FIRST FEATURE FIREWORKS

FIRST FEATURE FIREWORKS #12: Who's That Knocking At My Door (1967, dir Martin Scorsese) To kick off the new year, let's take a look at 12 first features this programmer thinks light up cinema with fireworks. First up is Martin Scorsese's debut feature. Like many first features, KNOCKING took Scorsese years, numerous painful re-shoots and re-edits, before it finally found a showable form and hit cinemas. The story of conflicted New York Italian-American Catholic J.R. and his relationship with a woman only ever identified as Girl (a tellingly strange detail), KNOCKING follows their relationship as well as J.R.'s dips into drinking, partying, petty gangsterism. What's fascinating already is Scorsese's awareness that his deep-seated Catholicism both propels and hinders his ability to deal with the world as it is. It allows him to set higher goals than just being a neighborhood tough but it also shackles him to a dogma that interferes with his human relationships. J.R.'s hypocritical feelings about sex and marriage threaten his relationship with the Girl who is clearly shown to be more pragmatic and tolerant than JR. While definitely a rough and uneven work, KNOCKING has so much exciting style here married to committed honesty that you see the template for all of Scorsese's greatest movies. KNOCKING is THE HOBBIT to Scorsese's later "Fellowship" of MEAN STREETS, GOODFELLAS, CASINO, and THE IRISHMAN. In fact, if you watch these 5 movies back to back you see the J.R. character basically age from youth to middle age to old age. What is most exciting here is to see Scorsese swing for the fences with his cinematic instincts. Almost all of the greatest debut features find moviemakers who consciously or not try everything and get it onto the screen. WHO'S THAT KNOCKING AT MY DOOR is both an invitation and warning to hopeful moviemakers: it takes everything to make something great.

FIRST FEATURE FIREWORKS #11: Duel (1971, dir by Steven Spielberg) With each passing year, Spielberg's debut DUEL only seems to get better and better. To the point that, while a different beast, it starts to feel like it belongs on the same tier as CITIZEN KANE. This programmer realizes that statement might seem outrageous but look at the conditions under which DUEL was made. Given only 13 days to shoot this TV Movie of the Week, Spielberg brilliantly planned and shot this cat and mouse chase movie of a feckless middle class "everyman" engaged in a death match of chicken on back roads with a faceless "working class" truck driver. 13 days! To shoot an out and out horror action movie of tremendously difficult logistics. But like so much of Spielberg's best, he is brilliant at hiding how much work this took so that the audience can just enjoy and be thrilled by the final results. Everything that would make Spielberg, Spielberg is all ready here. He has a preternatural understanding of editing, camera mechanics, storytelling. He showcases an ability to accomplish the most bravura of sequences without ever making you OVERLY aware of the filmmaking. He displays a sensitivity to the anxieties of America writ-large. DUEL belongs in that tier of Spielberg's work where he allows his ridiculous talent for suspense, tension, horror the free reign it needs to achieve genius. Movies like DUEL, JAWS, RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK, and later WAR OF THE WORLDS and MUNICH prove that Spielberg may be the best horror director America has ever produced. The irony being that Spielberg also believes in the best of people and the universe. And the tension between these two sides of Spielberg, when resonating at just the right thong of the tuning fork, produce timeless classics of pure cinema like DUEL.

