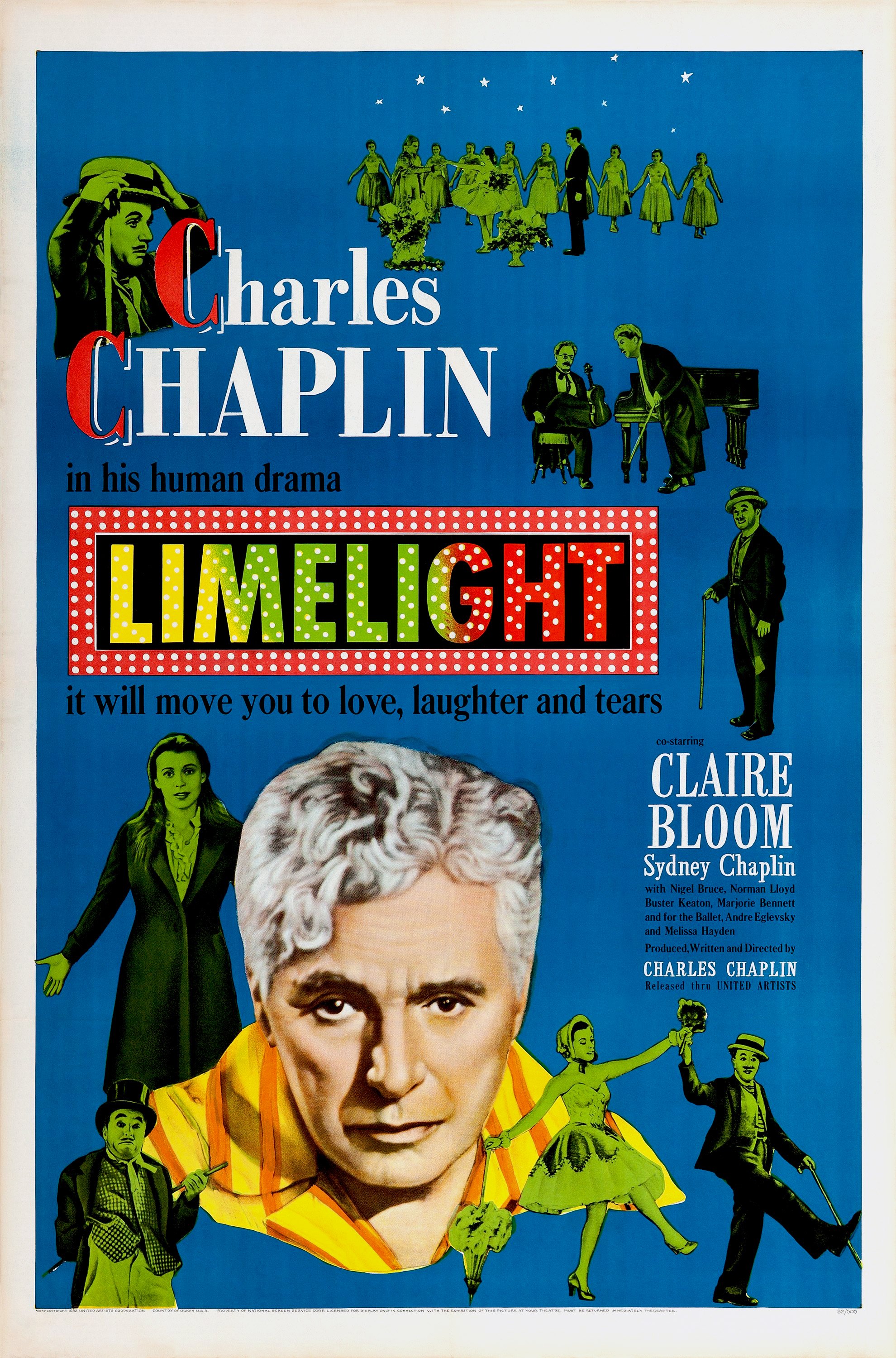

Limelight (1952, dir. Charlie Chaplin, US) by Patrick McElroy

There are changes and transitions throughout film industry that some of the directors that work in it smoothly adapt to, while others fall from grace. One of the biggest transitions in film history was the transition to sound, and one of the filmmakers who had the most difficulty was Charlie Chaplin.

Throughout the 1930s he refused to talk on screen, making two silent masterpieces, City Lights and Modern Times. He would eventually speak on screen with his 1940 satire The Great Dictator, and his 1946 dark comedy Monsieur Verdoux. While those films are regarded as classics now, they weren’t quite as warmly received in their time. My personal favorite of all of his sound films is the bittersweet 1952 dramedy Limelight, which turns 70 this month.

The film takes place in London in 1914 as WWI is about to begin, and Chaplin plays Calvero, a washed up stage clown. Calvero notices smoke one evening before entering his apartment, and discovers it’s one of his neighbors. He goes to the door to save a young woman from suicide – the young woman is Terry, a dancer played by Claire Bloom. The rest of the film consists of Calvero reminiscing about his past life, and how he tries to give Terry hope. He has to let go of his past to then go forward.

The movie was one of Chaplin’s most personal works. Like Calvero, he was apart of a past tradition – for Calvero stage performance was replaced by movies, and for Chaplin his physical schtick was replaced by verbal wit. So Chaplin, like Calvero, has to come to terms with not being what he once was.

Stanley Kubrick once said, “Chaplin is all content and little form. Nobody could have shot a film in a more pedestrian way than Chaplin.” In Limelight he doesn’t rely on show, but instead turns to body language, and simplicity, making something poetic and emotional.

Later in the film, there’s an appearance by Chaplin’s silent comedy rival, where they share the screen performing on a stage, and it’s both magical and sad, seeing two artists who were once at the top, come together once and do what was a past tradition.

When the movie came out, it wasn’t a success in the United States, because many were against Chaplin for complex political and personal reasons, but it would gain a cult following. People would see it as a late career film, where the director has advanced in wisdom, similar to John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in America, Akira Kurosawa’s Ran, John Huston’s The Dead, and Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman. As a writer you’re supposed to avoid clichés such as “I laughed I cried”, but if you are interested in the artists complicated personal life, Limelight is a film that will make you experience both emotions.

Patrick McElroy is a movie writer and movie lover based in Los Angeles. Check out his other writing at: https://www.facebook.com/patrick.mcelroy.3726 or his IG: @mcelroy.patrick