The Heavyweights: Personal favorite films of the 21st century by Craig Hammill

NOTE: Our blog series on David Lynch’s & Mark Frost’s masterwork TWIN PEAKS will return next week with Part III (Twin Peaks The Return Parts 1 through 8). We are showing Parts 5-8 this week and want to wait until our audience has gotten the chance to see the parts about which we will write.

One of the great catalysts for 21st century moviemakers is the reality that masterworks, every square inch as good as anything made, are being produced. There’s still cinema frontier yet to be explored. There are still filmic peaks yet to scale.

Like everything in art, there are the objective masterworks and then one’s own personal favorite masterworks. There’s an overlapping ven dot diagram of intersection to be sure. But the two lists are different beasts.

Today, this writer would like to discuss (with pith! with brevity!) a list of personal selections for greatest movies of the 21st century. These include Catch Me If You Can (2002), Children of Men (2006), No Country for Old Men (2007), There Will Be Blood (2007), Zodiac (2007), Un Prophete (2009), Melancholia (2011), The Act of Killing (2012), Hard to be a God (2013), Boyhood (2014), Twin Peaks The Return (2017-though this will passed over as it will be written about in depth across the next few weeks), Into the Spiderverse (2018), Lover’s Rock (2020), and The Worst Person in the World (2021).

There are a whole host of other objective great movies that are also personal favorites but I feel like they’ve already been written about so much (or we’ve already discussed them at so much length) that we can give them a break for now. These include such champions as In the Mood For Love, Mulholland Drive, Spirited Away, the Lord of the Rings trilogy, and Mad Max Fury Road.

But let’s get right to it. What makes a great movie “great” as opposed to “excellent” or “very good”? For me, it’s always been an internal quality the movie itself has that raises it to the sublime. An ineluctable style, substance, formal daring, thematic brilliance, narrative genius that lights up the film with spiritual fire.

You can feel (or at least I think you can) when a movie and its makers are operating out of their minds, at an almost inconceivable level. It’s the difference between say Spielberg’s Jaws and Spielberg’s Jurassic Park. Jaws is probably the masterpiece made under great duress but with supernatural commitment. Jurassic Park is an incredible piece of moviemaking and entertainment made by an assured master with a crack team.

So it might seem funny to some that Spielberg’s 2002 coming of age conman comedy Catch Me if You Can starts this list. Hence why I have to plead the subjective. Very strong arguments can be made that AI, Minority Report, Munich, or Lincoln better represent top tier later period Spielberg. But Catch Me If You Can, starring Leonardo Di Caprio as real life teenage con artist Frank Abagnale Jr. and Tom Hanks as his dogged pursuer FBI agent (and fictional compilation character) Carl Hanratty, feels to me like a great 21st century film.

As much as I was touched and admired Spielberg’s 2022 autobiographical The Fabelmans, it felt like maybe some punches were pulled out of deference and love for his parents. Paradoxically another person’s life (that of Frank Abagnale who forged millions of dollars in checks and successfully impersonated lawyers, doctors, and airline pilots (!!)) allowed Spielberg to get closer to the truth.

When you watch Catch Me If You Can all the elements of Spielberg’s own personal story are there-the beleaguered and somewhat abandoned father, the loving mother who nevertheless carries on an affair with the father’s best friend, and a central teenage character who hides in fantasy and fiction because the pain of real life and inability to save his family are overwhelming. But these story elements are married to a white hot Spielberg style that’s a thrill to behold. Spielberg viewed Catch me If You Can as “a glass of champagne, a confection” as he referred to it. He wanted to make something fun and come out of the dark after making the heavier AI and Minority Report. So he had fun. He didn’t overthink it. He didn’t get over reverential. He wasn’t chasing the Oscar. He just got into the trenches with great actors and an amazing crew and had a blast. And made something deeply personal. Oddly Catch Me If You Can’s nearest sibling in Spielberg’s filmmography might be 1982’s E.T. (another veiled autobiography). You can feel the joy, the pure filmmaking joy in every scene of Catch Me If You Can. It has a kind of two tiered meta brilliance in that the story AND the style are both autobiographical to Spielberg the moviemaker.

