Stephanie Sack on Paul Verhoeven's THE FOURTH MAN (1983, Holland)

Released in 1983, Verhoeven's final film in Holland, The Fourth Man, stands as both a Eurohorror icon and a cinematic cipher. From religious psychosis to daydreams of death to a jewel-toned palette of murder, the film's highbrow Hitchcockian narrative is matched and arguably bested only by the outrageousness of its lysergic exposition. Crafted consciously to present as an arthouse award darling, this Dutch Giallo* is intentionally front-loaded with spiritual satire, structural sophistication, and color-saturated style.

Born in Holland in 1938, Verhoeven's childhood was profoundly affected by the traumas of wartime; referencing these indelibly memorable years in interviews, he recalls violent chiaroscuros of houses ablaze and shocking scenes of the dead lining the streets. These traumas, as with many other European filmmakers of his generation, informed the post-war problems and preoccupations so intentionally explored in his prolific directing career. A recipient of a PhD in Mathematics and Physics at the age of 22 from the University of Leiden, by the early 1960s he had all but abandoned this advanced degree, and instead focused on making films. This background in logical thinking and complex theory innately translated to his preternatural command of an astonishing handful of genres. His first film, a stylish 1960 black and white short, slyly explores women's shifting sexual identities as influenced by a Hitchcockian male gaze. By 1969, he had moved into television by helming an historically accurate 12 hour series about a 16th century swashbuckler starring a young Rutger Hauer. Even at this early stage of his filmmaking career, the liftoff between Verhoeven's ferocious intelligence and technical aptitude was evident.

By the time Verhoeven came to the preproduction of The Fourth Man in the early eighties, he had almost 25 years of art and craft from which to draw, despite a chronically lukewarm reception by Holland's film critics. Known primarily for his insistence on slick mise-en-scene and sexually-explicit storylines, Verhoeven's output had proven to be some of the most commercially profitable Dutch films in the seventies. Accused by Holland's cultural gatekeepers of creating characters who lacked depth and narratives without nuance, he was under palpable pressure to deliver something more critically acclaimed. Stung by the ongoing underestimation of his vision, Verhoeven decided to make a film specifically to combat these accusations.

Indeed, from the jump The Fourth Man is not f*@king around with horror imagery and Italian inference, particularly that surrounding our main character. Within the initial five minutes of the film, the magnetically disheveled alcoholic writer Gerard Reve has awoken in an attic cluttered with books and bibelot and Catholica, complete with an errant spider spinning her web on a statue of Jesus. He is hungover, gloriously so, and does not seem concerned whatsoever about his shaking hands, haggard appearance, or penile-friendly pantlessness. As he pulls himself together to deliver a lecture in a nearby town, he knocks over empty wine bottles while pouring himself a nip of the hair of the dog, toasting one of the many statuettes of Mary before tossing the shot of breakfast booze down his gullet. This is a man who DNGAF about his addiction, or ostensibly much of anything, but even in the throes of "delirium tremens" still respects the mother of God.

Soon, however, the depth of Gerard's powerful imagination and the breadth of his morbid fantasies are revealed when an argument about petty domestic frictions breaks out between him and his violin-practicing male companion. Young, blond, and cheekboney, this musical gent is not at all pleased with Gerard's boorish behavior, and rightly so. Looks are exchanged, escalating to a lover's quarrel, and then without preamble Gerard is viciously strangling Cheekbones with a tie, audible gasps and compressed gurgles now replacing the banal tones of the violin. Just as suddenly, Cheekbones is still sullenly playing his instrument and Gerard is about to huffily depart for his engagement. This graphic sequence of a shocking strangling, revealed to be the first of Gerard's many dark daydreams, introduces the film's haughty velocity of intermittent ambiguities and Giallo-esque psychedelic physics. A proudly self-proclamined practicing Catholic, Gerard's flippant ability to compartmentalize his homicidal homosexuality seems at odds with his publicaly stated religious convictions, although it is this and many other complicated moral incongruities which masterfully manifest the film's yawing ballast.