FIRST FILM FIREWORKS #10: CITIZEN KANE (1941, dir by Orson Welles) Let us wrestle with the beast early in the series. There's no point putting it off. Orson Welles' first film, CITIZEN KANE, was made when he was a 25 year old Broadway director tyro with no Hollywood background. RKO gave him complete creative control and promised no interference. Welles got one of the industry's best cinematographers, Gregg Toland, who promptly partnered with Welles to pull off what no one with experience would dare try. Welles and his Mercury Theater team assembled a crackerjack cast, crew. Welles even screened John Ford's STAGECOACH dozens of times in pre-production with various crew heads so he could understood how a great movie was made. CITIZEN KANE is a kind of investigative mystery in which a determined journalist tries to figure out what reclusive 20th century media magnet Charles Foster Kane's last word "Rosebud" meant to his life. Part fictional biography of Kane, part observation of the damage Kane did to all those around him, part takedown of how men with money and power wreck havoc because of their needy egos. KANE is one of those works of art we take for granted now because the last 80 years of cinema, specifically cinema powered by adventurous singular visions, has been a direct result of it. But we shouldn't ever get numb to that. Orson Welles is doing so much successful experimenting in this movie, it's a textbook in how to approach cinema if you want to push the art form forward. He opens with a German Expressionistic prologue of Kane's death scored by Bernard Hermann then immediately jumps to a fake newsreel style encapsulating Kane's life (a super clever way to get through the exposition) then lights the whole box of cinematic fireworks with a movie filled with match cuts, mind-blowing "oners" (large parts of scenes handled in intricately choreographed single shots), incredible foreground, middle ground, background staging, optical effects, lighting changes within a shot, powerhouse performances. Not least in all of this is a 25 year old actor (Welles again) completely believably playing a man from his early 20's through his death in his 80's. Welles does with no CGI help, just makeup, lighting, and performance. What feels so critical about CITIZEN KANE is the light Welles threw to show a cinematic path to everyone after him that to keep a creative medium vital one must learn the rules then experiment and innovate. With movies that means finding ways to use the tools of cinema to tell gripping stories in cinematically thrilling, surprising, and captivating ways. Every generation produces a handful of such adventurers. Here's to those making the next CITIZEN KANE on their smart phones right now.

FIRST FILM FIREWORKS #9: BAD TASTE (1987, dir by Peter Jackson) The future director of unviersally lauded hits HEAVENLY CREATURES and the LORD OF THE RINGS trilogy was a one man New Zealand band on his first feature. Jackson shot on weekends across four years, starred in three key roles, co-wrote, edited, created ALL the practical effects for the movie. BAD TASTE follows a team of four friends and commandos (Jackson's actual friends) who are busy taking down an alien invasion hell bent on turning human beings into intergalactic fast food. Yes. This may be (along with Sam Raimi's THE EVIL DEAD) the greatest z budget movie the kids you know down the street made. BAD TASTE is great fun from the very first scene which finds Jackson and his friends hunting down aliens (who disguise themselves as humans dressed all in denim) in a coastal town. From there, Jackson is hell bent on upping the "how did they do that?!" factor in each scene. First he (as director/cinematographer) shoots a scene where he (as comic relief gung-ho commando Derek) literally fights himself (as a bearded alien) on a cliff ledge (the two parts were shot months apart from each other). Then he introduces buckets and buckets of splatter gore. Finally, we end up at the alien base (a two story Victorian home) with one of the hands down grossest yet most hilarious "vomit" sequences ever put to film. Oh yeah, we also see a sheep get blown up with a rocket launcher. In many ways, Jackson tips his hat with the title. This movie is not here to be a profound meditation on the ambiguities of the human soul. This movie is here to make you laugh your a@! off by having Peter Jackson saw through an alien by jumping into its mouth and coming out its backside covered in goo. Most important, BAD TASTE shows a filmmaker willing to take the time (four years) to use his ingenuity to deliver a $25,000.00 (initially) sci-fi comedy all practical effects splatterfest that delivers beyond all expectation on imagination, gore, comedy, and entertainment using the barest of resources. The experience of watching this movie is like seeing someone build a spaceship out of aluminum foil, scuba diving equipment, and twine and actually fly it to the moon. BAD TASTE is that most important of low budget indie movie debuts-it makes you completely forget its budget because you've gotten lost in the story, laughs, and ingenuity

