JOHN FORD: Chapter 1 Fort Apache, The Informer, The Fugitive & the flawed protagonist by Craig Hammill

As part of our The Ford Fundamentals: John Ford Director of 2022 series, founder.programmer Craig Hammill is writing an appreciation in 12 chapters, a prologue, and an epilogue across the year.

Important Note: Movies will be talked about in depth so definitely spoilers!

CHAPTER 1: "As long as the regiment lives..”

Ford, Flawed Heroes, Flawed Institutions, & Faith

This week, we kick off our John Ford Director of 2022 series with Fort Apache (1948), The Informer (1935), and The Fugitive (1947).

In that interesting way the subconscious works, we didn’t realize this when we programmed this week but all three movies center around extremely flawed protagonists. Ford of course made many pictures with extremely flawed protagonists-The Searchers, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, The Last Hurrah-are just a few that immediately leap to mind.

What is singular about this week’s slate of pictures is that each of the characters meet their deaths with a kind of dignity and realization they may not have completely had at the beginning of the picture. Another hallmark of Ford’s genius and storytelling ability.

As we start, it might be helpful to roughly group certain subsets of Ford movies. There are the Westerns, of course. Throughout his entire career, Ford regularly made Westerns as a stablizer or way of re-centering or even simply as a way to make sure he made a hit so he could keep experimenting in other genres. His westerns are so wide and varied and genius that even they deserve further subsets. But for now, to keep it simple, we’ll just name check Stagecoach, My Darling Clementine, Fort Apache, WagonMaster, The Searchers, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance as some of his best known work in that genre.

Then there are the explicitly Irish and Irish Catholic movies. The Informer, How Green Was My Valley (though about Welsh miners very much feels like its about Irish family dynamics), The Quiet Man probably being the most well-known. The Fugitive though it’s based on a Graham Greene novel and takes place in an unnamed Latin American country very much deals with Ford’s faith and Catholicism as it centers on a Catholic Priest.

There are the naval or “out at sea” movies (Ford usually was on his boat and. . .often “taken drunk” as he would say when he wasn’t shooting a picture; he was also a decorated Rear Admiral in the US Navy and agent of the OSS (the proto-CIA) during World War II). The Hurricane, The Long Voyage Home, They Were Expendable, Mister Roberts are just a few that can be name checked.

And then there are the American history/American culture pictures which span the Revolutionary war (Drums Along the Mohawk) up to Ford’s modern day-the 1950’s-with his masterpiece on the passing of political machine politicians for TV-ready handsome politicians in The Last Hurrah. The Prisoner of Shark Island, Young Mr. Lincoln, The Grapes of Wrath, The Iron Horse all fall in this category.

And finally there are the home-spun comedies, a smaller subset, but one very close to Ford’s heart (Ford felt comedy was his forte as he told Peter Bogdonavich). The best of these are probably the three movies he made with folksy comedian Will Rogers in the 1930’s-Dr. Bull, Judge Priest, and Steamboat Around the Bend. But no matter the genre, Ford always punctuated it with scenes of humor (mostly successful and if we’re honest also often clunky and forced).

And then there are the total departures that sometimes yielded wonderfully underappreciated results. One of my personal favorite Ford’s Wee Willie Winkie is a Shirley Temple children’s movie, the first of an unofficial trilogy of “wisdom when to fight and when not to fight” movies that continues with Fort Apache and reaches its apotheosis with The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance.

Whew! And we haven’t even scratched the surface of Ford. But we’ve got a whole year so let’s move on. . .

So let’s dig into the three we show this week. Fort Apache, a Western, The Informer, explicitly about the Irish and the IRA, and The Fugitive, about spirituality, faith, and religion.

Fort Apache, a fictional re-telling of Custer’s last stand, is a fascinatingly complex movie parading as another John Ford western. One of the main characters-Colonel Thursday (played by Henry Fonda in a complex brutal stubborn performance)-is an obstinate by the books US Cavalry leader. He refuses to heed his second in command’s experience (John Wayne as Captain Yorke, an ally and friend to the local Apache tribes) and leads his men into a suicide run by antagonizing then attempting to defeat an Apache tribe that only wants the white men to honor their commitments and let them live in peace.

What makes Fort Apache such a key work in Ford’s canon is how Ford weaves in so many of the strands of his genius into one work. There’s the re-examination of American history while still affirming the need for legend and myth. There’s the celebration of communal ritual both of the Cavalry (the dances, the dinners, the protocol) and of family (the Thursdays, the O’ Roarkes). Two of my favorite shots in the entire picture are single compositions/shots YET cinematically devastating. When a dance is broken up for the ill-fated charge on the Apache, Shirley Temple (now an adult in her 2nd Ford picture) and John Agar (her actual husband, here playing her suitor) sneak out to the porch and quietly dance together in the night, a dance they’ve been waiting to have and refuse to let the military commands deny them again.

Note here John Ford’s unparalleled (to this day) ability to stage groups of actors so scenes can be accomplished in masters that most directors would break up into two shots, singles, over the shoulders, etc.