Alfonso Cuaron, like Stanley Kubrick and David Lynch, makes movies more infrequently than we greedy moviewatchers would want. But when Cuaron makes a movie, he makes it count. 2006’s Children of Men, a sci-fi retelling of the biblical nativity story in which Clive Owen’s Theo must shepherd miraculously pregnant Clare Hope-Ashity (carrying the first child the near future dystopia has seen in years) to a ship called the Tomorow. The movie’s genius is to totally sublimate the symbolism into a believable futuristic Britain, torn apart by environmental, immigration, and political strife. You’ve probably heard about the incredible “oners” in this movie-single shots that run multiple minutes. And they are stunning. But an even greater feat is how Cuaron uses atmosphere and world building to carefully craft a humanist-spiritual masterwork.

2007 in retrospect now seems like a kind of annus mirabilis. The Coen Brothers’ Cormac McCarthy adaptation No Country for Old Men, Paul Thomas Anderson’s Upton Sinclair adaptation There Will Be Blood, and David Fincher’s Robert Graysmith adaptation Zodiac all came out in 2007. No Country and Blood even shot within sightline distance of each other at the same time in Texas.

While the Coens’ A Serious Man and Inside Llewyn Davis give No Country a serious run for its money, No Country comes across as ferocious Coens. The Coens with something to prove. The Coens saying, no, wait, we still can bring the heat.

But they overcompensate and bring the cosmic fury. Aided by novelist Cormac McCarthy’s often inscrutable brutal biblical takes on the violence of man and nature of God, No Country For Old Men posits some horrible truths. Javier Bardem’s unstoppable hired killer Anton Chigurh eventually takes on a kind of demonic, supernatural power. As if the transcendent force in the universe might be one of destruction, chaos, and violence, not peace, love, and understanding. Yet Tommy Lee Jones’ startled but essentially decent police officer represents a kind of ballast to Chigurh. And Josh Brolin’s all too human Llewelyn seems to stay one step ahead of fate and disaster until he doesn’t. The three characters form a panorama of the forces of the universe.

No Country still stands as the most brutal of the Coens’ noir crime movies. But it replaces nihilism with something more disturbing and unsettling. No Country is a very thorny work and that thorniness makes it formidable to wrestle with.

Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood anchored by Daniel Day Lewis’s towering performance as oilman Daniel Plainview marked Anderson’s full embrace of the fundamentals of classic Hollywood storytelling. At the same time Anderson remained resolutely committed to the offbeat and idiosynchratic tone he had nurtured in Magnolia and Punch Drunk Love. Even surpassing his mentor Jonathan Demme, Anderson finds a way in this movie to make BOTH a powerful anti-heroic epic AND a truly strange shaggy dog of a movie. While Anderson’s The Master may be as good (or even better), There Will Be Blood has the kind of startling presience that are imbued in only a few movies. Blood sees the squid versus the whale partnership/contest between Day Lewis’s oilman and Paul Dano’s preacher Eli Sunday as a telling metaphor for the uneasy alliance between pragmatic American business interests and American religion. But it sees the cynicism that underlies the entire endeavor and the rotting out of the American soul that may be yet to come.

David Fincher’s Zodiac, even among all these amazing movies, may be one of my top three or four favorite 21st century movies. Fincher commits to showing the terrifying spree of the real-life Zodiac Killer in 1960’s and 1970’s California through the effect the never truly solved murders had on those who tried to solve them-journalists, detectives, amateur sleuths, opportunists. Fincher’s obsessive interest in procedure has never had greater vent for expression than here. But, for my money, Fincher finally achieves a kind of philosophical profundity here that is rare. Our lives run concurrent with horror and tragedy. And time, ultimately, has the final word on the good and evil alike. Things often are not resolved how we would wish or want them. Yet something does get discovered. Something does get progressed.

