The Hitchcock Meta-Theme & the conflict at the heart of his work by Craig Hammill

Although one should only take this just so far, it is interesting how some director’s bodies of work can often be distilled to a single meta-story.

Almost all of Martin Scorsese’s movies tend to be about a very flawed central character looking for some kind of redemption who goes through hell and survives at the end.

And in Alfred Hitchcock' movies, the meta theme of an innocent person accused of a crime they didn’t commit and needing to clear their own name crops up in too many of his movies to be coincidence. The Lodger, The 39 Steps, The Lady Vanishes, Young and Innocent, Rebecca, Saboteur, Spellbound, Strangers on a Train, I Confess, The Wrong Man, North by Northwest, Frenzy all carry DNA of this plot.

Hitchcock was very self-aware of this and himself pointed out he felt it was rooted in his lifelong phobia/fear of the police and being accused of something he did not do.

In those Hitchcock movies that don’t overtly have this meta-plot, there are still traces to be found. Often Hitchcock’s main characters feel guilty for crimes for which they are not really responsible and/or their repressed psychological desires are carried out by some kind of doppleganger or outside force/third party. You can see this plotline crop up in Shadow of a Doubt, Rope, Rear Window, Vertigo, The Birds.

These meta-themes are deep and present in three of Hitchcock’s 1950’s American pictures: 1951’s Strangers on a Train, 1952’s I Confess, and 1957’s The Wrong Man. In fact all three have the same basic plot: the main character is framed for or appears guilty of a murder/crime we the audience know they did not commit.

The focus on the meta-theme is slightly different in each picture.

In Strangers on a Train, tennis player Guy (Farley Granger) can’t get engaged to his high society girlfriend Anne (Ruth Roman) because his estranged wife won’t grant him a divorce. Psychotic Bruno (Robert Walker) kills Guy’s wife thus freeing Guy to marry. But Bruno wants Guy to kill Bruno’s father in return.

Here, the guilt is contradictory and profound. Bruno has “solved” Guy’s problem. Guy can now get engaged to Anne. But all motive and signs point to Guy being guilty. The fascinating aspect of Strangers is just how much Bruno acts as a kind of doppleganger representing Guy’s id.

We often see this in a Hitchcock movie. Our protagonist has a desire, wish, or feeling but DOES NOT act on it because they know it is inappropriate. But then a doppleganger appears who DOES act on it. And our protagonist must deal with the double guilt of having wished for the thing and then seeing it done through another conduit. And often benefitting from the act.

In 1943’s Shadow of a Doubt (one of the closest analogues to Strangers) niece Charlie (Teresa Wright) may never want to kill anyone as her Uncle Charlie (Joseph Cotten) wants and does. But they both share an isolating intelligence in understanding the myopia of small town behavior. Niece Charlie feels the answer is to somehow accept the rules of the game of normal society even though they personally enrage her. Uncle Charlie however has no such compunction. And Niece Charlie is unsettled because Uncle Charlie DOES what Niece Charlie only vaguely thinks about.

This translation of thought and desire into word and deed is at the heart of a lot of Hitchcock’s most effective terror and suspense.

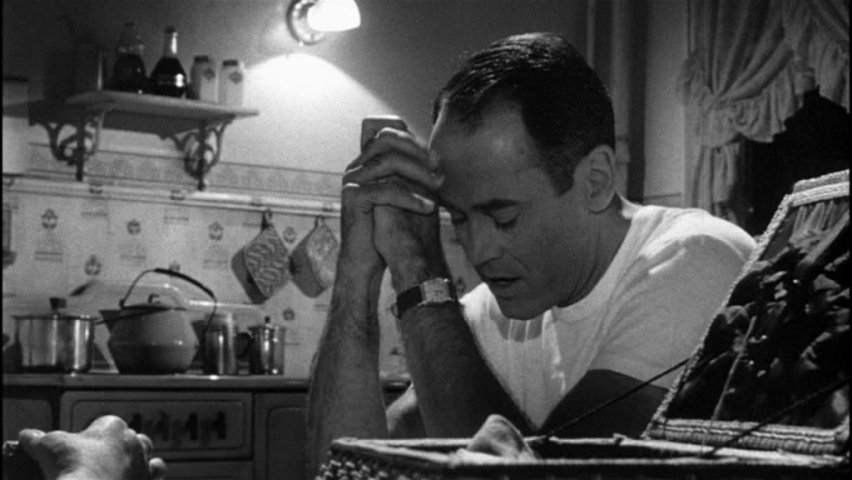

In 1952’s I Confess, our protagonist Father Logan (Montgomery Clift) also finds that his nemesis (here a blackmailing attorney) is murdered. As in Strangers on a Train, our protagonist KNOWS who committed the murder but does not tell the police. In Strangers, Guy doesn’t tell the police out of fear and self-interest (Guy is the prime suspect and nobody would believe him and Bruno has sworn to implicate Guy). In I Confess, Father Logan is bound by the rules surrounding Catholic confession. The Murderer (the German handyman who works in Father Logan’s church/rectory) confessed the crime to Father Logan the night of the murder. The rules of confession dictate that Father Logan cannot share the contents of a confession with the police.

