DEATH CLOAKED IN GENRE: The Coen Brothers’ No Country for Old Men by Craig Hammill

No Country For Old Men (2007, adapt & dir by Ethan & Joel Coen, from the Cormac McCarthy novel of the same name, starring Josh Brolin, Javier Bardem, Tommy Lee Jones, Kelly MacDonald, Woody Harrelson)

SPECIAL NOTE: This piece inaugurates an occasional series of longer form film pieces. Every now and then, Secret Movie Club will take a deeper dive/look into a movie, moviemaker, aspect of movie culture. There will be more research, trivia, behind the scenes, facts about the work/artist/aspect of cinema culture we’re exploring. Let us know what you think and what you think we can do better.

It has been seventeen years since the Coen Brothers’ adaptation of Cormac McCarthy’s novel No Country For Old Men opened in movie theaters in 2007 and the movie feels like it is gaining in power and importance.

It was hailed as a return to form masterpiece from the get-go by critics. The Coens had just made Intolerable Cruelty (2003) and The Ladykillers (2004) back to back; two movies often considered pretty minor in the Coens’ formidable body of work.

No Country would go on to win 8 Academy Awards besting Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood at the awards ceremony.

This bloody, unsettling, and, for many first viewers, puzzling movie is also one of the Coens’ highest box office grossers (with $171 million worldwide) second only to another Coens’ western adaptation True Grit ($252 million worldwide).

What makes No Country For Old Men even more of a puzzler is that it is clear it is the child of two distinct strong sensibilities: it started as a screenplay by novelist Cormac McCarthy who then turned it into a terse novel published in 2005. The Coens then came on to adapt it BACK into a screenplay and movie for a 2007 release.

While the violent, brutal, sometimes over stylized philosophical sensibility of novelist Cormac McCarthy and the humorous, dark, sometimes over stylized, philosophical sensibility of the Coen Brothers overlap in key ways, they are also distinct.

More important, the Coens had staked out an entire career of almost all original screenplays. So there’s an irony that the one time their movie making received universal critical acclaim, it was for an adaptation.

Still, you could always see the book readers’ influence in their work. Miller’s Crossing (19990) is a reconfigured variation on classic pulp novelist Dashiell Hammet’s novel Red Harvest. The Big Lebowski (1997) is a tribute to both Raymond Chandler noirs and Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye (itself a Chandler adaptation). Even a movie like Barton Fink (1991) is about a Clifford Odetts’ type playwright who interacts with a William Faulkner type novelist in Hollywood.

So it’s possible that the Coens were well prepared to adapt someone else’s novel with the confidence that they could still find personal meaning and expression and differentiation in their adaptation.

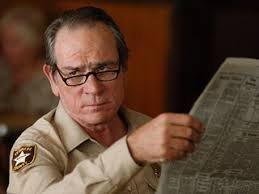

No Country For Old Men follows Texas everyman and Vietnam vet Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin) who decides to take a briefcase of $2million dollars he finds in the Texas back country at a drug deal gone wrong (everyone else is shot dead or dying). Relentless sociopathic fixer Anton Chigurh (Javier Barden in the performance that won him the Best Supporting Actor Oscar) tracks Moss to get back the money. Aging sheriff Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee Jones) is close behind in solving the mystery as the bodies pile up.

The movie could almost be considered the third entry in the Coen Brothers’ brutal regional genre series that includes their 1984 debut Blood Simple and 1996 Fargo. It’s fascinating to note that the Coens chose a brutal violent noir as the best vehicle to break into filmmaking. And ever since, if they feel they need to re-set, they return to an American regional genre picture that focuses on unsettling violence and crime. Fargo was their re-set after the relative misfire of The Hudsucker Proxy. No Country was a kind of re-set after two movies that had people thinking the Coens had lost a step.

Maybe it’s no surprise that now, in 2024, Ethan Coen has stated that after a six year hiatus making movies apart, the Coens are re-uniting for a pure horror movie he likens to a variation on Blood Simple.

What may make No Country For Old Men so powerful, a power that feels like it’s growing to this writer, is how mysterious it ultimately is. That being said, it is also paradoxically fairly plain spoken and direct about at least one of its key themes: death.

If you’ve seen the movie, you know how its twists and turns often surprise and confuse first time viewers. There is also a clear metaphysical, philosophical drive to the movie that centers around themes like chance, free will, determinism, the existence or non-existence of God, and the possibility that if there is a transcendent force to the universe it may be one of unrelenting destruction, violence, and indifference rather than forgiving, non-judgemental, beneficent creation.

The movie and source material don’t pretend to offer definitive answers to these questions. Instead, like so many great cinematic works of art, No Country raises and explores the questions but ends in a way that lets the viewer continue to wrestle with the possibilities.

