The David Lynch style, Twin Peaks, and the first two seasons (Part 1 of 4) by Craig Hammill

Rewatching a movie or TV series is a beautiful new experience. Now that you’re familiar with the material, you enter a new level of engagement. Rewatching the first two seasons of David Lynch’s and Mark Frost’s Twin Peaks which aired in 1990-1991 on ABC, a tension becomes very clear.

There are aspects of the show which clearly obsess Lynch and Frost, namely the murder of Laura Palmer, spiritual straight shooter FBI agent Dale Cooper who comes to investigate the murder, a kind of interrogation of small town community, and the complex nature of good and evil deeds with a belief that travels into the transcendent. .

But then you also notice there are aspects of running an episodic TV series that probably held less interest for Lynch specifically: the constant grind of ginning up new prime time soap opera twists that keep the viewer waiting during the commercial break (back when commercial breaks were a thing). And the sheer brutality of having to somehow produce 22 episodes (approximately 17 hours of television) in 10 months whether inspiration hits or not.

This tension between the cinematic essence and integrity of David Lynch and Mark Frost and the pragmatic realities of network television produces some wildly uneven results (specifically in season 2). But it also produces at least four of the greatest episodes of television ever produced: the 90 minute pilot “Northwest Passage”, Season 1 Episode 3 “Zen or How to Catch a Killer”, Season 2 Episode 7 “Lonely Souls”, and Season 2 Episode 22 (the series finale until Twin Peaks: The Return) “Beyond Life and Death”. All directed by David Lynch and co-written and/or showrun by Mark Frost.

There’s also something about this alchemy (Lynch/Frost/network television) that is utterly singular in David Lynch’s body of work-including the 1992 feature Twin Peaks Fire Walk With Me and the 2017 Showtime limited series Twin Peaks: The Return. The ABC network TV episodes seem to be in constant dialogue with themselves: there’s at once something bracingly cinematic and strange AND perfectly suited to the medium of network television about the best of this network shows. Even at its worst (and this writer does share Lynch’s own assessment that much of season 2 after Laura Palmer’s murderer was revealed does not work), the show is a cut above of much of what was showing at the time.

The David Lynch directed episodes (which also include the Season 2 ninety minute opener “May the Giant be with you” and Season 2 Episode 2 “Coma”) are uniformly darker than the non-Lynch directed episodes. They also include elements of the Lynch style that just don’t carryover in non-Lynch episodes.

For some reason, Lynch knows how to shoot and use insert shots (a close up of a fire, a streetlight turning from green to red in the middle of the night) in an unsettling way. Even when these shots were reused in other episodes, the rhythm feels off. In the Lynch episodes, the rhythm of the cutaways feels darkly musical and unsettling.

Lynch also clearly has a tremendous grasp on how to use abstractions. His episodes contain the most successful uses of characters who seem to exist on a transcendent plane like the otherworldly personification of the evil that lurks in the human soul BOB, the Man from another Place, the Giant. Save for the occasional flashback or cutaway that pop up in non-Lynch directed episodes, the otherworldly purgatory known as the Red Room only really takes center stage in the Lynch episodes.

In fact, after the 12 or so episodes of season 2 which struggle to find a mystery to compare to the murder of Laura Palmer (and thus regrettably hint at things like aliens, demonic forest spirits, characters who fake their own deaths, 40’s noir femme fatale insurance schemes, FBI agent Dale Cooper in flannel (!!) etc), Lynch dedicates the season 2 finale almost exclusively to re-centering the Twin Peaks formula. It’s telling that Lynch’s on-screen character, FBI Director Gordon Cole, appears in the final few episodes and kicks them off by telling Dale Cooper he’s been re-instated in the FBI and to get out of flannel and back into the suit.

Lynch and Frost spend the first half of the Season 2 Episode 22 finale with unsettling scenes showing the town of Twin Peaks in some kind of purgatorial loop. This blurring of temporal reality gets pushed further in the movie and Season 3. But we see it start here when Shelley and Bobby repeat the exact same dialogue to a tardy waitress at the Double R Diner that they did in the Season 1 pilot. Yet all the characters seem to be unaware that “it is happening again”.

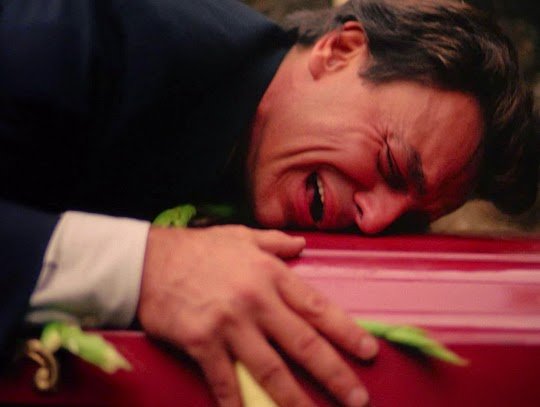

Then Lynch plunges us into the Red Room for a literal second half spent in Purgatory and other worlds. Also, in this final episode, while Lynch does address several storylines generated mostly in his absence, he emphatically brings back Laura and Leland Palmer (who appear as both their good and bad selves in the red room) as if to remind everyone why the series worked in the first place. Laura and Leland had actually been completely absent season 2 after episode 9 and that absence is painfully felt.

