MIXED MESSAGES: Rossellini's powerful, strange, comedic THE FLOWERS OF ST. FRANCIS (1950, 89mns, Italy)

It’s instructive when you see a movie you don’t get upon first screening but sense is profound.

Such is the case for this writer with Roberto Rossellini’s (and Federico Fellini’s co-scripted) THE FLOWERS OF ST. FRANCIS (1950, Italy).

The movie is based on two well-known 14th century Italian novels Fioretti di San Francesco (The Little Flowers of St. Francis) and La Vita di Frate Ginepro (The Life of Brother Juniper) which tell now popular folktales, parables, stories about the beloved humble Italian Christian monk Francis of Assissi and the fellow monks who followed him and likewise took vows of poverty and service to others.

Francis is known to many Christians as the Saint who loved nature, talked to animals as equals, and, like Buddha, gave up a life of wealth to live a life of service in the most humble of conditions. When the current Pope (born Jorge Mario Bergoglio) took his papal name, he choose that of Francis.

The opening chapter finds Francis and his fellow monks in a rainstorm and sharing their humble shelter with an angry farmer and his animals.

Rossellini’s movie focuses on 9 of the 78 stories from the beloved Italian classic (the flowers refer to the little stories/parables themselves). What makes the movie so fascinating is its subtle, multi-layered tone. Master Italian moviemaker Federico Fellini is the co-screenwriter (very early in his career, 1950 is the same year he started directing). And Fellini’s unmistakeable impish sense of humor courses throughout. So much so, one occasionally feels as if they are watching a Fellini movie.

Rossellini, known for his neo-realist masterpiece World War II trilogy Rome Open City, Paisa, and Germany Year Zero and for his 1950’s intense collaborations with his then wife Ingrid Bergman WAS NOT known for comedy.

So the shift in tones within the movie chapter to chapter, even within one story itself can sometimes cause minor whiplash.

The movie is filled with quiet humor. As an audience member, you sometimes wonder if these Franciscan monks were actually competent and effective. Or if, as the movie sometimes seems to imply, they were well intentioned but naive holy fools. At times, the movie seems to say they were both.

Some chapters are quite short yet funny. In one, a grumpy elderly man suddenly shows up at the monks’ humble abode. His family feels he has dementia and wants to be rid of him. The Old Man declares he wants to follow Francis. Francis immediately accepts him into the order even though we get the feeling the Old Man is going to be a handful (which he is for the rest of the movie).

One particular chapter in which Francis is repulsed then tries to comfort a wandering leper plays almost as horror (the makeup for the leper is shocking, effective, and graphic) at the same time it’s profoundly moving.

