Problems, Problems, Problems: How do we re-introduce complexity into cinematic conversations? by Craig Hammill

One of the problems a film programmer runs into again and again these days (though thankfully not as often as you would think) is how to handle problematic films and filmmakers.

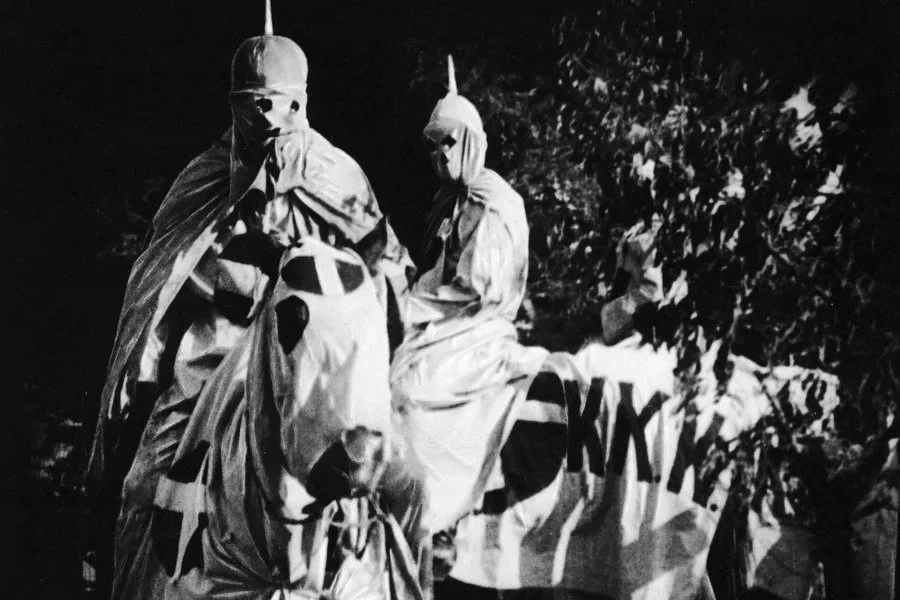

The reasons for this are probably known to anyone reading this article. A movie like 1939’s Gone with the Wind (dir by Victor Fleming, produced by David O Selznick, MGM) which was once a classic staple of almost any film festival, retrospective of Hollywood’s annus mirabilis, discussion of the greatest movies ever made by the Hollywood system, is now often avoided because of its extremely dated and problematic takes on race, the Civil War, its representation of the Confederacy, etc.