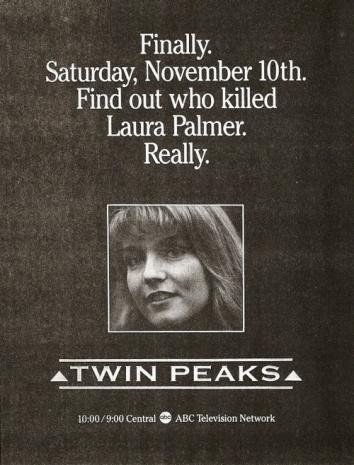

Lynch has often said the big mistake of the ABC years of Twin Peaks was revealing who killed Laura Palmer. Lynch has often referred to this as killing the goose that laid the golden eggs. For a while I wasn’t sure I agreed with Lynch as this decision produced one of the greatest hours of television ever (the murderer reveal in Season 2 Episode 7’s “Lonely Souls”). But now on re-watch, I realize Lynch was right and ahead of everyone else.

As talented moviemaker and audience member Jesse Percival pointed out to me: revealing Palmer’s killer and wrapping up that mystery took all the mystery out of all the other storylines. Until then, any storyline could, ultimately, feed back into the Laura Palmer storyline. But once the Palmer storyline was resolved, all the other storylines felt more blandly soap operaish. As if the central masterwork building in a constellation of buildings got torn down thus revealing how inferior all the surrounding buildings actually were by comparison.

Lynch probably knew this. And from what I can gather, he either NEVER wanted to solve the mystery (only deepen it) or he wantd to do so only in the series finale several years later. It feels probable we would have gotten “Lonely Souls” but just as the final episode and in a different form.

Yet, the paradox here is that by forcing Lynch and Frost to reveal the murderer, Lynch and Frost were forced to find ways of continuing the story that actually took the series to even deeper, stranger, more satisfying places. Season 3: TWIN PEAKS THE RETURN is essentially a series launched from the prequel/sequel feature TWIN PEAKS FIRE WALK WITH ME and the Season 2 Episode 22 series finale. So maybe everything happens for a reason.

Finally, there’s a kind of balance in the Lynch/Frost overseen first season and the Lynch directed episodes of the second season that feels like a Twin Peaks golden mean: there’s the deep humanity Lynch has always had that embues the ensemble of characters with more balance and gravitas. There’s a love and fascination with his characters without ever insulting them. There’s an absurdist humor pushed to its breaking point that only Lynch and Frost together would have the audacity to commit to. The Season 2 Episode 22 sequence in the bank with the elderly bank teller and a similar sequence in Season 2 Episode 1 with an elderly room service waiter presage Lynch’s The Straight Story. No other director on the series pushed scenes to their “slow cinema absurdist” breaking point like Lynch. And in fact, the entire Dougie storyline in Season 3 seems to take this gauntlet and cross the Rubicon. (And in this writer’s opinion, succeed wildly once you give yourself over to it).

But finally, maybe it also has to be acknowledged that the masterworks to come: the feature Twin Peaks Fire Walk With Me and Season 3 TWIN PEAKS: THE RETURN could only come into existence from the fraught struggle and birth, trial and error, of seasons 1 and 2. Swords are forged in fire and banged out on an anvil until the metal coheres into cool unity. Until that moment, they are plunged back into the coals, deformed, mishapen, re-hammered, until the unity is achieved.

Twin Peaks Seasons 1 and 2 feel similarly in the midst of this forging process. Yet for all their imperfections and missteps, they are two of the greatest seasons network television ever produced. It is not hyperbole to state that shows like The X Files, The Sopranos, Breaking Bad, The Wire, The Walking Dead, Lost, to name just a few had runway because Twin Peaks broke the ground to build the airport. Before Twin Peaks, you could point to Rod Serling’s The Twillight Zone, Ingmar Bergman’s Scenes from a Marriage and Fanny and Alexander, Fassbinder’s Berlin Alexanderplatz, and John Cleese’s Faulty Towers as an ur-proof of authorial idiosynchrisy that could capture the imaginations of a wide swath of the world. Twin Peaks, however, was the first homegrown American masterpiece since Twillight Zone to take some of the wildest tonal risks in television history.

Maybe Twin Peaks greatest feat is in serving as prologue to two of the most harrowing, intense, philosophically challenging works of art of the last thirty years: the feature Twin Peaks Fire Walk with Me and the 18 part feature (as Lynch always conceived of it) Twin Peaks: The Return. Both of which we’ll look at in detail in the next three parts.

Craig Hammill is the founder.programmer of Secret Movie Club.