And at the end when the Apache leader Cochise is within his rights to continue his fight to Captain Yorke and massacre all the cavalry, Cochise surprisingly and powerfully refrains. Instead, he rides up to Yorke, plants an American flag in the ground angrily as a symbol of America’s broken commitments to the Apache, then rides off, leaving Yorke and all the other embarrassed men in a cloud of dust that consumes them.

Ford’s complexity really reaches its peak in the very last scene of the movie when Captain Yorke, now the leader of Fort Apache, decides to lie and tell the newspapermen that Colonel Thursday was the hero they think he was (rather than the stubborn racist who unnecessarily lead his men to slaughter). Yorke also asserts that even the lesser known men who died will be remembered as long as the regiment itself lives.

This is Ford at his most honest and his most complex. Ford, especially after his service in World War II, came believe in the importance of institutions despite their clear and constant flaws. Even if individuals within those systems were often stupid, ignorant, corrupt. Ford understood the importance of legend and myth as a necessary narrative to inspire and bind a peoples as diverse as the ocean of immigrants that made up the United States. Stories are somehow the short hand to communal bonding. And they need to be told.

Ford’s view, or this institutionalist view, has its obvious problems and limitations. Certain institutions need to be overthrown or at the very least questioned, improved. Problems and limitations FORD HIMSELF would acknowledge and explore.

For fun, if you’re an Akira Kurosawa fan, watch also the comedic scenes of Toshiro Mifune training villagers to be warriors in Seven Samurai and notice how Kurosawa uses almost the exact same shot composition (and even the same jokes) as those used in similar scenes inFort Apache. (Kurosawa always stated he primarily studied John Ford for cinematic composition).