This gripping violent Neo-Western also acts as a Rorschach test for viewers. Those inclined to believe in a spiritual/transcendent level to the universe may yet, despite all its seeming nihilistic brutality, find what Herman Melville called “shoots of divine intuition” in the movie. Agnostics and atheists inclined to reject any kind of transcendent universal organization based on the lived experience of life’s brutality, violence, randomness, senselessness will also find plenty to support their world view.

So that, in that strange way that great art functions, the always dynamic and warring viewpoints feel like they fight their way to a draw. . .for the moment.

NO COUNTRY’S PURE CINEMA & STRUCTURE

Ye of Little Dialogue

One of the key aspects of No Country is its spareness with dialogue for long stretches. While this is almost certainly a Cormac McCarthy trademark, the Coens had put aside a planned adaptation of James Dickey’s World War II novel To The White Sea in the early 2000’s which may have influenced their approach here. The To The White Sea script was famous for how its lead character (who was to be played by Brad Pitt) spoke almost no dialogue the entire movie since he was behind enemy lines in Japan.

Though there are key heavy dialogue scenes later in No Country For Old Men much of the first half has long passages where there is little or no dialogue.

The Coens talked about how French austere moviemaker Robert Bresson (A Man Escaped, Diary of a Country Priest) was a big influence on No Country For Old Men. Bresson also tackled big metaphysical subject matter. But he worked to do it in a very procedural, focused, simple way.

Doubling

Often the height of cinematic artistry is its obfuscation. We don’t notice that the most amazing “oner” in Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil is actually the planting of dynamite in the boyfriend’s apartment at the midpoint of the movie (rather than the flashier opening tracking shot).

We only realize it after a few viewings.

The reason for this may be that movie making at its pinnacle is so absorbing, like a powerful dream, that the craft becomes one with the story. Form and content become one and the same.

It’s amazing by one’s third or fourth rewatch of No Country For Old Men to see how many cinematic doubling strategies are employed right out in the open.

Very early in the movie, our antagonist psychotic killer/force of nature Anton Chigurh puts a cattle gun to a stunned driver’s forehead and says “Hold still please.”

The Coens then cut to our hero Llewelyn Moss zeroing in on an antelope through his rifle scope and saying basically the same thing before shooting the animal.

Immediately, the movie is telling us that, in some way, Chigurh and Moss are the same. Both are killers. Both are hunters. Both bring death to those around them. They are connected in some way we the audience should understand even if they, within the story, do not.

This doubling strategy happens so many times in the movie, it’s ridiculous. During Chigurh’s and Moss’s midpoint movie shoot out, they both injur but do not kill the other. We then see Moss have to rest up at a Mexican hospital and Chigurh basically do surgery on himself in a hotel room. They both have to convalesce. They both have affected the other. In THE SAME WAY.

The Coens also devote longer than necessary shots to both Moss and Chigurh stripping off bloody white socks in doubling shots.

One doubling device that’s so out in the open it’s invisible is that BOTH Moss and Chigurh run into groups of adolescent boys or young college men when they are most hurt. Both ask for articles of clothing. Both pay for them with bloody money.

Other instances of doubling pepper the movie.

In the hospital, Moss is visited by hired clean up man Carson Wells (played by Woody Harrelson). It turns out they’re both Vietnam vets. Wells, in fact, we learn later, is a retired colonel. “Is that supposed to make us buddies or something?” Moss asks tersely.

Maybe not. But what it does do is establish that Moss, Wells, Chigurh, Bell all have been drafted into or chosen professions or periods of life where they were surrounded by death, destruction, murder, the ends of things.

Another strange moment of doubling occurs when Moss attempts to kill an antelope at the beginning of the movie and only seems to wound it in its haunches. The animal manages to stumble away with its herd. Moments later, Moss trying to track the animal looks in the distance and sees another animal hobbling. Only it’s not the grazed antelope but a grazed dog. This dog stumbles on its own wounded haunches to get away.

We soon learn the dog is running away from a drug deal gone wrong that starts in motion the whole story. Like so many things in the movie, this transference from one animal to another doubled animal is mysterious yet somehow crucial to the force of the movie.

Abstraction

Cinematically, the Coens prep us for the dawning realization that Chigurh may be something more than a psychotic killer, he may be a transcendent force of nature, with shots that turn Chigurh into an abstraction.

When Chigurh visits the Moss’s trailer home, he looks at himself, silhouetted in the glass of the turned off television set. Sheriff Bell looks at himself silhouetted in the same television set a few scenes later. Again doubling AND abstraction. But also connection: Chigurh and Bell are now connected, associated with one another.

Later we see Chigurh abstracted into circles in the early 80’s yellow glass of a door.

Moss later sees Chigurh as a silhouette in the store front glass during their only real in person confrontation.

Later Sheriff Bell abstracts Chigurh verbally by calling Chigurh a “ghost”.

