John Ford Chapters 11 & 12: The Masterpieces Pts 1 & 2

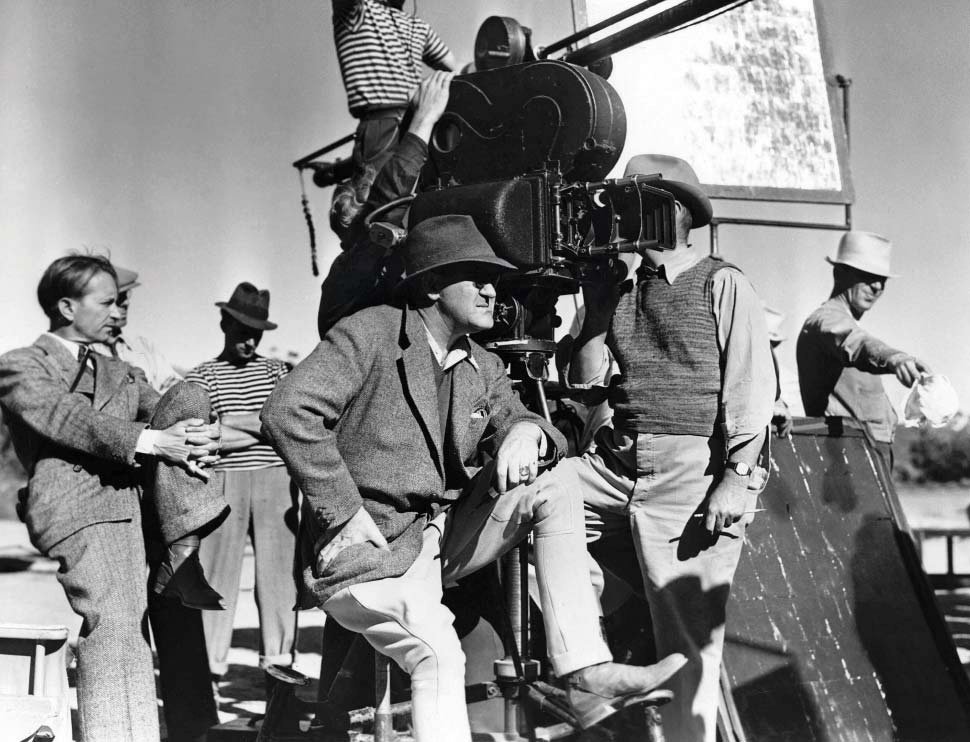

As part of our The Ford Fundamentals: John Ford Director of 2022 series, founder.programmer Craig Hammill is writing an appreciation in 12 chapters, a prologue, and an epilogue across the year.

Important Note: Movies will be talked about in depth so definitely spoilers!

CHAPTER 11: The Masterpieces Part 1-My Darling Clementine, How Green Was My Valley, The Quiet Man, The Searchers

John Ford’s My Darling Clementine, How Green Was My Valley, The Quiet Man, and The Searchers are routinely included in most Ford-o-files lists of his greatest masterpieces. It’s a testament to the Old Man’s powers that within a roughly 22 year time span (from 1939’s Young Mr. Lincoln through 1961’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance), he made arguably 12 masterpieces. Or put another way: Ford produced an all-time classsic American film every two years.

John Ford is considered the greatest director in the world, or one of the greatest, by among others, Orson Welles, Ingmar Bergman, Federico Fellini, Akira Kurosawa, Steven Spielberg, and Martin Scorsese. Ford is a director’s director: a filmmaker who somehow managed to navigate the treacheries of Hollywood for six decades, direct over 150 feature films, and make dozens of deeply personal, poetic, idiosynchratic pictures that bear his unmistakeable authorial stamp. Even more, Ford was one of those rare filmmakers who, while being known mainly for his Westerns, was able to make truly great movies in almost every genre.

If there is a thread that one can follow through the out and out masterpieces it is that at his best, Ford was able to harmonize his contradictions, talents, obsessions into feature length cinematic poetic symphonies.

It is the Ford movie your grandparent is often talking about when they say “They just don’t make ‘em like that anymore.”

