The deep profound simplicity of De Sica's masterpiece UMBERTO D by Patrick McElroy

Fred Rogers once remarked, “I feel so strongly that deep and simple is far more essential than shallow and complex.” Throughout film history those ideals have never been better explored than by Italian neorealism. A style of filmmaking that emerged in Italy in the following years after WWII, most of the establishments had been deconstructed, and society had been poverty stricken. Filmmakers, with the little they had made films to confront the harsh new world, along with the struggles of the working class who were readjusting and trying to make ends meet. They were often made with non-professional actors, in stripped down black and white, and on locational to give it a sense of naturalism that was contrary to the glamour of the Hollywood golden age.

The three directors who were associated with this style were Roberto Rossellini, Luchino Visconti, and Vittorio De Sica, the latter of which made the best known and most iconic film The Bicycle Thief (1948). While it is one of the greatest movies ever made, it’s unfortunate that it’s the only neorealist film that gets talked about, so much so, that in 2013 Gianni Bozzacchi made a documentary titled The Neorealism: We Were Not Just Bicycles Thieves.

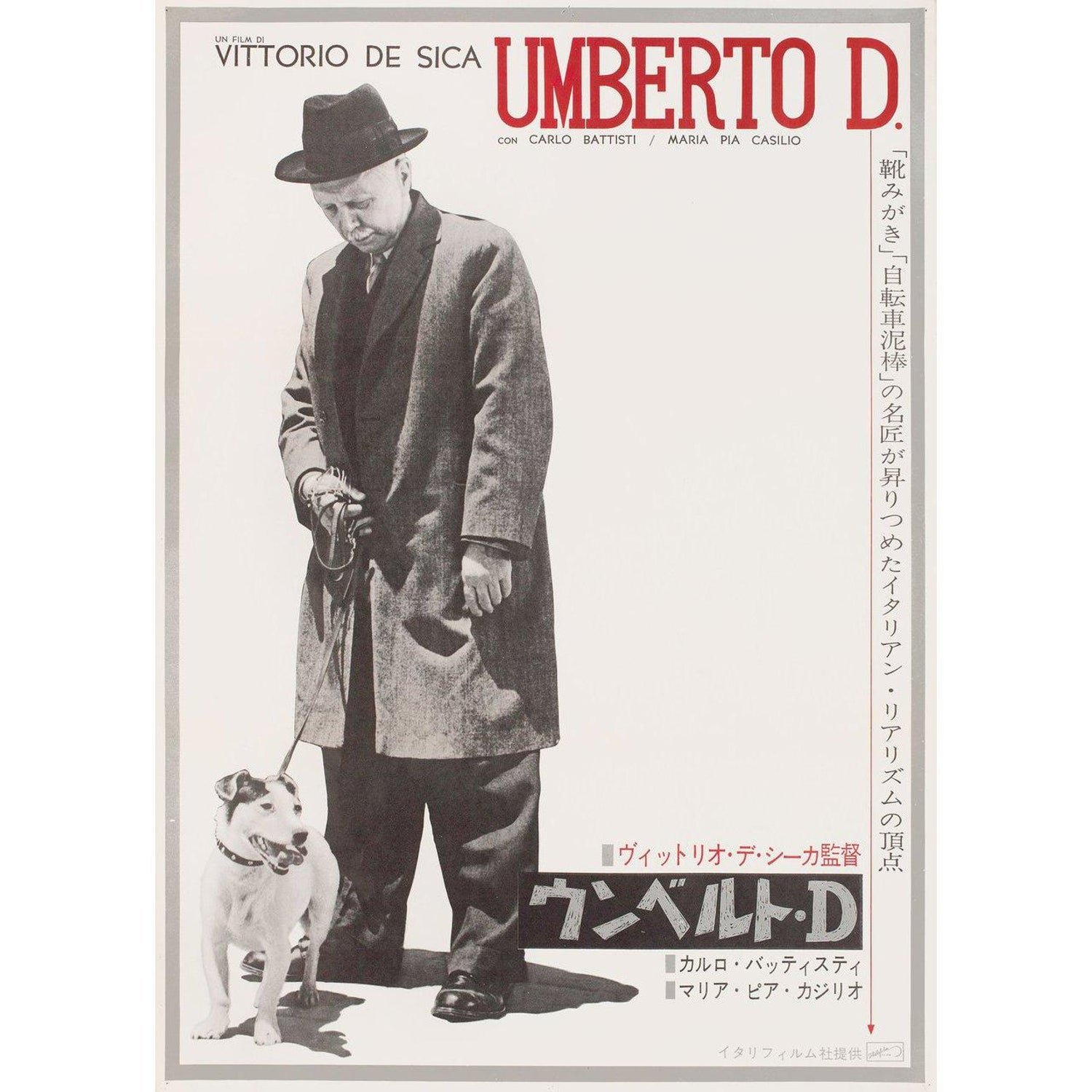

There’s one film from De Sica that I along with Martin Scorsese prefer to The Bicycle Thief, and that’s his 1953 film Umberto D. The film follows Umberto D. Ferrari (Carlo Battisti, a non-actor) a former government employee, and his little Jack Russell Terrier Flike, as his landlord threatens to evict them by the end of the month if he’s not able to pay rent. As the film progresses, we see Umberto try to get rid of Flike to a few different people feeling he can’t support him, but he keeps on being drawn back to him as it’s the only source of love he has left in his life. When the movie was made, it was to show how much of Italian society had neglected the elderly, whether it was economically, or emotionally. The film wasn’t as popular in the country upon its release, because the economy was starting to bounce back, so audiences found the movie too critical of the country, but it was however successful in other countries.

Ingmar Bergman once declared it as “a movie I have seen a hundred times, that I may love most of all."

De Sica was heavily influenced by Charlie Chaplin, through his simplicity, and directness. He transported powerful emotions to audiences worldwide. Perhaps the most Chaplinesque scene in the movie is when Umberto and Flike are on the street hoping to make money, he holds out his hand while a man walks by about to hand some, but Umberto is looking the wrong way and is actually checking for rain, so he folds his hand over. This small gesture presents us with humor like Chaplin’s that is simple and pedestrian, but also shows the struggles one faces.

In my piece on Jean Renoir’s The River (1951) I wrote about how in the following decade after WWII, many filmmakers were given the challenge of showing what made life worth living, with De Sica’s previous two films The Bicycle Thief, and Miracle in Milan, he almost forms a trilogy with Umberto D. of exploring this theme.

Through Umberto’s relationship with Flike, it’s like the relationships each of us have with our own lives, we want to get rid of them in times of despair thinking we can’t support them, but somehow were always drawn back to them, because there is a form of joy that can come through it, versus the bleakness of nothing.

One of the most moving and heartbreaking sequences in any movie is when Umberto thinks he’s lost Flike, he goes to a dog shelter hoping he’ll be there. He then see’s that if dogs don’t find their owners after a while, they’ll be incinerated, he doesn’t see Flike there, so he worries that maybe he’s been incinerated. Then comes a moment that always bring me to tears, as Umberto’s leaving a truck pulls in that to his relief has Flike, he rushes over and embraces him, cutting to a close-up of Flike with is face nuzzled into Umberto’s neck. We may take our lives for granted, like Umberto did with Flike, but when we feel we might lose it, we then realize how much we want it. We live in an era where many of us feel as if we should give up, but this movie show’s that there’s always something that keeps us moving, even if its in the form of a small furry friend.

Patrick McElroy is a movie writer and movie lover based in Los Angeles. Check out his other writing at: https://www.facebook.com/patrick.mcelroy.3726 or his IG: @mcelroy.patrick