FIRST FILM FIREWORKS #8: BREATHLESS (1960, dir Jean Luc Godard) Before Godard's BREATHLESS most movies followed a set of rules in camera placement and editing to make sure that you weren't made aware of the filmmaking process itself. Godard shattered all that. In BREATHLESS and almost all of his 1960's output through WEEKEND, Godard has characters break the fourth wall, reference the camera. Godard switches lenses or aspect ratios, makes abrupt very noticeable cuts, plays with the soundtrack. He is constantly pointing out that you're watching a movie in which the elements of cinema can be manipulated at a whim. BREATHLESS tells the story of handsome petty criminal Michel (Jean Paul Belmondo becoming a star) and his American journalist girlfriend Patricia (the mysterious ultra modern Jean Seberg) across a few tense days as Michel hides out from the cops. This pulpy premise was developed by Francois Truffaut and Claude Charbol but Godard uses it more to explore the history of cinema, to set up shockingly (for that time) intimate unadorned scenes of couples' sexuality, and to introduce a whole new vibrant, vital, jazzy style. The camerawork (by master cinematographer Raoul Coutard) is mostly handheld. There is little lighting. The movie shoots completely in real apartments, real streets, real locations. Godard uses a documentary technique of "jump cutting" (cutting parts of the same shot out so everything appears to "jump" a bit since it's the same camera position and same shot) to give the whole movie a kind of jazzy be-bop feel. Godard also admitted it was the only way to get right to the good parts. You just have to be okay with a cut the audience will notice. This simple willingness to break a "filmmaking rule" opened a gateway to a whole new freedom in making movies. Filmmakers from Martin Scorsese to Richard Lester to Steven Soderbergh to Quentin Tarantino have been inspired by Godard to try things in their movies more timid souls wouldn't even dare. Godard even improvised most of the dialogue on the day of shooting so that the actors have a refreshing "realness" to their performances (they'd only just learned their lines). Godard gave cinema permission to try anything if you were willing to experiment with juxtopposing sound/image/music. If you've ever made a movie and made a thrilling discovery like running a shot backwards but playing a lion roar on the soundtrack or cutting across five different takes of a close up to a pop song, you get at the some of the essence of what makes a Godard movie so exciting. Godard would go on to make (in this programmer's opinion) even greater movies that take huge experimental cinematic risks (CONTEMPT, A BAND A PART, ALPHAVILLE, MY LIFE TO LIVE, MASCULIN FEMININ to name just a few). And, one feels compelled to acknowledge that his contrarian restlessness and intense attachment to movements of the moment would lead him to make several career left turns (not all wonderful, again in this programmer's opinion). But still, when all the dust settles, Godard broke cinema into a thousand pieces and encouraged daring moviemakers not to necessarily re-assemble them in the pre-ordained jigsaw structure. If, as Capra said, the cardinal sin of filmmaking is being boring, Godard shows the adventurous moviemaker countless new ways to generate real stylistic excitement.