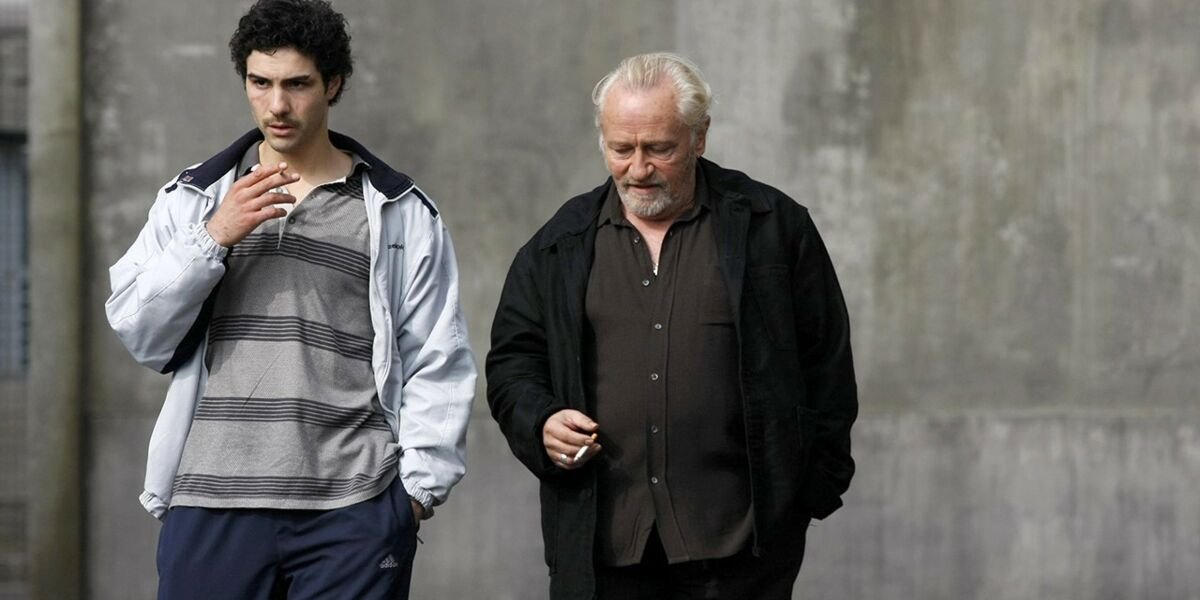

2009-French filmmaker Jacques Audiard’s Un Prophete is a 21st century The Godfather married to the spiritual rigour of a Robert Bresson movie. Malik (a superb vulnerable and powerful Tahar Rahim), a French Algerian petty thief, rises through the ranks of the Corsican mafia in prison until he becomes kingpin Neil Arestrupe’s (a towering performance) most trusted lieutenant. At the same time, Malik has a strange spiritual awakening after he kills a fellow Muslim in prison for his own survival. The movie has the audacity to feel like a triumph and a tragedy and to end on a truly strange, jubiliant, yet ambiguous note of ascension to power.

Lars Von Trier’s 2011 Melancholia is about the end of the world as seen through the eyes of Kirsten Dunst’s chronic depression . Because Dunst has stared into the void through her own depression she’s oddly best equipped to accept the utter destruction of the human race. Lars Von Trier has never lacked for ambition and in Melancholia, he comes near the audacity of Breaking The Waves.

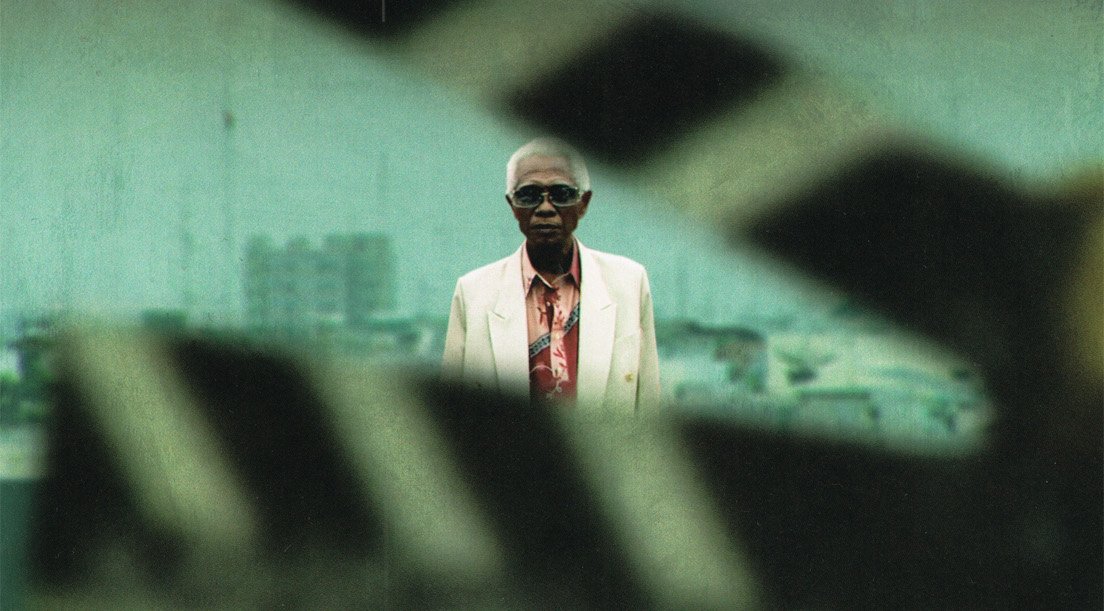

Joshua Oppenheimer’s 2012 documentary The Act of Killing tells the story of how Indonesians were hired to kill other Indonesians to rid the country of Communists. And then how those killers were celebrated as national heroes. Oppenheimer has the actual killers tell their stories and even enact strange surreal “performances” showing how they performed the killings. But he also manages to show how these killers are clearly haunted by their actions. BUT, at the same time, he shows that these killers are NOT sociopaths. They are working class people with families, grandchildren, senses of humor, who somehow allowed themselves to be conscripted into mass killings.