Chigurh is almost always framed as Death incarnate.

The Coens also convey Chigurh’s wraith like qualities when Sheriff Bell senses Chigurh’s presence in the hotel room where Moss has been killed (by Mexican Narcos NOT Chigurh). We see Bell outside the door. The Coens then cut to a strange shot of Chigurh waiting INSIDE the room in the darkness.

But when Bell draws his gun and enters Chigurh is gone. And the only other escape, a bathroom window, is shown to be locked from the inside negating that escape.

So was Chigurh there? And if he was, was he somehow able to move through walls? Is he, in fact, some kind of otherworldly thing? The violence of the universe made incarnate and flesh? Death itself. The Grim Reaper turned into an early 1980’s hired killer with a strange haircut?

Free Will, Determinism, and Chance

These themes run rampant in No Country For Old Men. But again, they’re so obvious as to be paradoxically invisible.

Llewelyn initially leaves a dying Narco at the site of the drug handoff run amok to die in the night. Moss dismisses the Narco’s request for water.

But Moss is troubled by his own callousness and returns to the site that night with a gallon of water for the Narco.

This is one of the most mystifying decisions ever. For as resourceful/lucky as Moss is for most of the movie (until he isn’t), he’s certainly not stupid enough to really believe this is a good decision.

So why does he go back, knowing he is almost certainly tempting fate?

We get the sense it is because Moss has a conscience. Chigurh has “principles” but certainly no conscience as we would understand it. It may be this conscience that makes Moss mortal. And this lack of conscience that makes Chigurh some kind of immortal.

But the meaning here is again mysterious. Sheriff Bell ALSO clearly has a conscience. And he too makes a decision to confront Chigurh when Chigurh appears hiding in the hotel room. But Bell lives. Moss does not.

Sheriff Bell seems to have a healthy appreciation for the fragility of life and omnipresence of danger and death. In a sense, Bell is humble before these things. Though he does must the courage to confront them. Moss, on the other hand, has a kind of cavalier cowboy attitude towards death and danger. We admire Moss's grit and courage to take on Chigurh. But we also notice that Moss has a tendency to make "unwise" decisions. Moss takes two million of drug money without seeming to think the criminals owed that money can catch him. Moss thinks he can take on Chigurgh without any aid or backup or support. Again something that we, as the audience, know is ill-advised. Moss, ultimately, is NOT humble before death and danger. And he pays the ultimate price with his life.

When we dig down deeper, we realize that the initial decision Moss makes to take the $2 million dollars of drug money is almost certainly the decision that condemns him to his ultimate fate (gunned down by drug Narcos).

All his decisions after that may keep him momentarily one step ahead of death and the violence of Chigurh but it is Moss’s understandably human but clearly poor choice to take drug money that is not his that seals his fate.

And it is a choice. Still, who are we to judge? Who among us would be able to pass up $2 million? Only the strongest willed and most clear eyed of us.

So again, CHOICE and FREE WILL do play a part here. But it’s hard to harness them when so many of us are corrupted by greed, sloth, those nasty seven vices.

Then there’s chance. As opposed to free will or determinism.

Chigurh seems to have a more profound understanding of the role of chance in existence than any other character. This is represented by his habit of flipping a coin and asking his victims to “call it”. Chigurh has some kind of strange integrity and respect when it comes to chance.

When the gas station owner calls “heads” correctly, Chigurh lets him live. When Carla Jean Moss, Llewelyn’s wife, refuses to call the coin, Chigurh kills her. He seems to punish people who refuse to acknowledge the role chance plays in existence.

Or who refuse to engage with chance.

The mysterious interplay of these fundamental, seemingly oppositional forces, is never resolved in the movie.

How could it be? It’s never resolved in life.

Yet all the characters seem, at different times, to make choices of their own free will, to be guided by some kind of invisible hand of fate, or blindsided by chance.

Subversion of Structure/Celebration of Structure

Probably the biggest surprise to first time viewers is the random death of Llewelyn Moss offscreen while the movie still has twenty plus minutes to go.

The movie, a neo-western, has set us up to expect a “showdown” between Chigurh and Moss. We want that show down. We want a final answer, one way or another, to who is stronger.

At the very least, when Llewelyn’s Mother In Law unwittingly tips off the Narcos to Moss’s whereabouts, we want to see that confrontation.

But we don’t. We only see its aftermath.

What’s interesting here is that Carla Jean, Llewelyn’s wife, almost saves him. She asks Sheriff Bell to go to the hotel out ahead of her. Bell rushes there. And he is only late by minutes. Had Bell somehow been able to arrive twenty minutes earlier, who knows? Moss may have lived. Or maybe both Moss and Bell would be dead.

When you see the movie several times, you actually realize the “offscreen” murder isn’t actually so offscreen. We really only miss the actual shots fired. But we see everything just before and everything just after.

