementioned dungeon for non-pianists is an absolute wonder of invention, arrangement, and choreography. Dozens of prisoners with tattered clothing and Seuss-mutated instruments stage an ad hoc concert which relies on its bewildering arrangement in equal measure to its immaculate timing.

Like most films, the success of Dr. T rests in a large part on the performances. The four leads are all excellent – even the kid! They manage to find exactly the right tone: a reasonable naturalism in an unreasonably unnatural world. That said, the film belongs to Hans Conried as the eponymous villain, Dr. Terwilliker. Though he’s probably most well known as the voice of Captain Hook and Snidely Whiplash, here Conried demonstrates a fulsome capacity as a physical comedian. While the arched eyebrow and omnipresent sneer of Dr. Terwilliker are worthy of their own Mount Rushmore, Conreid employs a control of movement exemplified best in a scene where he escorts the young hero, Bart Collins, to the dungeon. As an oiled-up, baritone elevator operator in an executioner’s mask grimly intones the variety of torture devices on each floor, Terwilliker responds wordlessly with only a single, downward-arcing finger to suggest the ultimate horrors awaiting the boy. It’s a pure, hilarious sadism and exactly the kind of thing that you’d expect to see in a children’s film.

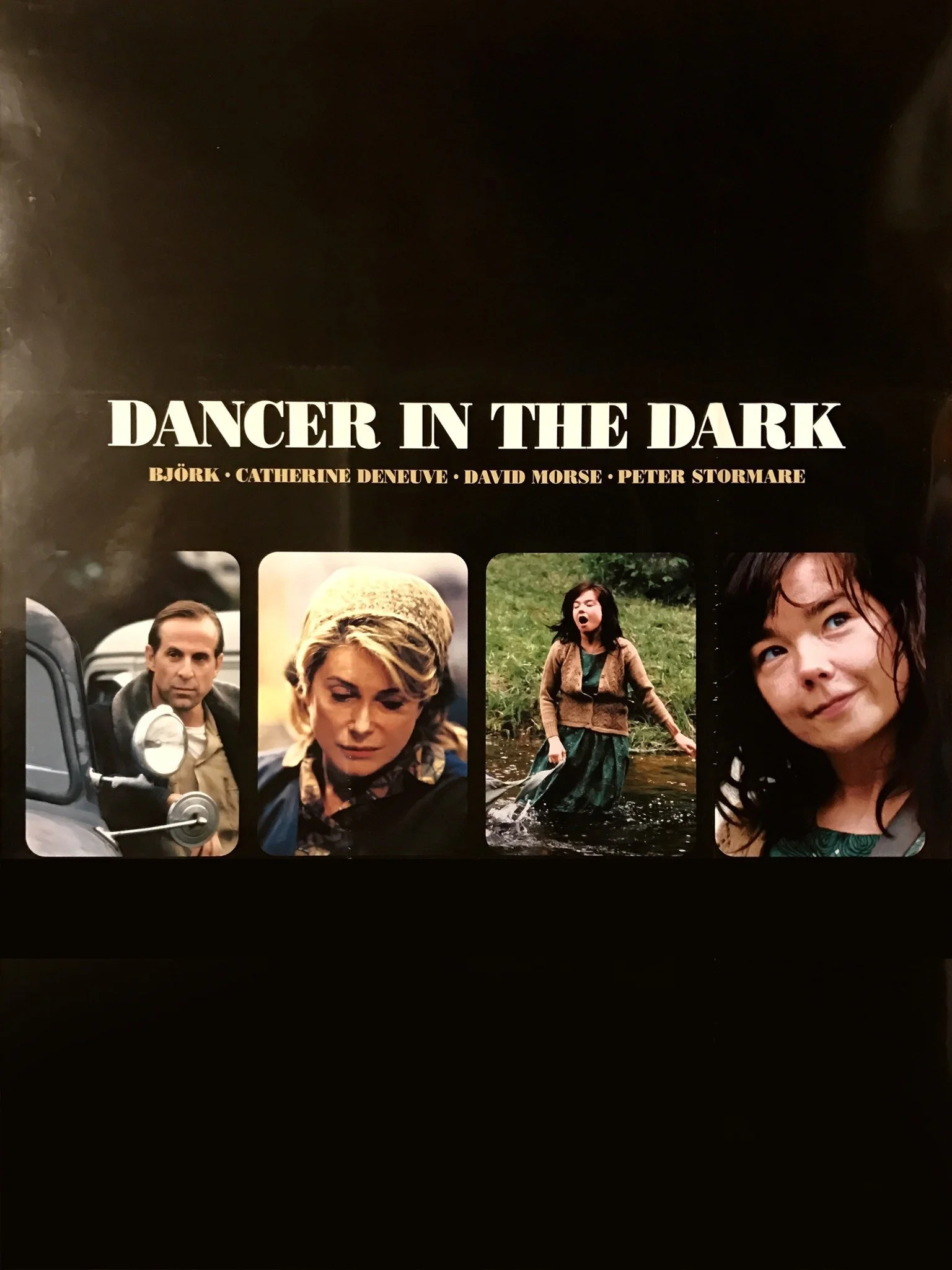

Dancer in the Dark (2000) directed by Lars Von Trier

It bears stating at the outset that Dancer in the Dark’s lead actress, Björk, has detailed a string of sexual harassment charges against the director, Lars Von Trier. Separating the creation from its creator is amongst the thorniest issues of this moment in time in particular and one, for which, I still don’t have a clear direction. There is a legitimate argument against giving further attention to films, like this, which were made at the cost of abuse to members of its cast or crew. A counter-perspective suggests that since any film is a collaborative work it’s, at least, unfair to negate the contributions made by the non-abusers. Whatever the solution, ignoring the subject wholesale is never the right approach.

In many ways, Dancer in the Dark is an anti-musical. (Where that isn’t accurate is, of course, in the music.) While musicals definitely vary in tenor – The Rocky Horror Picture Show is easily distinguished from Meet Me in St. Louis – there is almost always a sense of fun inherent in the look, story, or characters. Such is not the case here. Is Dancer the only example of a musical tragedy? If not, it’s certainly amongst the most lugubrious ever created.