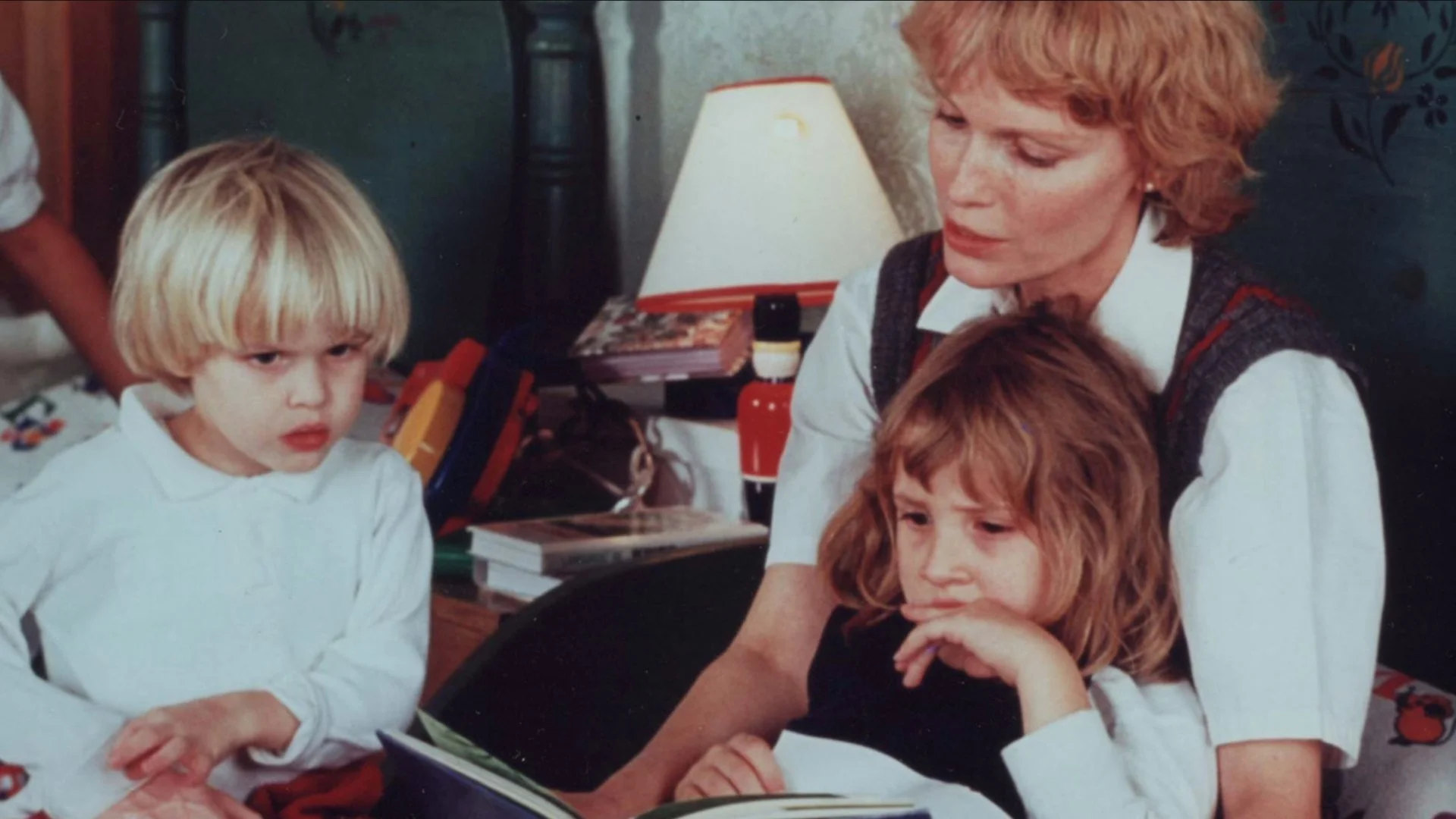

Filmmakers like Woody Allen and Roman Polanski become more and more problematic to program. But for different reasons (which shouldn’t be conflated). Allen remains mired in child abuse allegations of his adopted daughter, Dylan Farrow. Dylan persuasively and earnestly maintains these allegations to this day. And her allegations deserve credence. The problem is that Allen was cleared of these allegations a number of times, submitted himself to multiple investigative panels who also cleared him, and always makes public statements categorically denying them. But after so many years, decades, centuries, eons of powerful men escaping justice and victims being ignored or dismissed, this particular case proves difficult for all involved. Including film programmers.

Polanksi was found guilty of drugging and sleeping with a 13 year old in the early 1970’s. He fled to Europe shortly thereafter. Since that time, numerous other underage women have come forth with stories of Polanksi engaging in similar behavior. Polanksi himself even admitted this behavior (in a self-justifying way) in his autobiography where he claimed such things are viewed differently in Europe than in the United States.

And while these are several of the most high profile examples of problematic movies and moviemakers, there is a growing list of movies and artists. . . even production companies. . .that prove tricky and thorny for a film programmer. We just have to name Lars Von Trier, Dave Chapelle, Bill Cosby, Michael Jackson, Louis CK, Brett Ratner, Scott Rudin, Aziz Ansari, Bill Murray, anything from the Weinstein Company or Miramax, early movies like D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation or Leni Refinstahl’s The Triumph of the Will to get a sense of some of the challenges.

The problem, at least as this programmer sees it, is that it feels as if we have a tendency to treat all these different movies, films, filmmakers, cases, the same. To lump them into one big category of “problematic” and just avoid engaging, dealing with the different specifics because it’s too complicated, the current environment is just too intense, etc. And that’s to the detriment of complex conversation and understanding.

The goal of this short article isn’t to propose some kind of catch-all solution or approach. This issue is too thorny to have an easy solution. But it is to suggest that we might be able to steer the direction of the cinematic ship towards a better north star if we at least begin to engage in conversation, discussion, examination of how to contextualize problematic movies and moviemakers in the current and future environments.

Since we started in 2016, we’ve engaged on this topic several times in forums, debates, discussions. And a number of fairly interesting points have been repeatedly raised.

One point is that ultimately, the adult movie watching public has to be trusted to be just that…adult. If a film programmer or rep company feels a movie has merit AND they’ve done their due diligence understanding what the fallout/reaction might be for programming something controversial, they then program it at their own risk and trust the audience to make their own decisions about whether to attend or not. And to understand that the complex issue of “the art versus the artist” is an eternal one.

Another point is that it’s equally problematic to stop screening certain movies because of the behavior of a single collaborator. One female movie editor interestingly pointed out to us that when a movie gets taken out of circulation, one is not just punishing or censuring the problematic filmmaker but everyone else who worked on that movie in good faith: the cinematographer, the editor, the actors, the crew, the writer, the composer, etc. Many times hundreds of people worked and contributed their own voice to a story/script they believed in, unaware of one of their fellow collaborators’ questionable behavior.