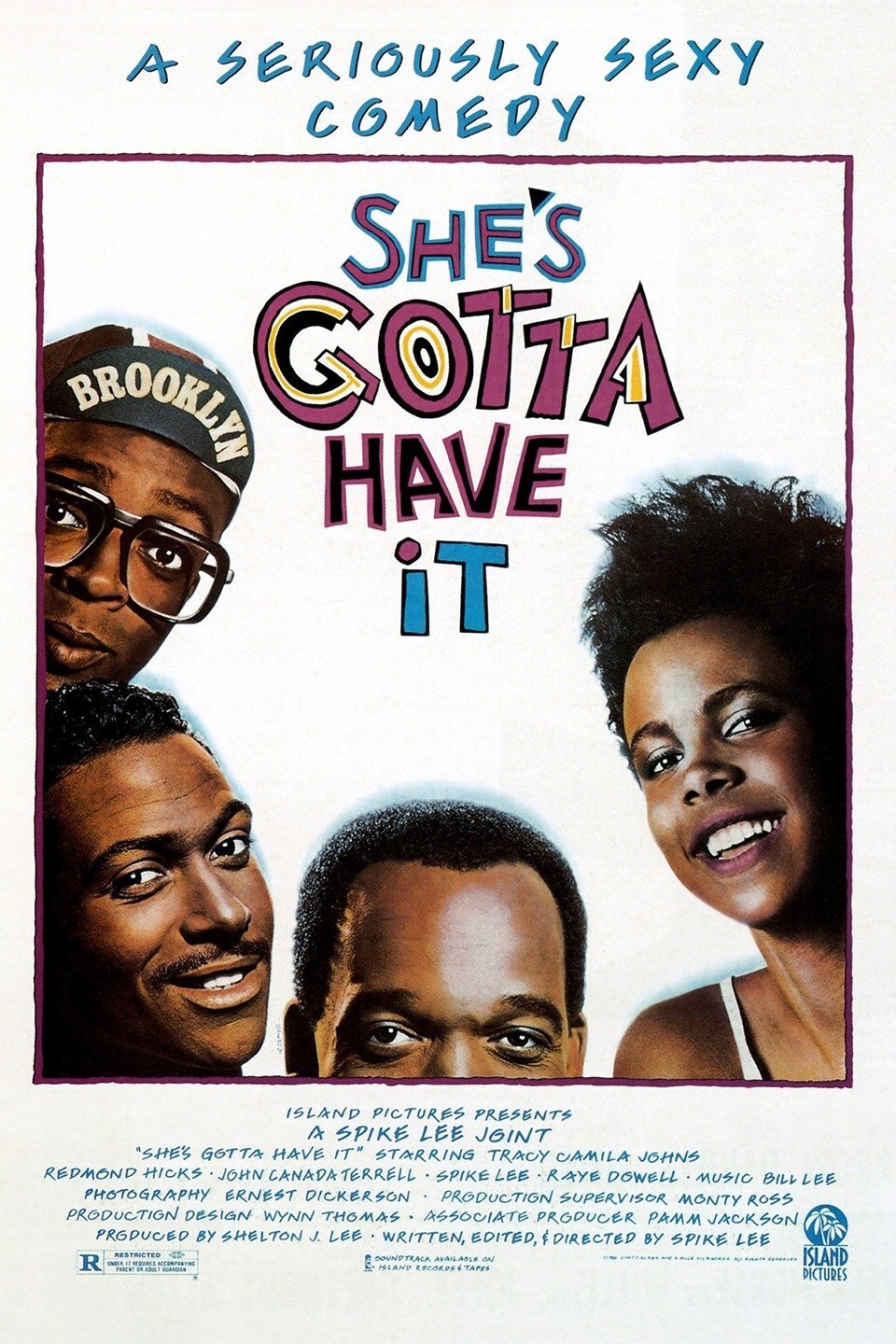

FIRST FILM FIREWORKS #7: SHE'S GOTTA HAVE IT (1986, dir by Spike Lee) Spike Lee's debut feature is what filmmaking determination is all about. Lee graduated NYU film school then spent the next four years hustling, having projects fall through, before finally grinding out this feature movie that would announce his talent, voice, vision to the world. The movie follows Nola Darling, an independent Brooklyn free spirit artist dating three men, as she narrates her frustrations with the obvious double standards that exist in the world. Men who have many sexual partners are called studs. Women who have many sexual partners are most certainly not. Shot in economical yet gorgeous black and white by master cinematographer Ernest Dickerson (who would provide much of Lee's visual language through MALCOLM X), SHE'S GOTTA HAVE IT is mostly a fun, breezy, French New Wave like comedy powered by great film sequences, frank sexuality, and tons of laughs. Many of these are provided by Lee himself as motor mouthed Mars Blackmon, one of Nola's suitors. While some of the movie's sexual politics haven't aged amazingly (Lee even recently re-booted the movie as a TV series to address some of these issues), its central strengths are stronger than ever. Lee makes a movie that celebrates black sexuality, entrepreneurship, culture, life and declares with an exclamation point that there should be more movies like this. Lee of course has gone on to make some of the most engaged, challenging, vital movies about the black experience in America since-MALCOLM X, HE GOT GAME, CLOCKERS, BAMBOOZLED. Here, in this first movie, we see a filmmaker with the courage, confidence, and creativity to cut through all the noise and make an audacious first work of art.

