Great Horror Movie Subgenres by Craig Hammill (SMC Founder)

This programmer would be grateful to really dig into one of his favorite genres: horror. What amazes me is how adaptable horror is as a genre. It has so many subgenres that it's a dark rainbow of possibilities. Horror is also an amazing vessel for so many kinds of inquiries.

APOCALYPTIC HORROR

Pulse (2001, dir by Kyoshi Kurosawa, Japan)

First up, I wanted to talk about the APOCALYPTIC HORROR subgenre. Basically this is the horror movie that starts in our current time (or some recognizable historic time) but slowly morphs into the end of the world. One of the greatest examples of this horror subgenre is Kyoshi Kurosawa's original Japanese Pulse (not the American remake). Basically a movie that starts about a group of college friends who discover one of their friends has found a way to communicate with ghosts on the internet. But as simple (or silly) as that premise may sound, Kurosawa is driving at something even more terrifying than ghosts: loneliness and isolation. As each friend discovers that there's a forbidden website with instructions on how to make a forbidden room to summon the ghosts, they start to become isolated from each other. And from there, folks outside their circle start to discover the website. Because, it is the internet after all. There are many great Apocalyptic horror movies. Hitchcock's The Birds and the Coen Brothers' No Country for Old Men (even though many see No Country as a Western, I've always seen this one as much more terrifying and dark) both start in a recognizable world but then get overwhelmed by an inexplicable force, antagonistic to humanity (sometimes for good reason, sometimes not). These horror movies may cathartically help us deal with our end of days fantasies so we can keep on persisting. But these horror movies at their very best dare to suggest how the world (at least as we humans know it) may end. Pulse, whose last 20-30 minutes include some of the most unsettling images ever put to a horror movie, taps into this kind of horror like an oil prospector who has just hit the motherlode.

SERIAL KILLER

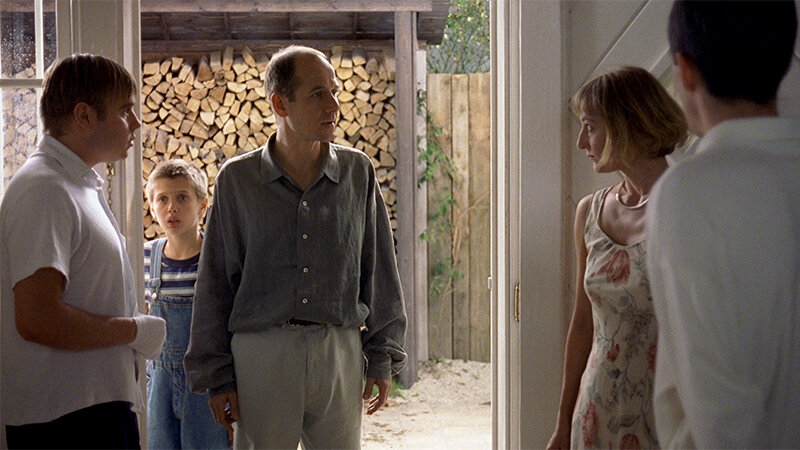

Funny Games (1997, dir by Michael Haneke, Austria)

[NOTE: Make sure to watch the Austrian original in German; not the American remake.]

An upper middle class husband, wife, and son head to their summer house on the lake for some relaxing times. Two young men dressed in what appear to be all white tennis clothes show up at their door. From there the movie descends into the unimaginable. Like so much about horror, this movie could be classified in any number of subgenres: apocalyptic, family as horror. But we're classifying it as a serial killer horror movie. What amazing director Michael Haneke is actually driving at only becomes (terrifyingly apparent) as the movie goes on. We're not going to spoil it for you but this movie has one of the most famous twists of modern horror. And it's such a shock that you simultaneously laugh out loud and scream "NO!!!!!!!" at the same time. At its rotted heart, the serial killer genre may be our fear of running into a fellow human being who just doesn't play by the rules of society. Our fear of suddenly being held prisoner (or worse) by someone we can't reason with, draw empathy out of, bargain with. My Uncle was an LA police detective and he told me the scariest moment of his life was interviewing a murderer in prison and having to look into his shark eyes and realizing there was just nothing there. There IS something in the eyes of the two young men in this movie but it's a kind of non-comprehension that their violent sense of "fun" may be wrong. Great serial killer movies like Psycho, Cure, Silence of the Lambs, Black Christmas, and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre all, on some level, are about the inscrutability of the killer(s) themselves. What Haneke is driving at in this movie is something even more horrifying than that. An entire society of sociopaths.