Take a picture like Ford’s first after World War II-My Darling Clementine (1946). Ford’s take on the Wyatt Earp-Doc Holliday, Fight at the OK Corral is somehow both celebratory and elegiac. Full of Sunday morning daylight and nocturnal gaslight and shadows. My Darling Clementine is both a joyous hymn and a melancholic song sung at a wake. It’s fascinating to watch a movie that essentially uses the death or murder of lovers or family as its opening sequence (the death of Wyatt’s younger brother at the hands of the Clantons), its second act curtain (the death of Chihuahua, the defiant prostitute who loves and ultimately sacrifices for Doc Holliday) and its finale (the decimation of almost the entire Clanton family by the Earps).

It’s also a near noir Western in that it takes place almost completely at night. This choice heightens and throws into relief the one joyous sequence in the middle of the picture when Wyatt Earp bides the time by balancing on a wood beam before going to a dance on the foundation of a church about to be raised. The symbolism of how America is born (on the foundation of violence, vice, faith, and hard work) was so powerful that even the likes of 70’s auteur Robert Altman was unable to resist lifting the imagery for his McCabe and Mrs. Miller.

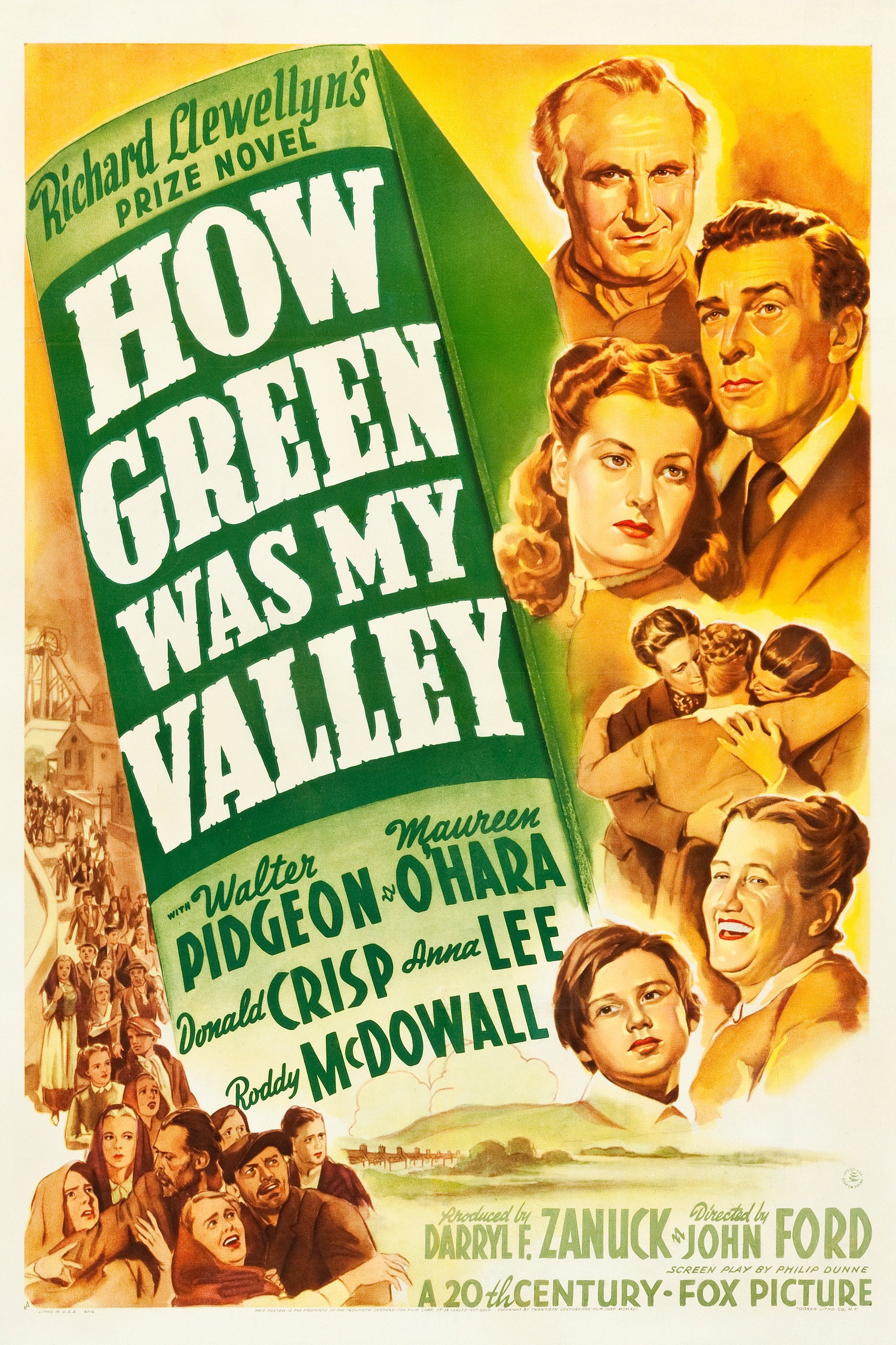

In Ford’s last picture before World War II, his Welsh mining family classic How Green Was My Valley (1941), Ford directs one of his most singularly poetic movies of his entire career. Once you’ve seen the movie a few times, you begin to realize it operates on a kind of poetic dream logic time. Huw Morgan, the movie’s young central character, observes the dissolution of his family by the unstoppable forces of fate, time, civic and social unrest, unrequited love. But the way he relates his memories makes one feel that years most have passed yet the entire time he is played by twelve year old Roddy McDowall. Also events appear to happen in single days that must have occurred across months or even years. Far from confusing the audience, this timeless or time-bending approach