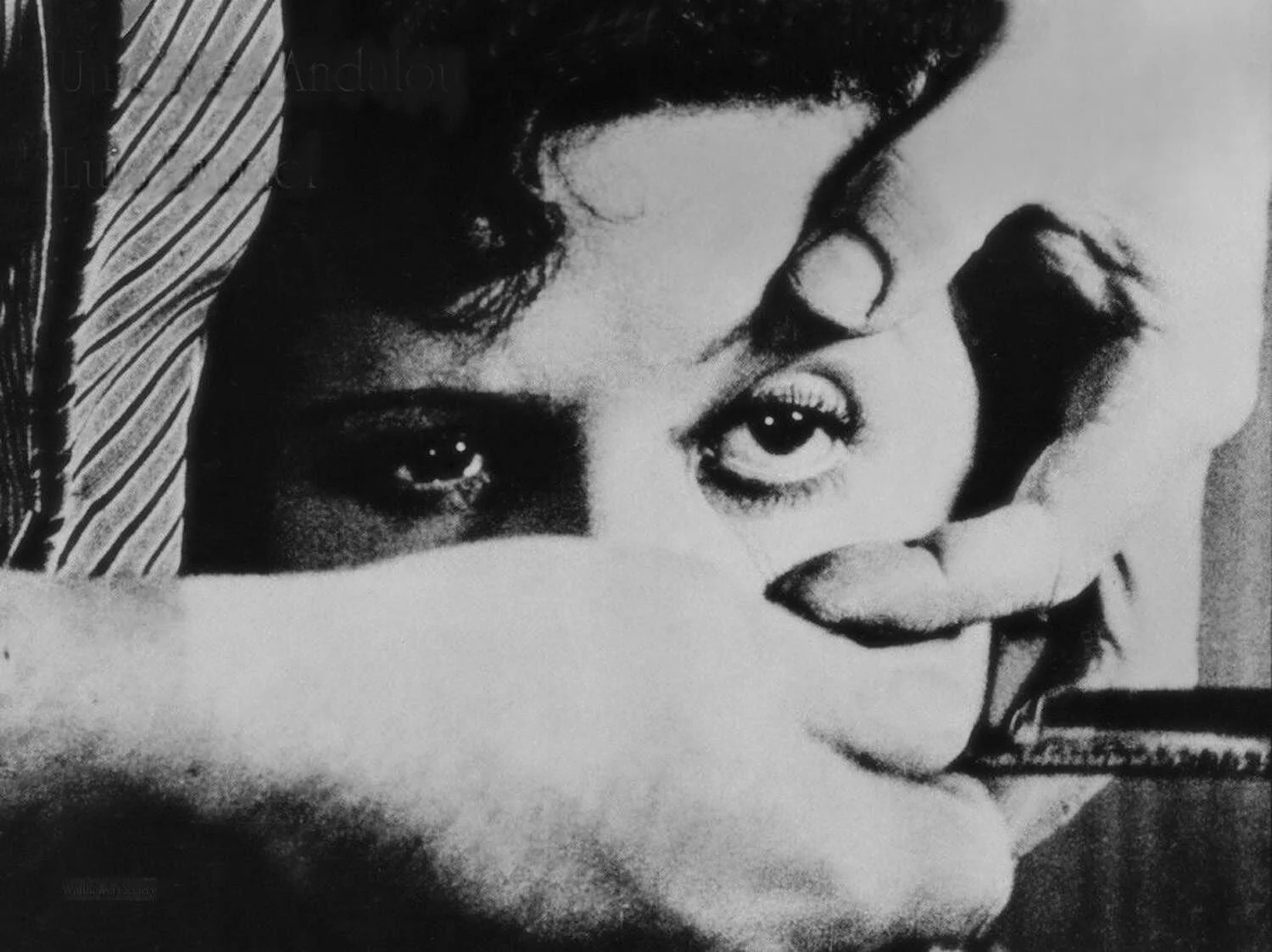

FIRST FILM FIREWORKS #6: UN CHIEN ANDALOU (1929, dir by Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dali) This surrealist short film made in Paris at the end of the 1920's could effectively be seen as the great grandparent of the cinema of David Lynch, David Cronenberg, Guy Maddin, Terry Gilliam, and others. But of course, it's also the first film of all-time great Spanish moviemaker Luis Buñuel. The short which follows a woman and man in scenes connected by a kind of surreal dream logic (the idea came from two dreams Buñuel and Dali had), was absurd enough to obscure its very real hard hitting attacks on "mainstream" societal norms. Buñuel and Dali poke fun at religion, sexual repression, gender norms, and all the boogeymen neuroses that burdened the 20th century European psyche. But, as with so much of Buñuel's greatest work, the most striking moments are the most irreducible. Like this world famous image where a man (played by Buñuel himself) appears to slice through the eye of the female lead (it was actually a dead cow's eye in close up) which is intercut with clouds "cutting" through the moon. Who knows what that means but its powerfully shocking. Buñuel, along with Fellini and David Lynch, has been one of cinema's filmmakers most comfortable with letting dream imagery and moments speak for themselves. This trust in the power of something that might not make logical sense yet makes some kind of subconscious sense is one of the greatest tools a moviemaker can have. Film rejects didactic overexplanation like a contagion. Movies just aren't meant to explain everything to the viewer with a heavy hand. Here with UN CHIEN ANDALOU, we see a very young yet confident moviemaker make the first discoveries that would power his later greatest work. Buñuel would find ways to include surreal sequences in his later narrative driven work while also telling powerful, often socially vital narratives. There may be no other moviemaker in the history of cinema who was able to marry dream logic and social critique as perfectly as Buñuel. His style reached its apex (in this programmer's opinion) with his two early 1960's classics VIRIDIANNA and THE EXTERMINATING ANGEL. With UN CHIEN ANDALOU, he put future moviemakers on notice that the closer cinema gets to dreams, the closer it gets to the source.