COMEDY-HORROR

Dead Alive (1992, dir by Peter Jackson, New Zealand)

Still (in this programmer's humble opinion) one of Peter Jackson's absolute best movies, Jackson flips the zombie movie on its head with a clever twist. A loving son whose mother has become a zombie (from a zombie monkey bite!) tries to keep her and all the people she makes zombies in the house rather than fight zombies to keep them out. This funny twist on the usual formula then generates endlessly hilarious almost Charlie Chaplin/Buster Keatonesque comedy sequences. But don't get it twisted. This is one of the most graphic, over the top, GROSS movies you will ever see. You can practically hear Jackson shrieking with glee at all the super gross practical effects he pulls off: a zombie baby gets born, a woman's head gets ripped in two by said zombie baby, our hero has to take a lawnmower to the zombies. Throughout the whole movie, Jackson miraculously keeps the tone both light (a priest at one point takes on zombies by exclaiming "I kick a*@ for the Lord!") and surprisingly touching. And like so many great horror movies there's a subtext going on here about how needy/possessive family members can unfairly hold back loved ones with their neediness. But forget all that. Just remember this: this programmer first saw this movie at 18 when he had a really bad cough. I remember laughing and almost throwing up at the same time because I found the movie both hilarious and disgusting. I've never had that reaction in any other movie before or since. A MUST SEE!!!

ZOMBIE HORROR

Night of the Living Dead (1968, dir by George Romero, USA)

Hilariously enough, even though Peter Jackson's Dead Alive is a zombie movie, the comedy-horror is what shines through. In George Romero's horror Rosetta Stone, Night of the Living Dead, you actually watch the zombie genre (still being mined to this very moment) being born. A strange outbreak of some kind causes the dead to rise out of the grave. Though they move slowly, if they get you, they eat your brains, then your vital organs, and turn you into a zombie. A group of strangers hole up in a country house to try to hold the zombies off outside and end up fighting as much with each other. Everything about what makes classic horror is right here. A limited location (one house), a dynamite hook (the zombies), a great satirical subtext (the strangers are as roiled by racism and distrust inside the house as fear of the zombies outside). What makes Zombie movies so evergreen is, I'm sure, a matter of subjective opinion among different folks. For this programmer, the zombie genre stands in as a kind of terrifying metaphor for infection/plague of any kind. What Romero does so brilliantly here (and even more brilliantly in Dawn of the Dead although there he really veers into horror-satire) is to really point out that "infection" isn't just physiological. When humanity gets infected by "racism", "materialism", the "mob mentality", when we stop using our brains and our hearts (hence maybe why the zombies like to eat those organs) and instead give in to hysteria and fear, humanity really is at horrible risk.

FOLK TALE HORROR

Let the Right One In (2008, dir by Tomas Alfredson, Swedish)

This programmer defines folk tale horror as any horror movie based on a character born out of a mix of fact/history/rumor/folk tales in human history. Case in point: The Vampire. The Vampire and vampire lore is a great example of the amazing crowd-sourcing/open code nature of our most enduring "monsters". Each great work can add a rule or parameter that all artists afterwards absorb and accept as law because it captures the imagination. It wasn't Bram Stoker's Dracula that invented the rule the vampires hate sunlight and come out at night (in that book, light just bugged them but they could totally walk around in the day), it was FW Murnau's movie Nosferatu that invented that rule. The amazing 2008 Swedish horror film Let the Right One In takes all the rules then advances the mythology with some interesting additions of its own (which very well may be absorbed and used in future vampire movies). Introverted tween Oskar, often bullied at school, meets new apartment neighbor Eli, a beautiful but strangely nocturnal and home-schooled girl. They start to form a bond. The title of the movie itself references the rule that you have to invite a vampire into your house. A vampire can not just enter. Alfredson's gorgeously strange and cinematic operetta of a movie is a both a strangely emotional coming of age love story AND, like a spy in the night, the story of one very important aspect of vampire mythology that we don't fully realize until near the end of the movie. One of the benefits of how our folk tales develop rules is how quickly we can then create suspense, tension, irony in the story. The listener knows the rules of the game from hundreds of years of creepy nighttime stories. Folk Tale horror is an endless well of our collective unconscious' continuous anxiety about certain aspects of existence we'll never fully square or be comfortable with. . .so we cathartically seem to rehash it again and again in these stories.