actually replicates our processes of memory more accurately. For in our memories, do we really see ourselves aging? Or do we often see ourselves (if in an illusory way) as the fixed point around which the rotations of other lives pass? How Green Was My Valley also includes a number of all-time great Ford sequences including Maureen O Hara’s mournful marriage to a man she doesn’t love while the man she does love watches her leave in the background shadows and a final “curtain call” in which characters who have died or disappeared return one last time so the family can reunite and take its bow.

Ford’s 1952 Irish-American dream of Ireland The Quiet Man at first appears to work because it’s a fairy tale about the mother country. But the more I watch this movie (one of my all-time favorites), the more I realize it works because it is really about a kind of dream of finding a home and community where one can bury one’s demons and live in a kind of timeless goodwill towards all people.

Yes, this will never happen. But maybe that’s the point. We still need that north star as a kind of fixed point by which we set our compass as we trudge through the treacherous swamps of reality.

But pulling back from getting too ethereal, The Quiet Man also attains all-time great status because it is one of the rare love stories in which both the female and male romantic counterparts TRULY feel equal and weighted with equal needs, wants, desires, dreams. To some extent, the American ideal of romance is one where two willfully independent people nevertheless find a way to come together to start family, to build something. Ford was never able to fully find that solace in his own life (though he did remain married to the same woman, Mary Ford, until the day he died). But The Quiet Man shows how he wish it could be.

Ford also made The Quiet Man as a kind of summation movie, not quite sure of his standing in the rapidly changing Hollywood landscape of the 1950’s. As such, it is filled with a kind of cinematic joy in which even Ford outdid himself. This is the HAPPIEST John Ford movie by several miles.