FIRST FILM FIREWORKS #5: Shadows (1959, dir John Cassavetes) John Cassavetes is the Shakespeare of independent American cinema. And it's ironic in a way because often times the characters in his movies are volcanos of inarticulate immediacy. Cassavetes' debut feature (made while he was starring in a succession of TV shows and crime movies) focuses on Leila, a New York black woman passing as white, her affair with white Tony, and her relationship with her much darker skinned brothers, Hugh and Ben. While the movie definitely explores issues of race, it also (like all Cassavetes' movies) defies your expectations by zealously avoiding the cliche. Cassavetes has the audacity in the 1950's to focus as much on the lives, dreams, romances, free time of his characters as their internal conflicts. The whole movie bounces and bumps with the rhythms of a be-bop beatnik house party. We spend as much time with the characters goofing around as we do with them at moments of ultimate crisis. Cassavetes even devotes a long section of the movie to older brother Hugh's struggles with his singing act and the compromises he needs to make to get booked into clubs. Cassavetes never felt the obligation to be bound to Hollywood storytelling tropes. Instead his movies pulse with the lifesblood of real existence and a singular commitment to character development. Scenes often veer from dramatic to comic within seconds and back again. And Cassavetes' strange style of combining very written scenes (he was a tremendous writer) with scenes developed out of improvisation always keep you off balance as a viewer. In the end, a Cassavetes' movie always reminds you that you're alive, you're imperfect, and that's okay. And while later movies like FACES and A WOMAN UNDER THE INFLUENCE would attain even greater heights, the audacity to love his characters and let them be imperfect souls trying their best that we see in SHADOWS sets the template for one of the most inspiring careers in all of cinema.