Like a particularly bleak O. Henry story, every development of the story conspires against its protagonist to fuel an oncoming doom. Selma, a Czech-immigrant factory worker in rural Washington state, is going blind due to a genetic condition that will inevitably cause the same effect on her teenage son – unless she can raise enough money for an operation. Melodramatic? Without question. Such is the peculiar province of musicals. Is it any less realistic than a former nun escaping Nazi Germany with seven children and their father who has ALSO become her husband? The Sound of Music plays a supporting role in Dancer – one of the few moments of hope lies in Selma’s rehearsals for a community production of the same. This, naturally, disappears when her vision deteriorates to the point that she can no longer see her way onto the stage. When the money she has saved for her son is stolen, the story spirals into a nadir of despair from which the film never shies. Though, an outright happy ending has no place in this story, Selma makes a personal sacrifice that I would contend is a source of some small, dismal light.

Perhaps, because she is an utterly unique person in the world, Björk gives an utterly unique performance in this film. Björk’s extraordinary line delivery somehow manages to never obscure the boundless depth and sincerity in Selma. Words are accented, pitched, and whispered in ways that are entirely unpredictable and hew much closer to music than conversational speech. It’s as if she’s always singing, only waiting for the background music to join her. When the characters break into song and dance, the bursts of jubilation exist exclusively in Selma’s imagination. The physical property of the film changes in an interesting way as well. Director of Photography, Robby Müller, couldn’t be farther away from the heights he reached in films such as Paris, Texas or Dead Man. Most of the film is shot close, handheld on what appears to be high-definition video. During the out-and-out musical scenes, the cameras take a wider perspective, become stationary and the color becomes more saturated. This technique provides a clear visual representation of Selma’s delineation between reality – isolated, unpredictable, washed out – and her fantasy – communal, choreographed, bright.