SEXUAL HORROR

Dead Ringers (1988, dir by David Cronenberg, Canada)

This subgenre is a tough one because it often overlaps with body horror and psychological horror/thriller. But like the old judge used to say. . .you know it when you see it. Cronenberg's Dead Ringers tells the story of twin gynecologists (both played by Jeremy Irons), Elliot, the confident one, and Beverly, the brilliant but insecure one, who often share girlfriends without the girlfriends knowing. When Claire, a painkiller addicted actress, comes into their lives, everything blows up, including the fragile equilibrium of the twins' own mental states. Let me just get this out there by saying, this movie is mega-disturbing. You can't UNWATCH it. Cronenberg explores a whole host of sexual and identity issues here. Why are some of us confident sexually while others of us never gain that footing in our lives? Why does the expression of sexuality often disrupt and upend relationships we have outside of our sexual relationships? Why is expression of sexuality so wound up in deep-rooted personal trauma? Cronenberg, more bravely and with more clarity than almost any modern director, has taken on sexual horror a number of times in movies like Rabid, The Brood, Videodrome, and Crash. Like so much great horror, the genre allows us to cathartically explore questions we often are uncomfortable dealing with in a more direct, realistic way. Dead Ringers is this programmer's personal favorite Cronenberg. The movie is horrifying and deeply unsettling. Yet it's done in such a classically stylish way that it's like listening to a Mozart symphony written specifically to scare the hell out of you. By the time the gynecologists are losing their minds and creating tools for "mutant women", you know you're going right down the whirlpool to the psychological depths.

SCI-FI HORROR

The Thing (1982, dir by John Carpenter, USA)

Horror is one of those unique genres that goes really well with other genres. Horror-comedy works really well in the hands of folks like Sam Raimi, Peter Jackson, even Steven Spielberg. Sci-Fi Horror is a smuggler's dream because you can market a movie as being sci-fi when it's obvious after the first few scenes that it's going to scare the heck out of you. In The Thing, the Alien is on earth and its very nature (it is able to reproduce itself immediately and imitate the thing it takes over) could threaten the entire fabric of all terrestrial existence. John Carpenter weaves together his favorite plots and obsessions into one thrilling, horrifying, jaw dropping horror experience. We get the Rio Bravo-esque setup of people alone in a remote outpost fighting an overwhelming enemy (in fact Kurt Russell appears to be doing a great John Wayne through a lot of the movie). We also get possibly the best of all time practical special makeup and creature effects courtesy of Rob Bottin. The Thing also qualifies as Apocalyptic Horror because of the implications of the alien itself (it could potentially take over and imitate all life on earth within mere weeks). What the sci-fi aspect of the concept does so well here is actually offer the glimmer of hope that maybe these scientists on this Antarctic outpost can contain and kill the Thing. Also sci-fi can often be more immediately terrifying because while we are all pretty sure vampires and werewolves are folk tales, it is very likely that aliens are out there. And we have no idea what they will be like. The brilliant tension of The Thing (as with so many great horror movies) is whether the scientists' natural lizard brain reactions of panic, irrationality, and emotion will prevent them from forming a workable plan in time before every one of them gets taken over.