Russian filmmaker Aleksei German died in post production on his years in the making 2013 sci-fi epic Hard To Be A God. So his family finished it for him. The resultant work though is utterly singular: a movie about a scientist from Earth who masquerades as a Duke on a planet like ours that never progressed beyond the brutality of the middle ages. A possible metaphor for the filmmaker’s feelings about modern day Russia, the movie nevertheless is stranger than just political metaphor. You FEEL like you are on another planet. And because the earth scientists have all taken the pledge NOT to interfere with the planet’s society and evolution (or non-evolution) all they can do is watch and grow increasingly furious at the stubborn ignorance around them.

Richard Linklater’s 2014 Boyhood, also a long gestating project, tells the laid back emotional story of Mason (Ellar Coltane) growing up in Texas from six years to eighteen years old BY using the same actors including Patricia Arquette’s Mother and Ethan Hawke’s Father across twelve years. The result adds a layer to cinema one sometimes encounters (and even then just barely) in documentaries: the layer of the passage of time. The Boy’s story is very singular (clearly modeled after Linklater’s own childhood) yet universal. Divorce, moving homes and apartments, alcoholic and problematic stepparents, siblings, life choices all get explored with great soulfulness YET no scene is ever forced or melodramatic. By the end of the movie, you feel like you’ve really watched part of a life. Yet by stopping at 18 years of age, Boyhood also imparts the feeling that the most exciting parts are yet to come.

David Lynch’s and Mark Frost’s 2017 Twin Peaks: The Return which they always viewed as a feature film in 18 parts (even though it was made and exhibited as a limited series on Showtime) will get discussed in greater detail in the upcoming weeks. For now, I just want to say I consider it the greatest movie of 2017 and one of the greatest of the last 23 years.

2018’s Into the Spiderverse shocked me because it managed to accomplish what other superhero movies only accomplished in part (in my opinion): a diverse, representative superhero movie that is wildly entertaining, boldly stylish, laugh out loud funny, and successful without every feeling like it is virtue signaling or foregrounding its agenda to pat its own back on its goals. The movie is just great. Its politics, if you want them, are there, but so baked into the cake they never distract.

Steve McQueen’s 2020 Lovers Rock was part of his SMALL AXE series of five feature films about the black experience in Britain from the 1950’s through the present day. Lovers Rock takes place entirely across one night in 1980 at a raucous house party thrown by London’s vibrant West Carribbean community. The movie is a tiny miracle of a film. In its just over 70 minute running time, mostly spent watching folks dance, romance, fight, drink, sneak out of houses, return to houses, we somehow feel communicated the vitality, independence, indignation, and anger of an entire generation.

Finally Norwegian filmmaker Joachim Trier’s 2021 The Worst Person In The World tells the story of twenty something Julie as she changes careers and boyfriends across pivotal years in her life until she finds herself square in the center of adulthood, still searching. What makes this movie truly great is how Trier imbues Julie’s story with a cinematic style that matches how we feel at that age: big, operatic, light on its feet, magical, full of potential. Though the decisions we’re making may not be of the “life and death” variety, they nevertheless set us on the trajectory for the rest of our life and deserve the merit of full worth and consideration. Renate Reinsve’s performance as Julie grounds the story and also saves it from feeling too much like a middle aged white guy wondering what’s going on with his millenial or generation z girlfriend. Though the perils of that kind of viewpoint occasionally make the movie feel like its stumbling, the underlying humanism, cinema, and force of filmmaking raise it to the level of great 21st century movie.

Okay! Whew. I didn’t realize what I was biting off here. For now, I hope this appreciation whets your appetite to check out or revisit some of the movies mentioned above.

At the very least, my humble desire is that you see something here (or in your own subjective list of 21st century favorites) that affirms for you that cinema is alive and well and has more vast expanses in which to travel. More greatness yet ahead of it. Let’s seek out these expanses. Let’s commit and struggle and work and refine and continue to produce new, original, exciting great movies.

Craig Hammill is the founder.programmer of Secret Movie Club.