This moral bind is even more pernicious than the one in Strangers. By being good, by following the rules of his vocation, Father Logan perversely implicates himself (again the protagonist has all the motive even if they didn’t actually commit the murder). By doing the right thing, Father Logan is acting against his own self-interest.

More overtly than in many of his other pictures, Hitchcock cinematically compares Father Logan’s plight to that of Jesus. Hitch even goes so far as to show a statue of Jesus carrying the cross as a conflicted Father Logan walks far below. Then Hitchcock shows Father Logan collapse against a wall before walking on. Thus for all those raised in the Catholic church who had to learn the stations of the cross by heart, the connection is explicit.

What’s interesting in I Confess is Hitchcock’s sincerity and emotion and somberness in this comparison. Just as Jesus was jeered by crowds who once adored him in the bible story, so too is Father Logan jeered by parishoners (who think he’s a murderer) who once looked up to him. Hitchcock seems to be saying that doing the right thing often leads to a perverse kind of punishment. But Hitchcock also seems to be saying, it is still important to do the right thing.

In 1957’s The Wrong Man, Henry Fonda’s Manny has no idea why he is suddenly pulled into the police precinct, put into jail, accused and fingered for crimes we know he did not commit. The Wrong Man (based on a true story) is Hitchcock’s most Kafkaesque foray into this theme. It may also be his most naked and vulnerable expression of his worst fear.

Like I Confess, The Wrong Man is surprisingly somber for a Hitchcock picture. Hitch himself criticized both pictures as lacking his usual irony and comedic counterpoint. He felt both movies were too serious, too heavy. And he does have a point. The Wrong Man is almost unbearable in how unrelenting the suffering is that Manny and his family must endure because of the shoddy police work and accusations of witnesses. One wonders if Hitchcock made the picture to plunge himself right into the belly of the beast of his phobias.

However just as in I Confess, The Wrong Man has some of Hitchcock’s most overt nods to his own spiritual beliefs. Ultimately, Manny prays before an image of Jesus. Hitch then does an amazing transition where the real thief walks into close up and his face overlays Manny’s face and we see just how physically similar they are. Then the actual Thief gets caught.

Neither I Confess nor The Wrong Man did particularly well nor are they as rewatched or discussed as the consensus Hitchcock classics. And that’s interesting to this writer. In a strange way, Hitchcock may have not employed the same artistic freedom and irreverence necessary for complex art here because he didn’t want to be blasphemous. And this may have lead to the somber tone and lack of playful contradictory nastiness that gives much of Hitchcock’s greatest work its zing.

Nevertheless, I Confess and The Wrong Man are crucial to proving that Hitchcock the artist (as opposed to Hitchcock the commercial filmmaker) had a profound sense of philosophical morality. Hitch wasn’t just about clever murders and film technique. There clearly was a restless mind in that filmmaker’s imagination that wrestled with the thorny moral and ethical dilemmas that bedevil all of us, daily, our entire existence.

Strangers on a Train is Hitchcock in full form, fine fettle, and playful mode. It is also the most successful of the three pictures written about today. This may be because Hitchcock’s overriding concern in Strangers is cinema and adapting Patricia Highsmith’s genius nasty debut novel in a genius nasty way. Hitch doesn’t take the material too seriously and thus, paradoxically, crafts a superior movie.

But I Confess and The Wrong Man do show the philosophical Hitchcock and this philosophical Hitchcock does appear in several of his most celebrated classics. Shadow of a Doubt, Rear Window, Vertigo, Psycho, The Birds, and Marnie are all strange strange movies that show a master showman moviemaker intent on also smuggling in disturbing themes of existential, psychological, emotional, and spiritual conflict.

This not often spoken about conflict-between Hitchcock’s brilliant cinematic instinct/craft and his restless intellect-may be at the heart of what makes him one of our greatest moviemakers.

This conflict may be at the heart of almost all great moviemakers.

Craig Hammill is the founder.programmer of Secret Movie Club