MOVIE MUSICALITY by Craig Hammill

“A good structure for a screenplay is that of the symphony, with its three or four movements and different tempos.” Akira Kurosawa

I’ve heard many directors ultimately say that while cinema is cinema, if it’s close to any other art form it’s most likely music.

This has always been interesting and instructive to me. An initial reaction might be to think cinema is most related to the novel or to the theater or even to opera. And of course, cinema takes from and is inspired by all these art forms and more (radio, painting, sculpture, dance, architecture, design, to name just a few).

But somewhere in my twenties (I think, maybe it was my early thirties, man time moves fast. . .), I came to feel that movies are most like music and dreams.

A great movie often has a dynamite story. But it’s the way that story is told with the camera, performance, editing, and sound that moves us.

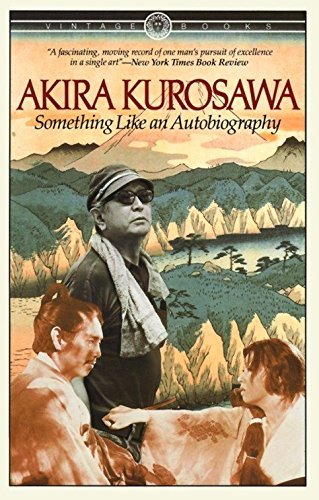

Before I get too abstract or nerdy, let’s drill down on what Akira Kurosawa said at the start here. Once I read Mr. Kurosawa’s amazing autobiography Something Like an Autobiography (definitely read it asap, best director autobiography ever written):

which contains 20 or so pages of direct advice to moviemakers at the end, I started listening to symphonies based on the quote above.

My favorite is most likely Beethoven’s 7th (check it out here):

It’s not as instantly recognizable as the 5th or the 9th but in many ways it’s the most sublime, layered, and fascinating.

A symphony has four movements. Usually the first movement introduces the themes of the symphony in infancy (they often get fully developed in the 4th movement). The second movement often provides a contrast to the first. I’ve noticed many times this is the slow movement. Much like a rock or pop album will put its ballad as track #4 (before the days of iTunes and Spotify) after a few kick-ass uptempo songs, the second movement slows things down. The third movement often complicates everything from the 1st and the 2nd while possibly introducing new themes. And the 4th movement then brings everything to full expression in a kind of climax.

One of the greatest examples of the symphonic structure in film occurs in Mr. Kurosawa’s own Seven Samurai. If you think about the movie, you actually note the movements:

Kurosawa cleverly introduces both the wisest Samurai Kambei and the most foolish Kikuchiyo in one scene in the first movement.

1st Movement: The Bandits vow to attack the village in 40 days when the barley is ripe, the village decides to get samurai to defend it, the farmers go to the city to find samurai, the seven samurai, each with different characters, are found and decide to take on the job even though it has no pay or glory. End of 1st Movement-all the themes of the movie have been introduced in their infancy.

As the Villagers and Samurai prepare in the 2nd Movement, Kurosawa finds ways to introduce, complicate, and develop individual relationships like the forbidden romance between the Young Samurai and the Young Villager enthralled with the idea of being with a Samurai.

2nd Movement: The Samurai arrive at the village. The Villagers fear the Samurai. Kikuchiyo (the rebellious misfit pseudo samurai played by Toshiro Mifune) somehow knows how to get the Villagers to trust the Samurai. The Samurai train the villagers and prep the village for the attack. The Samurai learn about each other and develop relationships with the Farmers. When some Farmers rebel because their houses will be sacrificed, lead samurai Kambei (Takashi Shimura) chases them down with a sword, and explains everyone has to unite and accept some sacrifice or the whole village will be destroyed. Slowly the Village gets ready for the attack. End of 2nd Movement. The preparation, planning.

The death of the first Samurai in the 3rd movement signals that everything is coming to an unavoidable confrontation.

3rd Movement: The Samurai decide they must attack the Bandit’s hideout first to thin out the Bandits numbers. The attack costs the life of one Samurai due to a revealed secret of a farmer. The Bandits attack the village and are repulsed. All the relationships and motivations change and complicate now that the battle is upon the village. Decisions are made that cost more lives of farmers and villagers and cause great stress and shame. End of 3rd Movement. Themes are complicated and developed. New themes are revealed.

The Final Battle in the rain while temporally short in comparison with the rest of the movie (5-10mns tops) achieves a kind of climactic culmination and full expression of all themes developed from the beginning.

4th Movement: The Samurai and Villagers know the final battle will occur the following morning. They spend the evening trying to prepare. Final decisions are made that change the lives of both villagers and samurai. The next morning all prepare for the final battle which will occur in a thunderous rainstorm. The Samurai and Villagers fight the Bandits and narrowly win though they lose many of their own including some of the most beloved samurai. Several days later as the Farmers go back to planting and no longer need the remaining Samurai, the remaining Samurai evaluate the costs of the battle and the complicated nature of both humans and existence. End of 4th Movement which here also includes a kind of coda with the final scene.

But movie musicality goes beyond structure. Editing is musical. One of the greatest examples of how cinema is sequences and sequences are cinematic music might be Martin Scorsese’s “Last Day as a Gangster” sequence in Goodfellas where the coked up, coming attractions trailer editing reaches a fever pitch we know can’t be sustained:

Or another kind of musicality can occur in shot composition and selection itself. Take this incredible sequence from John Ford’s Stagecoach where the lighting and shot selection all lead to a breathtaking chiarascuro shot in a hallway that expresses the feelings of two characters and their own nature better than any dialogue ever could:

Watch from minute 47 through minute 51 for the full STAGECOACH sequence.

Movie musicality in sequences also creates a kind of “melody and harmony” when one cross cuts to create ironic meaning. Fritz Lang and Jean Renoir in the early 30’s were masters of this kind of contrapuntal ironic narrative sequence. Check out this hilarious AND disturbing sequence from Renoir’s La Chienne where a murder is cross cut with a puppet show:

And one could go on and on and on. But on some level, cinema and movies, like music and dreams, affect us on a very profound level, tight rope walking between the conscious and subconscious.

When movies don’t have musicality they can still be great but they will feel prosaic (like reading a great if straightforward news article about a world event). When movies have that cinematic musicality they become a kind of dream poetry that stimulates multiple thoughts, inspirations, emotions, feelings in the view simultaneously.

As we pass through the middle of our March Musical Madness series, I realized that possibly I personally love musicals so much because they are a kind of strange “literal” acknowledgement of the connection between cinema and music. When people break out into song and dance, it’s a kind of spontaneous communal human poetry.

Anyway, here’s to cinema and music. May filmmakers continue to be intoxicated and find original exciting expression in the combination of both.

Craig Hammill is the founder.programmer of Secret Movie Club.