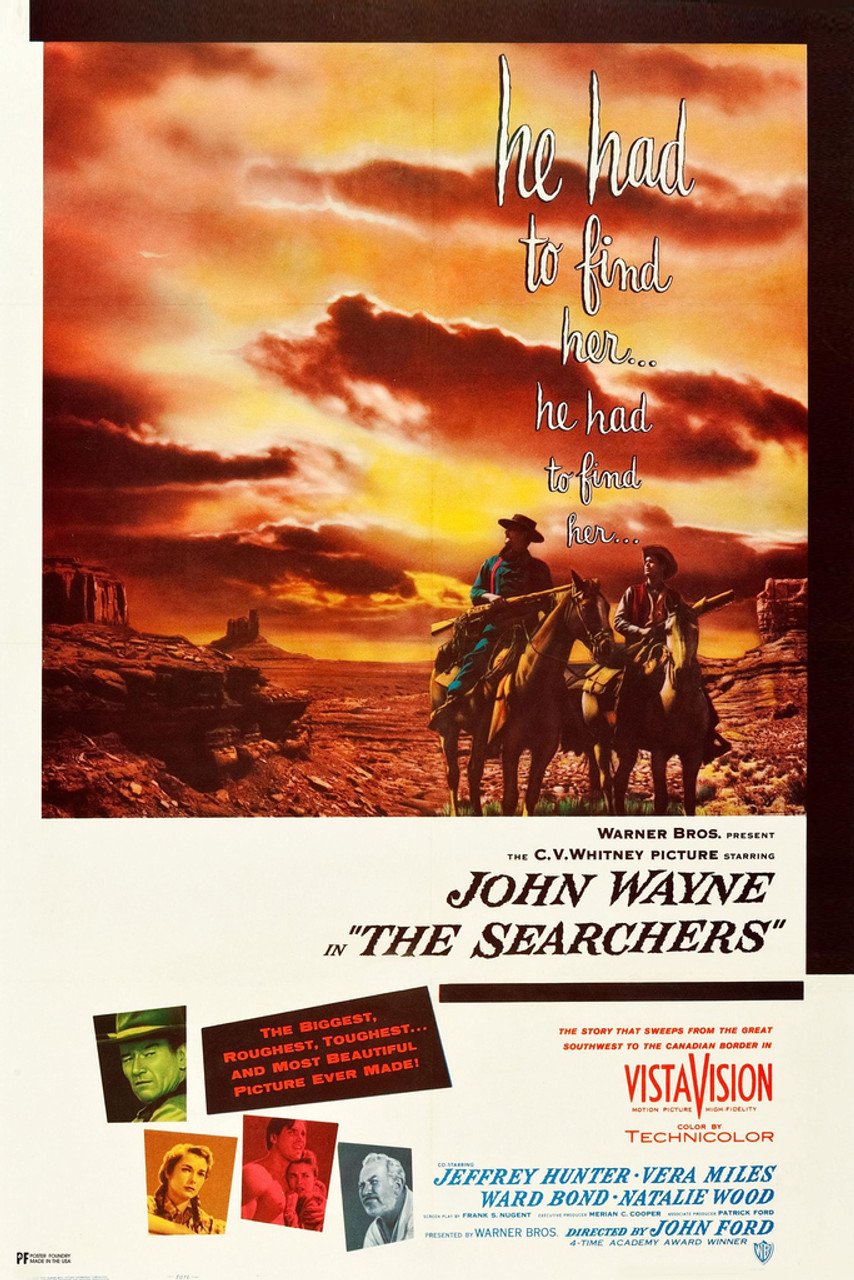

A few years later, Ford would suffer one of his worst public humiliations when he would begin drinking on the set of Mr. Roberts (something Ford almost never did), argue with its star and his long-time collaborator Henry Fonda, and ultimately leave the project to be finished by two other directors. At this low point, Ford was determined to immediately reprove himself. And he did so by making what many argue is his greatest film: The Searchers (1956).

To this day, The Searchers is one of Ford’s most inscrutable movies. It tells the tale of misfit Confederate veteran, virulent racist, and probable outlaw Ethan Edwards (John Wayne) who goes on a five year quest to find his niece after she’s abducted by Native Americans who also have wiped out Ethan’s brother’s family.

The Searchers has been praised and criticized in equal measure for its near impossible to pin sympathies. Does the movie see Ethan as a hero? Or as a disturbed man crazed and possessed with the lie that vengeance will somehow redeem his own lost life? Or both? It’s hard to argue the movie is unaware of Ethan’s evident psychosis. Ethan’s nephew Martin (Jeffrey Hunter) who is a quarter Cherokee is routinely shown as the clearly more level-headed and open minded of the two. In fact Martin explicitly states he is accompanying Ethan on his search to prevent Ethan from doing something murderous and violent. Is Ethan an anti-hero? Yes but we do admire his singular pursuit at the same time we fear that his search has curdled into a psychotic desire to kill Debbie for fear that she’s turned “Injun”.

Watching the movie repeatedly doesn’t resolve these tensions. It only heightens them. While Ethan is clearly shown to be a racist misfit who condemns himself to a life outside the family, he is also shown as a strong clever American character who won’t be scared or dissuaded by anyone.

In other words, Ethan Edwards represents both the BEST and the WORST of the American character. And, as a result, represents America’s own near psychotic identity crisis with itself.

If The Searchers does ultimately end on a note of reconciliation and grace it also ends with the reminder that something in existence prevents us from fully returning to the kind of innocent embrace of family we yearn for. All of us make mistakes in this life and all of us, to one extent or another, will be made to walk between the winds for a time.

We’ve already written about several of Ford’s other out and out masterpieces throughout the year (check earlier chapters!) Young Mr. Lincoln, The Grapes of Wrath, The Last Hurrah, Wagonmaster, Fort Apache, and Rio Grande. But we’ve saved this writer’s personal favorite John Ford movie for our last full chapter.