FIRST FILM FIREWORKS #4: PATHER PANCHALI (1955, dir by Satyajit Ray) This movie from Bengal, India launched the career of one of cinema's most committed, talented filmmakers of integrity. Satyajit Ray was all ready well into a successful career as an illustrator when he took on this adaptation of a beloved children's novel about mischievous boy Apu born into a poor rural yet deeply artistic and educated family. It follows his adventures and tragedies as he experiences them with his mother, father, sister, and elderly Auntie. Satyajit Ray invested so much of his own money to make the movie that eventually his wife had to sell all her jewelry so they could keep going. It was only at the very end of production that the Bengali powers that be realized what an incredible film Ray had made and provided the finishing funds to complete it. PATHER PANCHALI (which translates as "little song of the road") is one of those rare films where style, substance, emotion, philosophy, and profound insight into the human condition all fuse into one overpowering experience. It's also one of the rare movies where you will gasp, laugh, marvel, and weep in equal measure. Like so many other first filmmakers, Ray had only his commitment to cinema, belief in himself, and vision that the project could be something to sustain him through the years of sweat and toil. But once he broke through the gates, he was able to make incredible movies at roughly a pace of one a year for the next 30-40 years. PANCHALI became the first of a trilogy of movies (all made from 1955-1959) that follow Apu from boyhood to adolescence (APARAJITO) to adulthood and fatherhood (THE WORLD OF APU). The three movies together chronicle many of life's greatest rites of passage. Ray pulls off that hardest of accomplishments: by being very specific (looking at the life of a Bengali in the mid 20th century) he creates an overpowering work of universal import. Producing great cinema like producing anything great appears to take equal parts talent, determination, experimentation, humility, ability to grind it out until it's right. Satyajit Ray crafts sequences of tremendous cinematic power that also blossom with emotional insight. Akira Kurosawa said "Never having seen a Satyajit Ray film is like never having seen the sun or the moon." Seek out these movies. See the stars.

FIRST FILM FIREWORKS #3: ERASERHEAD (1977, dir by David Lynch)If ever there was argument that cinema is an "experience", David Lynch's ERASERHEAD is it. A Man meets his Girlfriend's Family only to find out his Girlfriend is pregnant. But when she gives birth, the Baby is deformed. The Man begins to lust after a neighbor in his apartment. A Woman in his radiator begins to sing about heaven. It's almost pointless to try to write a summary of ERASERHEAD because it has so much going for it than even these absurd story points suggest. It's hilarious and horrific simultaneously. The lighting, production design, baby effects, and cinematic sequences are mind boggling. Lynch spent over four years on this project. His family tried to convince him to give it up. Many on the crew chipped in money to keep it going. Lynch eventually got a pre-dawn paper route to support his family and the movie. Long after many of the most expensive movies of its day have been forgotten, ERASERHEAD is continually discovered by new generations. David Lynch set a template here that he has admirably followed for his 40+ year career since: put your heart and soul into making the movie, be as true as possible in creating the best possible work you can, trust the audience to figure out what the movie means. And while Lynch's movies can be wildly, willfully head scratching, there is always a THERE there. In some ways that's the secret sauce. If you let the movies communicate with your heart and soul and subconscious, you KNOW they're about something profound even if it isn't always immediately understandable. If you demand that everything have an easy explanation, you're in for some tough times with Lynch. But if you're looking for cinema that wrestles with the biggest issues, you've come to the right place. ERASERHEAD shot in stunning black and white by Frederick Elmes with singular sound design by Alan Splett, tremendous performances especially by lead Jack Nance is one of the biggest arguments for patience, excellence, and commitment to vision. Cinema has produced few truly singular artists like David Lynch. Thank God he's found a way to make movies for almost 50 years.