Indeed, while narrative even in their diversions, the expository visuals of color, light, and locale within these hallucinations are thrillingly redolent of Hitchcock's pacing, DePalma's cinematography, and Argento's artistry. Accordingly, it is the frequency of Gerard's demented reveries, violent hallucinations, and disturbed daydreams which arguably inform both the film's Giallo-esque direction and misdirection. Chromatically lascivious and effluvial with Eurohorror gore, Gerard's unreliable narration of seemingly commonplace situations increasingly slips into hyperreal surreality and flips back to "normal" just as seamlessly. While on his way to the speaking engagement, the hypnotic motion of a mundane train ride lulls him into another powerful nightmare, this time of discovering the glistening viscera of an enucleated eye oozing through a hotel room's peephole (of Room #4, no less). Within the same scene on the train, everyday details are jarringly infused with an electric palette of libidinal color, as a mysterious blond woman swathed in shades of sapphire blue cleans up the riotously ruby red splatter of spilled tomato juice. Later in the film, Gerard will again witness the florid trauma of wounded flesh just as he will again witness the woman in blue immersed in spatters of red, and, while both are immediately recognizable, neither are identified in the ways he initially envisions, adding to the film's expert exploration of uneasy ineffability.

Of course, no Giallo is complete without a mystery, although precisely what Gerard is trying to solve is equally as mysterious as his emotional locus. A surreptitious sieve of predatory sexual encounters and slippery psychological sparring disrupts Gerard's ability to confidently reconcile the incongruities of his own reality as he finds himself entangled with a woman who appears to have her own deceptive collection of evasive maneuvers. Dazzlingly Hitchcockian in her delicate blondness, openly armed with a woman's fleshly weaponry, and rapidly revealing a depth of darkness similar to Gerard's own, business owner and beautician Christine Hasslag is ostensibly the decider of the titular Fourth Man, having had three husbands who, in her presence, each met rather unseemly fates -- murder by misadventure, as it were. In this Black Widow, whose sexual appetites and reckless impulses are similar to his own, Gerard has found a receptacle, however immediately and inscrutably, for his own projections and problems. Curves clad in red, lips painted scarlet, smirks substituting for smiles, Christine self-assuredly owns her social presentation however licentious it might be; she drives like a maniac, f*@ks on the first date, and may or may not have murdered three men to whom she once pledged her eternal devotion. Marriage, the only vector through which sexual congress is approved by Catholicism, seems to be merely one of Christine's many manicured methods to ensnare sexually-motivated men into her murderous clutches.

Or is it?

Emblematic of Gialli's cinematic fascination with damaged women equally manipulative as they are beautiful, Christine serves as both the oracle and obstacle for Gerard's participation in the mystery. While a guest in her private apartment within her professional venue, Gerard is coddled and comforted with the coercions of womanly domesticity, yet he suffers through a series of vivid nightmares in which she emasculates him with a pair of stylist's scissors, a castrating angel out to coldly cut off his maculine potency. Her diffuse demeanor, however, cannot overcome the distilled terror of childhood trauma, and, in a scene that predates a similar plot point in 1987's Fatal Attraction, Christine's primal fears of abandonment and rejection are revealed when Gerard playfully pretends to drown. Her silhouette shifts from beach babe to bawling baby, her soft shoulders now slumped with the physical blow of anxiety, her patrician profile now contorted into shrieks of sorrow. Gone is the cool countenance, the unfazed courtesan, the naughty hostess. It is here where Gerard, unknowingly, sees Christine at her most vulnerable, and where her own emotional evasions and murky motivations are, however briefly, laid bare.