THE DEVIL

Toby Dammit (1968, dir by Federico Fellini, Italy/France/England/USA)

Made as the third and final part of Spirits of the Dead, an omnibus film of Edgar Allan Poe short stories, Fellini's Toby Dammit is one of this programmer's personal favorite Fellini movies. It tells the story of a drug addled, sex-addicted, alcoholic actor who comes to Italy to make a Catholic western (?!). In the airport in Rome, he first sees a little girl who wants him to play with her (no one else sees her). Later, in a fit of self-destructive rage, he takes the sports car that's been bought for him, and tears through Italian towns and the countryside until he meets the girl again. . .Based on Poe's Never Bet the Devil Your Head, Fellini takes stylistic chances here that are truly unsettling. This programmer will never forget how unsettling the extended car sequence is: no dialogue, beautiful strange POV shots down streets, and mannequins often in the place of actual actors. Like La Dolce Vita, there's a recognition here of the ultimate spiritual bankruptcy of decadence and hedonism. Or put another way, Fellini was always keenly aware that the temptations he often fell prey to were dead ends, no matter how attractive they initially seemed. One of the greatest moments of genius in all horror is Fellini's decision to represent the devil as a little girl. Most of us lazier moviemakers go for the demon or urbane gentleman thing. But when you meet the Devil in horror, the Devil has to be a formidable foe with great power to confuse, seduce, trick you. What could be more misleading than pretending to the purity and innocence of a child..

THE HAUNTED HOUSE

The Shining (1980, dir by Stanley Kubrick, USA)

Based on Stephen King's (brilliant) novel of the same name, The Shining tells the story of alcoholic writer Jack Torrance, his wife Wendy, and their psychic son Danny, who take care of the Overlook Hotel during the winter only to discover, when they are totally snowbound, that the hotel is deeply, deeply haunted. The Haunted House subgenre is full of wildly fun titles: The Haunting of Hill House, House (the Japanese movie), you name it. In these movies, a group of people often find themselves in an old, creepy, atmospheric building that begins to act like a supernatural maze from which they can't escape. What Kubrick does is to add a brilliant psychological layer to this formula: what happens when you isolate certain families and give them no escape from each other-they become murderous and homicidal. Kubrick studied the horror genre obsessively so he could make the absolute best horror movie. One of his greatest insights was how important "the uncanny" is to horror. The uncanny can be defined as the psychological experience of something strangely familiar encountered in an unsettling, eerie, or taboo context. When Danny encounters two twin girls in a hotel hallway who should not be there, we know we're in for a ride. The image later on in the movie of the strange man in a dog suit in a hotel room (also in King's novel by the way) is one of the weirdest most unsettling horror images of the past 40 years. Stephen King famously hates the movie because it took King's emotional warmth and turned the thermostat to freezing. But what may be more telling is Kubrick's first comment to King in their first phone conversation. Kubrick asked King if he agreed that any supernatural tale is a tale of optimism because it posits that there is something after death. Given this was where Kubrick was starting, you can only imagine the dark narrow streets he ends up pursuing when he commits to the concept...

THE GHOST STORY

The Innocents (1961, dir by Jack Clayton, UK)

Based on Henry James' The Turn of the Screw, The Innocents tells the story of a tightly wound governess (played brilliantly by the always great Deborah Kerr) who begins to see ghosts and believe that the children she is watching have been "possessed" by the spirits of two illicit lovers who used to work on the property. This programmer will never forget the brilliant shock he received when he first watched this movie and there was a ghost moment in BROAD DAYLIGHT! Ghost story cliches so often find storytellers telling stories at night. Deborah Kerr's visions of ghosts in the day are a revelation. The Ghost Story can fall into two camps. Either the ghosts are clearly real from the beginning. Or we're left to wonder if the ghosts are real or a figment of a troubled mind's own psychology. The Innocents, for most of its running time, falls into the latter category. We become increasingly aware that Deborah Kerr herself is a flawed, sexually repressed, troubled narrator and we begin to worry her growing belief that the kids are possessed is going to lead to harm to the kids. This dual tension makes everything even more unbearable. The Ghost Story truly is the universal horror genre in that every culture has its own narratives on ghosts and the spirits of the dead. And in a weird way, while many may suggest this is just wishful thinking, one has to ask oneself this question. Antiquated concepts fall away. Few folks are still arguing that the earth is flat. But for 200,000+ years and counting, human beings are still reporting ghost experiences.