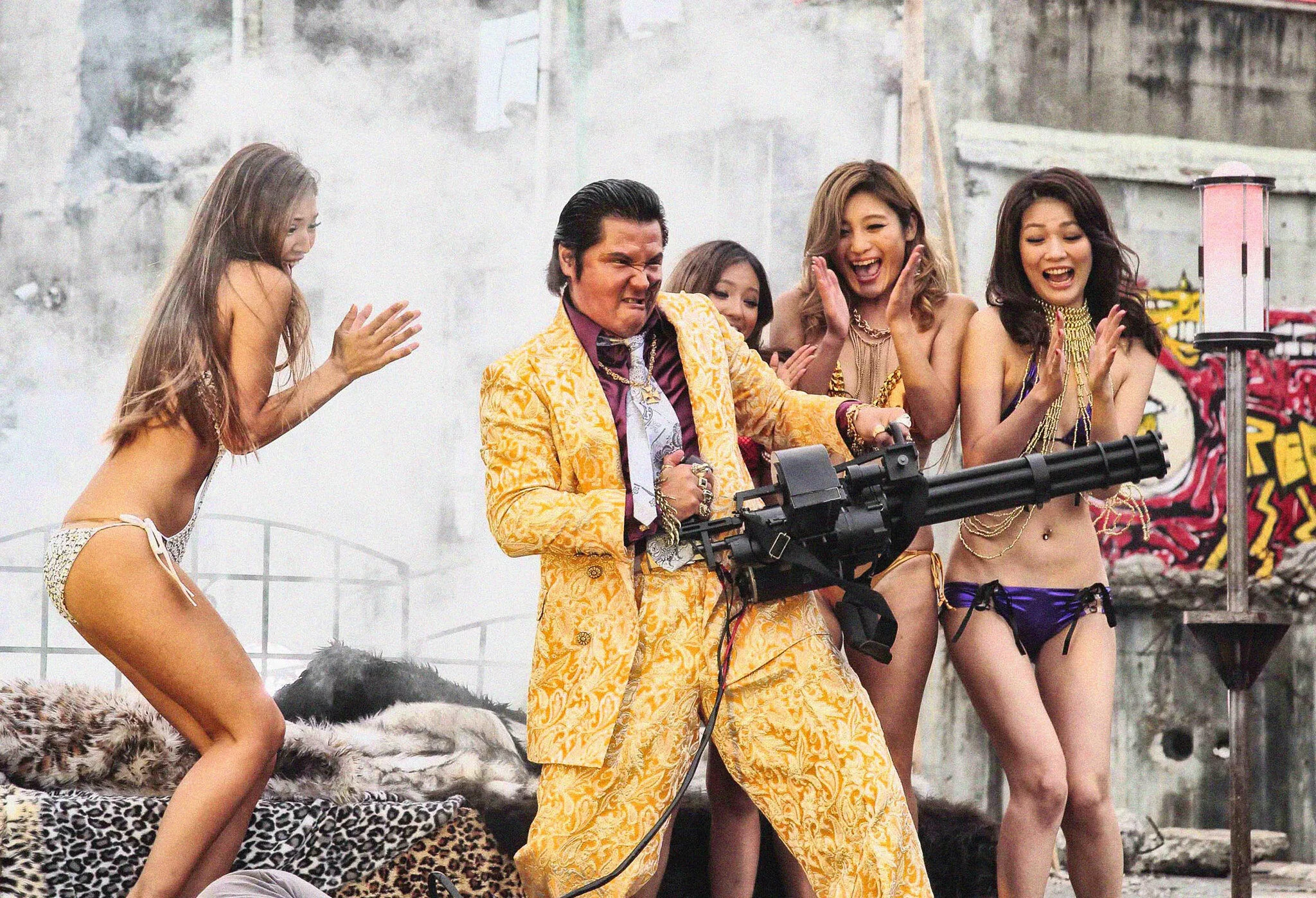

Tokyo Tribe (2014) directed by Sion Sono

In the previous installments of this series, there’s been a struggle to find enough synonyms to replace the phrase “You haven’t seen a film like this before”. That is the theme, after all. Tokyo Tribe is slightly different. This is a film based on a manga of the same name, constructed of some familiar story and film elements, and forced into a new context through the peculiarities of one of the least squeamish filmmakers alive. Attempting to summarize any of Sono’s films typically requires several footnoted paragraphs, at least – and a strong drink, recommended. Over the course of a couple of sentences on a sober afternoon, however, I’ll offer that Tokyo Tribe is the story of a gangland battle for supremacy across a hellish version of Tokyo. Divided by the eponymous tribes – each heavily influenced by differing subgenres of 90s / 2000s US hip hop scenes and styles – Tokyo here is a few blocks of neon-lit urban decay, mostly populated by criminals. So, what makes this a musical? All but a few words of dialogue in the film are delivered as a rap libretto over near-constant hip-hop backing tracks. To recap, a manga translated into a live-action film in the form of a continuous rap in the midst of bloody martial-arts ballet of violence. Cultural appropriation isn’t always a bad thing.

There’s really no such a thing as a typical Sion Sono film – he’s made at least thirty movies in the last twenty years alone – but one quality that appears with some frequency in his work is a disinterest in subtlety. In movies like Love Exposure, The Forest of Love, and here in Tokyo Tribe, the violence, blood, and sexual depravity flow without reservation. Yes, it’s graphic but the reality of Tokyo Tribe is so exaggerated, near to a cartoon-esque level, that it’s difficult to be genuinely outraged by the images and appalling behavior onscreen. A sure-to-be divisive sense of humor pervades the entirety of the film as well, effectively undercutting even the most awful scenes. As the story reaches its end, the motivation of at least one of the primary characters is revealed to be essentially a juvenile punchline. The film is an uncomfortable balance between spectacle and cheap shots and it doesn’t always level out in an excruciatingly pleasing way but it is true to itself and categorically entertaining.

Last note, a special mention must be made to the unsung hero here, the translator. As mentioned, the great majority of the dialogue is in the form of fast-paced rap lines, a form which famously requires a strong rhyme. The incredible subtitle artist manages to translate the Japanese dialogue / lyrics into an appropriate English vernacular and maintain the rhyming structures. Yes, it’s a necessary tactic in order to transmit the right feeling but the well-crafted inspired work done here shouldn’t be overlooked. I salute you, anonymous legend!

Matt Olsen is a largely unemployed part-time writer and even more part-time commercial actor living once again in Seattle after escaping from Los Angeles like Kurt Russell in that movie about the guy who escapes from Los Angeles.