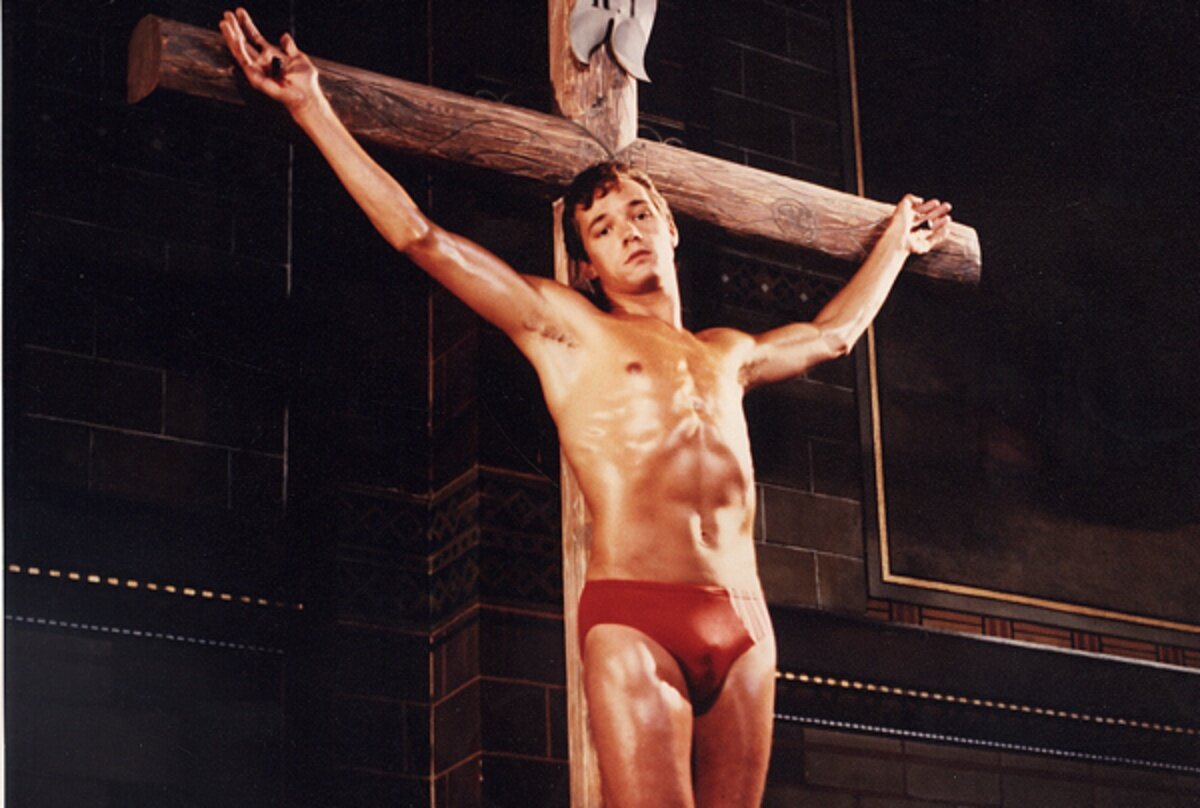

With both main characters hamstrung by their own fleshly distractions and psychological compulsions, two calling cards of classic Gialli, the final act of the film reveals the irresistible forces of sex and death colliding in the form of two attractive and damaged people: more sex and more death. Gerard hallucinates a crucified twink complete with a throbbing erection; Christine's private collection of essentially snuff films are shockingly revealed; and Mary the Holy Mother of God Herself is somehow employed as a kindly nurse at a mental hospital. Typical of canonical Gialli, there is a gloriously fatal stabbing of an eye, albeit with a hyperphallic weapon heretofore unreplicated in all of Eurohorror.

Referred to by Verheoven himself as the spiritual prequel to his infamous erotic thriller (erotic thriller = American Giallo) Basic Instinct, The Fourth Man benefits from repeated viewings through any number of lights and lenses. As the final film in Verhoeven's Dutch output, it caps a fine if confined career; as self-conscious arthouse satire it more than succeeds. However, it is as a neon-drenched descendant of Hitchcock, as all canonical Gialli are, where The Fourth Man more than academically earns its place as a deliciously dark and demented Dutch Giallo.

Written by Stephanie Sack.

https://www.facebook.com/stephanie.sack.5/

https://www.instagram.com/voluptuousrobot/

Check out this post and Stephanie’s blog: https://wearepolaris.org/