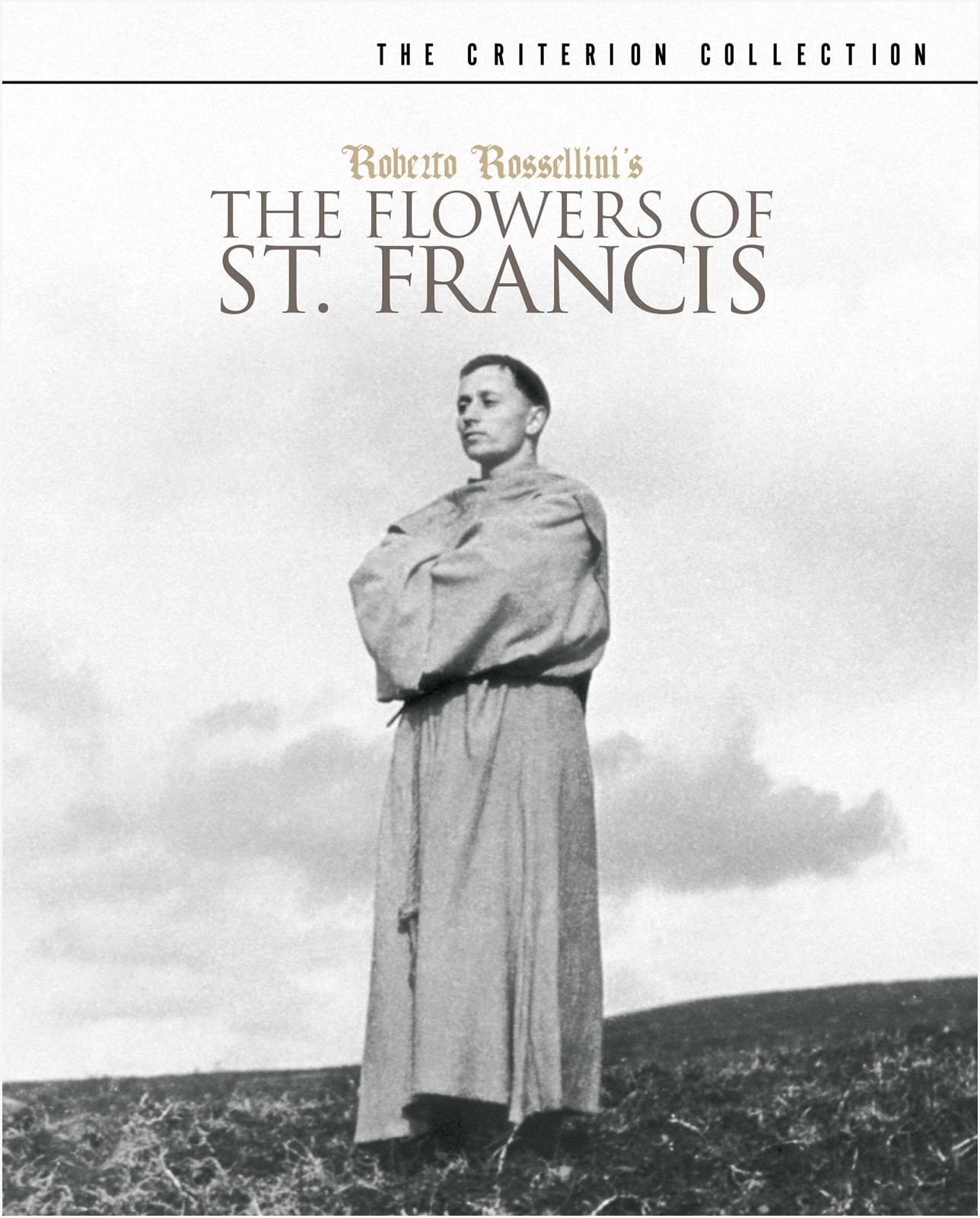

This still captures the mix of tones. Tyrant Nikolai (played by famed Italian actor Aldo Fabrizi) goes BIG. While the actual overall tone of the movie leans more towards a quiet comic neoralism.

It’s also hard to know whether a movielover is armchair quarterbacking since we now know that Fellini would shortly go on to become one of the most beloved and well-known world cinema figures of all time. But it does sometimes feel as if there are competing sensibilities in the picture: Rossellini may have been inclined to be more intense, serious, focused. Fellini may have been drawn to the rich, beautiful, human comedy and contradictions of flawed human beings, sometimes inept, trying to develop a workable method on earth to do service to God. This viewer, at least, felt the clash of sensibilities. An extended chapter where the clownish Father Juniper is alternately tortured, threatened with death, and inspected by a tyrannical warrior named Nikolai (played by the biggest actual Italian actor in the cast, Aldo Fabrizi) and his brutish hordes is a marvel of tonal shifts. The chapter lurches from picaresque to grotesque to holy and reverent as if we’re about to watch a martyrdom to wildly clownish and comedic to devastating. It’s as if Robert Bresson and Federico Fellini tried to co-direct a movie together.

Though Rossellini, Fellini, and many other Italian moviemakers who started in the neo-realist period would move past that kind of filmmaking to other styles, approaches in the 1950’s, neo-realism does inform much of The Flowers of St. Francis. Most notably in the casting where actual Franciscan monks play the roles of St. Francis and his followers. But also in the film’s simple yet beautiful cinematographic approach.

For all this, The Flowers of St. Francis has an unshakeable thematic core it returns to again and again. And this is what sticks with you. Whatever we think about the methods or efficacy of these humane comic monks, we never doubt their sincerity, their piety, their spiritual faith, their desire to truly live humbly and provide service to the poor, the ignored, the forgotten.

Francis often gave sermons to animals and referred to elements of nature as if they were friends like “Brother Moon and Sister Sun”. . .

When the final chapter arrives and Francis instructs his brothers to each go their own way to preach (by twirling until they get dizzy then heading in the direction that they fell), we feel a sense of melancholy and bittersweet wistfulness as we realize this sweet little movie is coming to an end.

These monks were funny to be with for 90 minutes and our hearts warmed to them. We also find we have developed a quiet respect for Francis’s patience and humility.

Maybe, this quiet surprising humble feeling that stirs in our hearts was the hoped for emotion all along. It’s hard to capture humility and quiet determination.

It’s a strange, compelling, comic, episodic movie. Yet it’s one that this viewer senses will stick with him. And it does so by never insisting on its own importance. But rather welcoming you in with a hug and a smile and a humility that seems modeled after the sweetness of Francis’s own approach.

Craig Hammill is the founder.progarmmer of Secret Movie Club