FIRST FEATURE FIREWORKS #2: BLOOD SIMPLE (1984, Coen Brothers) In many ways, BLOOD SIMPLE both foreshadows and in no way prepares you for the trajectory of the Coen Brothers' incredible near 40+ years in cinema. On one hand, it is a Texas noir of supreme style. On the other hand, it's such a pitch black comedy it doesn't quite prepare you for the strange humanism that will bubble up in works like RAISING ARIZONA or THE BIG LEBOWKSI or the tremendous philosophical daring of works like BARTON FINK or A SERIOUS MAN. And yet, it is supremely Coens because it has such a confident sense of what it is. Modeled after James M. Cain's hard boiled style, BLOOD SIMPLE (which is a term to refer to someone not super bright) follows a Bartender who starts up an affair with his Boss's Wife only to have the Boss hire a Private Detective to kill the lovers. Through a series of misunderstandings, each character comes to believe they've been double crossed by all the other characters. This leads to one of the pitchest black comedic endings this programmer has ever seen. A midpoint night sequence where the Bartender tries to bury the Husband (who has survived a point blank gunshot) in the middle of a Texas field is a symphony of sound, imagery, and character motivation. The Coens shot a sizzle trailer then raised money from their parents' friends to make this feature on a shoestring budget. They borrowed some camera techniques from their friend Sam Raimi (whom Joel had worked with as assistant editor on EVIL DEAD) but also came up with startlingly brilliant imagery of their own. Ever since, the Coens have rigorously been documenting American life through genre and philosophical investigation. In a funny way, you could almost put together Coen Brothers' movies to tell a kind of perverse American history in the same way you could take John Ford movies to tell a version of American history. But in Coen Brothers' movies, there's almost always a sense of a malevolence (sometimes external, often internal) that must be reckoned with married to an ironic understanding of humanity's many-splendored hypocrisies. As the Coens have developed as moviemakers possibly what's most surprising is how they've retained their ridiculous talent for bold style while deepening their philosophical outlook to embrace what may actually be an acknowledgement of something mysterious and transcendent.

FIRST FILM FIREWORKS #1: SANSHIRO SUGATA (1943, dir by Akira Kurosawa) Akira Kurosawa's debut feature (which he wrote and directed) is one of the most assured first movies of all history. Kurosawa cannily chose to make a commercially desirable martial arts movie that focuses on Sanshiro, a 19th century talented but stubborn youth who discovers the martial arts form Judo. The movie is a muscularly entertaining story of the talented upstart who has to learn humility to really become a master. While the movie was made during World War II and Kurosawa has often said he felt circumscribed until studio Toho finally gave him complete creative control on DRUNKEN ANGEL (1948), SANSHIRO SUGATA is clearly and undeniably a Kurosawa film. The scriptwriting, storytelling, editing, already apparent mastery of film elements are all here. Even more, from the first Kurosawa understands the power of a sequence to wordlessly distill a movie's themes to their cinematic essence. Here, Sanshiro accepts the punishment of his master and spends an evening up to his chest in a freezing swamp. He grasps only a strong bamboo shoot for support. Kurosawa devotes a surprisingly long amount of time to just observing Sugata in this swamp move from anger to willful defiance to regret to pain to dawning realization to humility. It's a sequence any other director would be proud to have on their "hits reel" at the end of their career. This is a sequence in Kurosawa's first movie. Although Kurosawa would go on to create works that would place him near or at the very top of the filmmaker firmament, SANSHIRO SUGATA already has him gliding along the lithosphere. This is a movie of someone who clearly devoted themselves to understanding the fundamentals. Nobody, before or since, has shown as strong a mastery of every element of cinema as Kurosawa-san.

Written by Craig Hammill. Founder.Programmer Secret Movie Club.