“When you take that movie out of circulation,” she said. “You’re telling me my contribution doesn’t matter.”

On the other hand, it’s equally irresponsible to pretend that important issues of representation, inclusivity, new appraisals/evaluations that take into account often ignored or historically silenced viewpoints, sensitivity, a rightly changing and progressing climate, can be ignored in the name of “art”.

Often this feels like an excuse by older or entitled or powerful or majority enjoying folks to not evolve or even try to understand the concerns/viewpoints of the new movements, generations, identities.

So. . .finally we arrive at the nub of the issue: is there a kind of “golden mean” approach where movies and moviemakers can be shown because the movies and/or moviemakers still have clear important merit while acknowledging the very real issues surrounding the work?

Can a complex conversation be kindled?

Can the very important democratic value of allowing work to be debated in a free and open society in the market of public opinion be balanced with the equally important value of acknowledging that oppressive or dismissive or problematic behavior and viewpoints of the entitled majority have too often gone unchecked, unchallenged, unquestioned?

Is there a way to reintroduce complexity into the discussion? Is there a way to somehow create an environment where folks feel comfortable enough to speak out, to attend, to debate? To feel comfortable and supported enough in an environment of good faith to feel they can discuss, make a mistake, share a viewpoint, and not immediately be attacked?

This programmer’s gut sense is that YES there is a way to do all these things. Like many things, it’s probably most helpful to do these things incrementally. To work in partnership with the audience. To be sensitive to the very good points folks on different sides of issues will have. And to truly be open minded that there may be a more complex way to see something.

It is very likely that we are in the middle of one of those societal growing pain spasms that have occasionally rocked human history. When Johannes Gutenberg invented the printing press in 1440, there was an extended period where con artists took advantage of the ability to print something like the Bible, which heretofore was only available in Latin to an educated, rarefied literate class, in working class peoples’ native tongue but. . .to pervert/mistranslate passages for their own purposes (a practice that sadly continues to this day across all media).

In this age of instantaneous, amplified reaction via social media platforms to anything happening in the world, we may be living through a similar period where the perceived majority opinion on something isn’t even the factual majority opinion at all. But rather the LOUDEST, MOST AMPLIFIED opinion which gets mistaken as the majority position. Because it’s LOUD.

It’s also very hard to communicate complexity these days. Or even leave a door open for complexity. A recent case in point might be the series of Dave Chapelle’s comedy specials on Netflix ending with his most controversial The Closer. Chapelle has now developed a reputation in some circles (though it’s being vigorously debated) as being “transphobic” or unfairly going after the transgender community in his act, which, when one actually listens to the routines isn’t exactly what he’s doing.

The interesting thing when one listens to the routines themselves is that Chapelle is actually making a very different point altogether. One he keeps trying to underline: that he supports the LGBTQ community, that he’s an ally, but that black folks have been struggling for equality and equal treatment for four hundred plus years in this country and still don’t receive it. And that he’d appreciate if the white community, whether LGBTQ or not, would acknowledge this distinction in minority struggle. His argument is always aimed at the white community. A point he makes interestingly where he illustrates the different reactions a white member of the LGBTQ community might have to calling the cops than a black member of the LGBTQ community.

Chapelle certainly doesn’t help himself with his increasingly growing sense of self-importance and defensiveness in his routines. And it’s a bit baffling how folks like Chapelle or author J.K. Rowling can be so generationally tone-deaf to the trans community’s critical arguments that at this moment in time they need supportive, empathetic allies in their own struggle to have a level playing field in existence.

But maybe it goes back to the anchoring possibility that neither side is giving benefit of the doubt to the other. We all seem to get very emotional, very defensive, very unwilling to even consider the complexity of a point of view we’ve decided is wrong, very quickly.

If all sides keep going in this direction, the clay on the potter’s wheel that is the American experiment is just going to fly off and splatter the walls.

If we want to keep that clay on the wheel so that it can continue to evolve into something, we need all hands to be steady and to be working together.

The American experiment of freedom of speech, freedom of religious (or non religious) belief, equality of all peoples is too important to die because we all couldn’t be bothered to make a good faith effort to re-calibrate our approach to difficult cultural and societal issues that will always rock a multi-cultural, diverse society like America.

Anyway, this is not a topic that is going to get resolved in a blog or even a thousand blogs. But it is one that should be engaged with more than it is right now.

This programmer feels one of the key aspects of film writing going forward will be to find a way to engage head on with difficult topics. But in a truly humble and respectful way where folks on all sides will feel such writing was done in good faith. And with the willingness to correct or even change a viewpoint because good faith discussion was stimulated.

Maybe if the film community feels this tone, the level of dialogue will change and complexity can return to our discourse and to our cinema.

Craig Hammill is the founder.programmer of Secret Movie Club.