PRIMAL FEARS

Jaws (1975, dir by Steven Spielberg, USA)

For the purposes of this subgenre, we define "primal fears" horror as those horror movies that deal with things that could still actually happen where we suddenly become the prey and not the predator. Very few things are as primal as the fear of a shark attack. Or really any attack by any animal in an environment where we would clearly not have the upper hand. Steven Spielberg's Jaws (rated PG at the time by the way!) is possibly the most perfect primal fear horror movie ever made. A shark begins to attack the beaches of a tourist town. The newly installed Sheriff Brody must partner with a Scientist and a shark-hating Fisherman to go out to sea and try to hunt the shark down before it kills again. Jaws has one of the great first half/second half divides of any movie. For the first half of the picture, we're on land watching the havoc the shark attacks wreck on the psychology of the small town (and the Sheriff tasked to protect it). But the second half takes place completely out at sea and becomes just a four person picture: the three human hunters and the shark. Spielberg and his editor, Verna Fields, somehow found the perfect way to balance comedy, rousing action-adventure, and out and out horror, in a way nobody has topped since. One of the greatest realizations of this picture is that you should save the graphic on-screen explicit shark attack for a special moment. Until then, the shark is a mostly unseen menace whose presence is felt by the visible results of its actions. When we finally get our first full glimpse of the shark, well into the near 2 hour running time of the picture, it turns out to be JUST AS HORRIFYING AS WE THOUGHT IT WOULD BE. This movie was so effective in re-awakening our lizard brain realizations that the sea is teeming with creatures we barely understand that folks were reportedly afraid to go swimming for a few years. Just a perfectly directed, edited, paced, structured movie on all levels.

THE OCCULT

Night of the Demon (1957, dir by Jacques Tourneur, UK)

A skeptical American Professor arrives in London for a parapsychology conference only to discover a colleague dead. From there, he descends into a strange world of Satanists, mediums, and chants to uncover what happened. Directed by the great Jacques Tourneur (Cat People, Out of the Past, I Walked With a Zombie), Demon's greatness resides largely on the amazing atmosphere and dread that Tourneur builds as our hero goes on his nocturnal journey. Occult horror is a bit different from The Devil subgenre in that often it focuses more on the strange societies that dabble in dark arts most of us wouldn't get near with a ten foot pole. Movies like The Wicker Man, Rosemary's Baby, and Night of the Demon offer the audience member a vicarious "Get out of jail free card" to examine these societies/organizations without ever having to join or even visit one in person. And usually the movies that succeed have a central character who begins the movie "not believing" any of the mumbo jumbo. Only to realize, horrifyingly, that something "supernatural" does exist and can be summoned (but shouldn't)! The world is still populated with psychics, cults, seances, mediums who claim to speak to the dead, etc. Night of the Demon very cleverly (and terrifyingly) takes our hand and leads us into a descent into this underworld. But as with all great cinema, it also promises to let us back up to the light when the end credits roll.

SUBVERSIVE HORROR

The Invisible Man (1933, dir by James Whale, USA)

A completely bandaged man shows up at an inn demanding a room. His erratic behavior terrifies the innkeeper and village people. From there, we learn that Dr. Jack Griffin has created a serum that made him completely invisible and is slowly driving him mad. The subversive horror movie smuggles in a clearly topical, often bitingly critical view of contemporary society but slyly buries it in the horror. It's there if you want to see it, it's not if you just want to be entertained. While there are many more immediately acknowledged subversive horror movies like Whales' own Bride of Frankenstein and Romero's crown jewel Dawn of the Dead, Whales' The Invisible Man (the 1933 original) is one of those great horror movies we recommend as highly as possible you re-discover. It is incredibly well-directed, tightening the screws of tension from its very first scene. Claude Rains (in his 1st US screen appearance, ironically almost never seen) enthralls us with just his Shakespearean voice and bold physicality since he has to perform most of the role either as a voice or under bandages. What you slowly realize as you watch the movie, and especially if you know that director James Whale was one of the few openly gay directors in the 1930's, is that the whole movie takes on an interesting subtext of being invisible in plain sight. The Invisible Man is clearly a genius, talented and yet he is also clearly an outsider, hated by normal society. The strange conflict the Invisible Man has with himself throughout the movie-he invented and took the serum and it is driving him slowly crazy-can almost be read as the struggle any outsider has when who they are is rejected by the wider mass society. A kind of internal self-conflict arises. Horror movies have always been one of the greatest genres to smuggle in investigations of the hypocrisies of greater society. Folks don't get as offended and so moviemakers can go full throttle on investigating things a more straight-forward approach might risk unhelpful controversy. So for all the smugglers out there, consider the horror genre...

