THE CHILDREN OF EISENSTEIN by Craig Hammill

Over the last seven plus years, you may have heard me opine about how I think there are traceable lineages in cinema. It can almost be biblical if you want. German expressionist genius F.W. Murnau (The Last Laugh, Sunrise, Nosferatu) begat John Ford who begat Akira Kurosawa and Ingmar Bergman who begat…

Then recently another lineage seemed to pop its way into my consciousness. And I was embarrassed I’d never really put it together. The other German expressionist maestro Fritz Lang (Dr. Mabuse, Metropolis, Die Nibelungen) begat Alfred Hitchcock who begat Brian De Palma and David Fincher who begat. . .

And I thought that was it. No more begatting.

But then it hit me. I’d left an entire genealogy unacknowledged that was so clear it had been staring me in the face just inches away from my nose.

Russian montage master moviemaker Sergei Eisenstein (Strike, The Battleship Potemkin, Alexander Nevsky) also has a tribe that doesn’t fit neatly into the Murnau and Lang camps. And these are some of our best moviemakers. The moviemakers who embrace montage and dialectic editing as their primary tool.

If Murnau’s lineage produces the humanist moviemakers who experiment with all the tools of cinema and Lang’s lineage produces the precise moviemakers who embrace and push the technology to the limit, Eisenstein’s lineage produces the moviemakers who find ways of joining Shot A to Shot B that shock and surprise with the “third” idea created in the edit itself. These moviemakers include French New Wave pioneer Jean Luc Godard and 70’s American boundary pusher Martin Scorsese. Working to get us closer to the present moment, I might nominate George Miller and 2015’s Mad Max Fury Road as a kind of cousin to the montage/dialectic editing school. Action movies have always struck me as being about the felicities of cutting or adding one frame here or there that makes all the difference in selling a stunt, an action sequence, an impossible moment that can only be accomplished through editorial slight of hand.

And so by extension, we probably have to look at master action moviemakers like James Cameron, Peter Jackson, King Hu, John Woo, all the amazing journeyperson filmmakers who made the great kung fu and martial arts Hong Kong action pictures as members of this extended family.

You’re probably way ahead of me so I don’t want to gild the lily here. But just in case this sounds like so much bloviating (which it very well may be) without any substance, I’d like to spot analyze and string together a key sequence from a few of these key moviemakers to flesh out the thoughts.

Sergei Eisenstein, along with several other brilliant Russian moviemakers of the 1920’s (Pudovkin, Dovzhenko, etc) progressed the art of movie editing to a point rarely matched since. The classic example one sees in film school is Eisenstein’s “Odessa Steps” sequence in The Battleship Potemkin. Here an exultant crowd of Odessa citizens cheering on rebelling sailors at sea are disbursed by Czarist troops who ruthlessly bayonet, shoot, and trample anyone in their way.

Eisenstein uses a number of techniques that would ultimately be used most in action moviemaking but which, in this context, drive home the political point that the Czarist Troops are inhumane and the system corrupt. Eisenstein uses “overlapping” or “repeat” editing to elongate the citizen's’ flight down the steps so that a sequence that in reality would have probably taken one minute takes five minutes here. Eisenstein cross-cuts between several key characters so we understand the human fear, confusion, naivete. And most famously he follows a baby carriage that careens down the steps after the mother is killed past all the scenes of violence until the baby itself is killed at the bottom of the steps.

By making the editing “visible” and felt (rather than the American style which still pre-dominates to this day of working to make the editing “invisible”), Eisenstein causes the analytic part of our brains to fire, grapple with what we’re seeing. The edits themselves become thrilling.

Jean Luc Godard had the added bonus of sound in the 1960’s and thus was able to forge a montage of BOTH IMAGE + SOUND. This allowed Godard to create sonic dialectics as well as visual dialectics. Famously in Contempt (and other movies), Godard would use just four seconds or so from a music score repetitiously then suddenly drop out all sound. Or Godard would drop in diegetic natural production sound then drop it out so the film ran to just silence then he’d drop in the music score. The alternation of realism-silence-music would create an added editorial level of montage. Godard also introduced a number of “fourth wall breaking” techniques like repeating the same action from different angles, playing the same scene back to back to back, or adding self-aware narration commenting on the scene itself to create a level where the cinema itself was being interrogated. One of his most famous sequences-the “Dance” sequence in Bande a Part illustrates this pretty well:

In many ways these two moviemakers (Eisenstein and Goddard) were then synthesized in American moviemaker Martin Scorsese. Scorsese also drew inspiration from the pop music experimentation of avant garde moviemaker Kenneth Anger (Scorpio Rising) to use montage, pop music, varying film speeds to create editorial masterwork sequences.

Most famously still is Scorsese’s “Last Day as a Gangster” sequence from Goodfellas where we see Henry Hill’s last cocaine-fueled day as a gangster from Henry’s coked out perspective. Scorsese repeats the same shots twice (Henry flipping the meatballs and looking out into the hallway), uses snippets of pop music from Muddy Waters to the Rolling Stones to Harry Nilson to George Harrison, uses Eisensteinian techniques like overlapping editing, repeat editing, match cutting to create a musical rhythmic sequence that shows just how out of control Henry’s life has become.

Eisensteinian techniques like “repeated editing” crop up constantly in action movies. Famously, James Cameron used the technique a number of times in Terminator 2 to really accentuate certain stunts like the Terminator on a motorcycle diving into the LA River system. Spielberg has used the technique to heighten tension. Conspicuously in Raiders of the Lost Ark at the beginning when Indy is trying to climb up a vine to get through a closing stone door. When one watches the sequence, it’s clear the door is nearly shut in several shots but Spielberg cuts away and back to the shot and the door is suddenly a bit higher then it was to heighten tension.

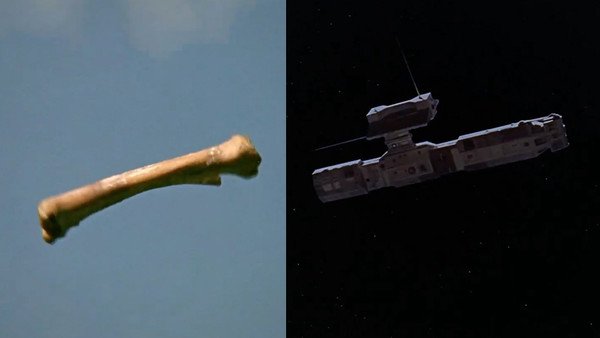

And then there are the famous Eisensteinian “match” cut moments (where SHOT A matches SHOT B in shape but not content) in Kubrick’s 2001 when a bone used as a weapon gets tossed by a primitive ape-man (SHOT A), comes down, and suddenly becomes (SHOT B) a space station in 2001.

David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia famously does a similar magic trick when Lawrence watches a match burn in his hands. When he blows it out (SHOT A) the film suddenly cuts to (SHOT B) a desert sunrise.

Of the three schools identified so far (Murnau, Lang, Eisenstein), the Eisenstein lineage is the one most in need of a new generation. Whether digital editing has made editing so easy that watercolors are getting produced instead of pain-staking egg tempuras (both have their merit) or because this kind of dialectic montage, like satire, is incredibly hard to pull off with felicity, it still feels like there’s a whole undiscovered country of dialectic montage yet to be traversed.

Please someone pack your bags. The journey awaits.

Craig Hammill is the founder.programmer of Secret Movie Club.