CHAPTER 12: The Masterpieces Part 2-Stagecoach

This writer’s personal favorite Fords are Three Bad Men, The Lost Patrol, Dr. Bull, The Informer, Young Mr. Lincoln, Stagecoach, The Grapes of Wrath, How Green was My Valley, My Darling Clementine, Fort Apache, Wagonmaster, Rio Grande, The Quiet Man, The Searchers, The Last Hurrah, and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. And in the end, the Ford closest to my heart remains Stagecoach.

Orson Welles watched just one movie forty plus times to prepare for Citizen Kane. . .forty times: John Ford’s Stagecoach (1939).

I watched one movie as a teenager that so moved me, I was a different person when it finished: John Ford’s Stagecoach (1939). I have watched it once a year more or less ever since.

Some movies are so seminal to the progress of cinema they get taken for granted and ultimately become a kind of pop culture wallpaper because they are mentioned, referenced, imitated, absorbed so much. In some ways this feels to be Stagecoach’s fate. Stagecoach is not as shockingly anti-heroic as The Searchers nor as civic minded as The Grapes of Wrath. Stagecoach is not as elegiac as How Green Was My Valley nor as revisionist as The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence.

What Stagecoach is, is one of the rare perfect movies.

Not just for John Ford but for all of cinema.

In most Ford movies, one aspect of Ford’s stye can sometimes disproportionately become obvious. It can be his blunt use of broad low comedy (often in the form of alcoholics and drunks). It can be his love of dances, traditions, and songs to create sequences of community. Or it can be his sometimes ambling approach to storytelling proper (depending on the quality of the script) which can often give a Ford movie the appearance of making itself up as it goes along.

In Stagecoach, everything that John Ford is good at-deep humanism, cinematic poetry, breathtaking action, incredible staging in depth of groups, sly criticisms of “respectable society”, identification with the misfit, the outcast, the minority, all achieves a kind of artistic golden mean.

When I watch Stagecoach, I always marvel at how efficiently (yet expressively) Ford introduces and establishes the conflicts and relationship of the 9 people who will take the stagecoach to Lordesbourg through hostile Native American territory. I further marvel at how Ford holds back John Wayne’s introduction as the charismatic Ringo Kid until relatively late in the picture with one of the all-time great character introductions (a quick tracking shot towards Wayne cocking and rotating a long gun to get the coach’s attention). In the middle of the story, Ford suddenly stops all the action to focus on the all-night delivery of a baby which then acts as the mechanism by which the outlaw Ringo Kid and the exiled prostitute Dallas (a wonderful Claire Trevor) finally express their love for each other. And this in turn leads to one of Ford’s most beautifully poetic shots (to me at least) as Wayne lights a cigarette on a gaslamp in the middle ground of a hallway as Trevor pulls her shawl tight around her shoulders and walks out into the night leaving a long shadow to dust the darkened corridor floor.

Stagecoach is graced by multiple amazing character performances-most notably from Thomas Mitchell as the alcoholic Doctor Boone and John Carradine as a dissolute but bound to a code of honor gambler. It contains one of the only times I can remember where a movie pulls off a double climax (the actual fight with the Native Americans while the stagecoach speeds across salt flats followed by the Ringo Kid’s showdown in Lordsbourg with the men who killed his family. And it also somehow manages to include an incredible scene of German expressionist psychology as Wayne walks Trevor to her new home only to realize (via the elaborately constructed sets, actors staged in depth, chiascouro lighting) that she is going to work in a bordello.

Stagecoach even includes one of the great near last lines (“Well they’re free from the blessings of civilization”).

Ultimately the truly great movies achieve both a surmounting of a height and a harmonization of balance. When I watch Stagecoach, I get everything out of the movie that I have ever wanted to get out of any movie. I am entertained. I am moved emotionally. I am put on the edge of my seat. I am wowed. I am brought closer and made less judgmental of my fellow travelers.

John Ford’s Stagecoach is the epitome of what American cinema can be at its best: BOTH entertaining and artistically nutritious.

Orson Welles was no dummy for watching Stagecoach forty times. It’s one of those rare movies that just might make might your world a bit better by the simple watching of it.

Craig Hammill is the founder.programmer of Secret Movie Club.