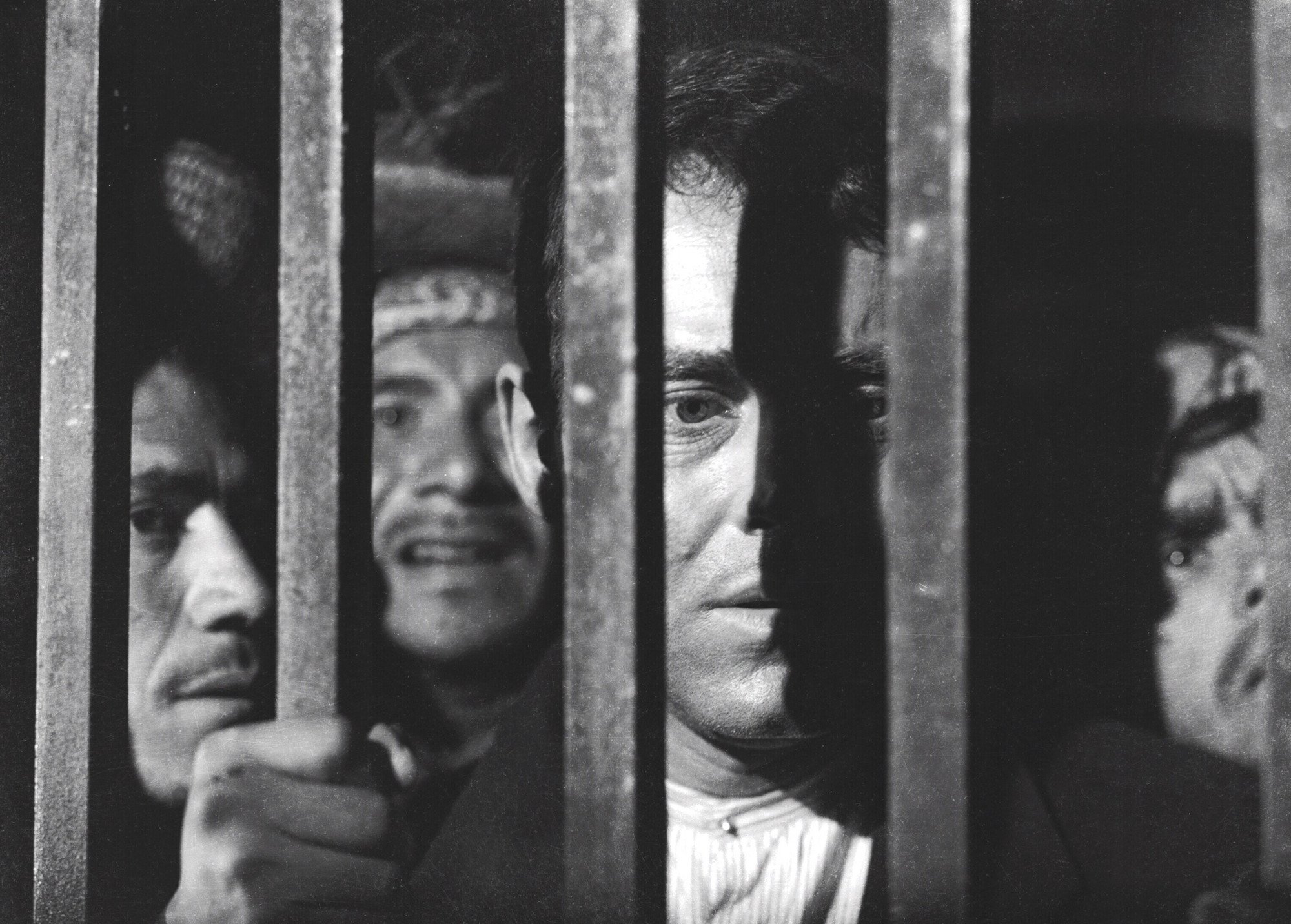

From Fort Apache, let’s briefly move to Ford’s real break-out hit, the 1935 The Informer starring Ford regular Victor Maclaglen as Gypo Nolan, a disgraced IRA rebel who sells out his friend for the reward money so he can runaway with his love. Though Ford was already an established top director in Hollywood before The Informer (Ford’s silent film The Iron Horse had been a wild success), the Ford “style” really goes to the next level here.

Ford had to fight and fight to get the movie made and finished. Nobody wanted it. And the top brass even tried to shut it down mid production because they thought it was going to be a huge flop.

Ford had been so blown away by FW Murnau’s Sunrise (and possibly Fritz Lang’s M which The Informer greatly resembles) that he soon absorbed and used German expressionistic techniques (specifically the deep focus framing/staging, the atmospheric sets, the use of foreground, middle ground, background varied levels of action) in his work. The Informer is probably Ford at his most expressionistic. Though certainly many aspects of the movie and its direction now feel a little too “overly arty” and the expressions of Catholic guilt over the top, The Informer is still a textbook to study of a talented director taking wild chances with shots, image, sound to create something wholey, uniquely cinematic that expresses a character’s psychological state through sound + image + editing rather than dialogue.

You can see Scorsese quote The Informer in The Departed (the famous church scene plays on a television). And it’s important to note that this was the movie for which Ford won his first Academy Award as Best Director along with a slew of critics’ awards. In many ways, The Informer bought Ford the space to get the studio heads to trust him with varied projects. The Big Bosses had all thought the movie was going to tank. When it not only made money BUT ALSO won big awards, the Bosses had to admit maybe John Ford knew something they didn’t. And Ford probably cherished, nurtured, and encouraged this view for the rest of his career so people would leave him alone.

Ford’s The Fugitive starring Henry Fonda as a nameless priest in a country that has outlawed religion and Pedro Armandariz as the fascist police captain who hunts Fonda down is probably the least known of the three pictures we show this week. And it certainly has problems. Ford had to change Graham Greene’s novel The Power and the Glory to get the movie by the censors. In the novel, the Priest has a girlfriend and a child. So not only is he in opposition to the fascist government but he has broken the rules of the Catholic church. Ford gives the illegitimate child and mother to the Fascist Captain instead. And this definitely dilutes the impact of the narrative since Fonda comes across as a bit too saintly and non-descript from the beginning.

But The Fugitive still has a tremendous power (and shades of the novel Silence by Japanese Catholic Shushako Endo which would be made into a movie by Martin Scorsese in 2016. By all accounts, Ford is one of the very rare directors who appears to have retained his spiritual faith his entire life. A very powerful spirituality, Ford expressed again and again in his movies.

Certainly Ford’s own personal behavior-his many affairs, his abusive treatment of his repertory company, his alcoholism-must have complicated his faith and expressionism of his faith. But movies like The Fugitive show Ford’s profoundly wise understanding that faith and spirituality (as distinct from the political and power-dynamics side of religion) are critical and cherished by people. And that even (or especially) when governments forbid its practice or try to stamp it out of people, people will EXPRESS it and PRACTICE IT with even more commitment.

The spirituality of Ford, even spirituality in general, is the most difficult thing to write about. Because everyone comes to their beliefs (or non-beliefs or unique beliefs) their own way. And everyone’s journey is hard-earned. And almost everyone’s belief systems deserve the same respect one would want for one’s own belief systems. Ford also seemed acutely aware of this as evidenced by the many personal anecdotes of how Ford would learn the languages and customs of others when meeting them.

Ford often felt that his own Irish Catholicism and the spirituality of the Native American tribes were much more similar than people realized.

And The Fugitive ends with a very powerful scene of forgiveness and an expression/admission of faith from a character who had up to the end professed to be an atheist. These are powerful and dangerous themes Ford is expressing. And it’s amazing he was able to get this (he often said The Fugitive was one of the small movies he made for himself after he’d made a hit for the powers that be) green lit and made.

The Fugitive, shot by ace Mexican cinematographer Gabriel Figueroa, also has one of the greatest sequences of ANY FORD movie which alone is worth the price of admission. It occurs roughly in the middle of the picture and is a sudden blast of expressionistic editing, shot selection, and sequence construction. These moments are replete in Ford and the very essence of why it’s so important to study him: to learn cinematic poetry.

Okay. . .damn. Let’s stop here. Watch these movies. See what you think. And let’s continue on this journey.

Chapter 2 coming in February!

Craig Hammill is the founder.programmer of Secret Movie Club.