It’s as if to remind us of the role of chance.

This subversion of structure frustrates A LOT of people.

What’s funny though is how so many of us don’t realize the Coens and McCarthy actually DO give us the showdown we wanted. The duel.

They just put it in the middle of the picture instead of the end.

The rest of this sequence is even doper than this very dope still.

Arguably the most amazing sequence of the movie (and one of the best in the whole Coen canon) is the shoot out between Moss and Chigurh in the middle of the picture. Moss realizes there is a tracking device in the briefcase of money. Moments later, he HEARS the tracking device outside (Chigurh has the responder).

This leads to an extended shoot out both inside and outside the hotel that ends in a draw with BOTH Moss and Chigurh wounded but not dead.

How clever to hide such an obvious metaphor by putting it in the middle of the movie rather than the end.

In fact, its structural placement in the MIDDLE of the movie reinforces thematically the notion that these universal oppositional forces are always at battle. Have never been able to fully overwhelm the other. Are always fighting each other to a draw.

Though Moss does ultimately die, Chigurh does not “triumph” unscathed. In the second to last scene, he is broadsided in a car accident and seriously wounded. Though we see him hobble away (probably to terrorize another day), he is able to be hurt, slowed down, wounded.

He also can be a victim of the same chance he worships like a religion.

Certainty, God, Non-certainty

The concept of “certainty” and “uncertainty” pop up several times. Most notably in the tense exchange between Anton Chigurh and Woody Harrelson’s Carson Wells (just before Chigurh kills Wells).

When Chigurh states he doesn’t need Wells’ help retrieving the money that Moss has because the money will be “deposited at his (Chigurh’s) feet”, Wells says, “You don’t know that for a certainty.”

“I do know that for a certainty,” Chigurh replies. The exchange is strange because Chigurh seems to understand exactly what Wells means: that no one knows how anything will turn out.

Chigurh’s chilling response seems to go beyond bluff or cockiness. Somehow, Chigurh implies, he (Chigurh) does know these things even if mortals like Wells do not.

Like so much in the movie, the meaning of this exchange probably boils down to the beliefs of the audience member. Chigurh does seem to get the money as he said he would (though we never see Chigurh ACTUALLY retrieve the money. It is implied).

So this writer can only say that while, on one hand, Chigurh is correct-he does get the money-the totality of his statement still seems up in the air by movie’s end. Chigurh finally is a kind of demon, force of nature, the second law of thermodynamics-everything falls apart. But he is still somehow subject to even bigger laws even he (Chigurh) does not fully understand. His car accident at the end and his stumbling away seem to point to something even bigger than him.

While Chigurh embraces chance, he is also a victim of it.

This leaves us with the conundrum of Sheriff Ed Tom Bell played with equal parts fear, humour, courage by Tommy Lee Jones.

The movie is ultimately a triangle between Moss, Chigurh, and Bell as each character hunts, pursues, or seeks out the other.

Bell is unable to prevent Moss’s death or capture Chigurh. But Bell does survive, the only main character who seems able to extricate themselves from a cycle of violence. And he does pursue the case, though unwillingly, with integrity and courage.

Late in the movie, Bell visits his Uncle Ellis who is confined to a wheelchair as the result of a shoot out when Ellis was a lawman himself. Bell laments that God never really declared himself to Bell. But Bell adds, he doesn’t blame God as Bell doesn’t think himself worthy.

This leads to one of the most important moments in the movie but again is obscured by the artistry of the performers, the moviemakers, the script.

“You don’t know what he (God) thinks,” Ellis responds.

Bell doesn’t seem to fully understand or take in that both he and Ellis have affirmed the existence of God in their own way AND affirmed that the nature of God is ultimately at the heart of mystery. So much so that one can both acknowledge and be uncertain about God at the same time.

Death and after…

Ultimately, the movie, like so many great movies, is about death. No Country For Old Men is a movie haunted by, suffused with, permeated through with death.

There is no escaping it. There is no understanding it. It comes for us all. We have no idea when it will finally lay us flat. And we have no idea what comes after it.

In the final scene of the movie, Bell recounts two dreams to his wife. Both center around Bell’s father, now long dead. Bell points out the irony that since his Dad died in his forties, his Father is now, in many ways, “the younger man”.

In the first dream, Bell’s Father gives him money and Bell loses it. In the second, Bell’s Father and Bell are on horses. Bell’s Father has a horn filled with fire and rides up ahead into the darkness to start a fire. Bell somehow knows he will meet his Father again at that fire and his Father will be waiting for him. A light in the darkness.

“And then I woke up,” Bell says. And then the movie cuts to black.

I want to write more here but I feel it presumptuous and improper.

The only proper thing here is therefore to end and be silent.

Craig Hammill is the founder.programmer of Secret Movie Club.