BODY HORROR

The Fly (1986, dir by David Cronenberg, Canada/USA)

Scientist Seth Brundle invites journalist Veronica Quaife to an exclusive story about his molecular transporter and they become romantically involved. But when Brundle tries the device one night, he and a fly unknowingly transport together and their DNA starts to merge in a horrifyingly unexpected way. Body Horror often focuses on a character who undergoes some kind of unbearable body transformation becoming a metaphor for cancer and other body changing diseases. It can also become a metaphor for radiation poisoning and nuclear energy. No one has mined this terrain more or better than David Cronenberg. His early and middle work almost obsessively focuses on uncontrollable body transformation of his main characters. This is tough material to watch let alone be entertained by. Which is why Cronenberg's remake of The Fly is such a miracle. It is both an utterly entertaining and thrilling horror movie AND an intense Cronenbergian exploration of a body revolting on its owner. Here and in other Body Horror movies like Pedro Almodovar's The Skin I Live In, Georges Franju's Eyes Without a Face, and even Cronenberg's later Crash, characters must deal with the exquisitely painful tension of inheriting new bodies they didn't ask for that sometimes come with unexpected perks (here Jeff Goldblum's scientist suddenly finds he has unlimited energy and strength) but also an almost unbearable price tag (but slowly that same new body decays, deteriorates, and forces Golblum to take on fly characteristics that repulse him and others). Often explicit to the extreme, body horror, at its best, forces us to wrestle with the reality of what we'll do when our own bodies start to break down and turn on us. It's not a subject anyone wants to think about. But it is one, many of us will have to face.

SCUZZY/LOW BUDGET HORROR

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974, dir by Tobe Hooper, USA)

A group of teens explore an abandoned property only to realize too late a monstrous family of cannibals occupy the house in the back. Scuzzy low budget horror is that weird subgenre where the subject matter seems off-putting and the budget was clearly very low and yet the filmmakers made a genius movie. Hooper's Texas Chainsaw, Wes Craven's The Hills Have Eyes, Raimi's The Evil Dead, etc. But in each instance, the very talented moviemakers somehow transcended (or committed fully to) the material to make the movie work far better than anyone had any right to think it could. As unsettling or gory as these movies can sometimes be, they all share in common a consensus among movie lovers of their superior quality. Hooper's original Texas Chainsaw may be the most brilliant example of this genre. I avoided watching this movie until my mid 30's because I just felt it was going to be unpleasant and gory. I've never liked slasher movies and this just seemed an even more intense version of that. I'm not sure why I thought that. But finally I read too many good things about it and committed to seeing it. But watching the actual movie was a revelation. One of the most truly TERRIFYING horror movies ever made, Hooper actually directs everything with an almost Hitchcockian understanding of withholding the real horror for a long time. When Leatherface, the almost childlike butcher/killer for his family appears, he is at once both unfathomable and scarily childlike. What no one tells you is that the movie takes a hilarious left turn two thirds of the way in and becomes a deeply dark comedy about family for its final 30 minutes. When one of our characters is forced to have "dinner" with the family, one of the most unbearably strange and darkly funny scenes of dysfunction and non-comprehension unfurls. Hooper somehow managed here to make a movie that is chilling because of how low budget, scuzzy, and real everything feels. Yet, at the same time, Hooper constructs the movie with such visual and editorial talent that it's clear it's a masterpiece from it's opening.

Written by Craig Hammill. Founder and Programmer of Secret Movie Club.