David Bowie: The Singer-Songwriter as Writer-Director as Cinema Auteur by Craig Hammill

Last week we screened Brett Morgen’s incredible 2022 David Bowie life experience movie Moonage Daydream. You’ve probably heard it all already but Morgen was granted access to never before seen film and audio footage of David Bowie throughout his life by the Bowie estate. And he decided to take a page from Bowie and create something unique, new, boundary pushing that would embody Bowie’s essence rather than regurgitate talking heads bullet points on life facts we all knew.

Moonage Daydream may not quite be great but it is pretty damn close. And at times, it achieves the sublime. Morgen does a deft job at still communicating quite a lot about Bowie’s life, influences, and antecedents without ever making it feel like we’re watching a documentary.

As a lifelong Bowie fan, this Programmer didn’t know the mental health issues of Bowie’s older beloved brother who turned Bowie on to the Beatniks, jazz, and travelling. Nor did this Programmer realize quite how extensive Bowie’s traveling was to soak up other cultures, spiritualities, philosophies as a way of trying to expand Bowie’s understanding of his own spirituality.

Moonage Daydream plays like a kind of dream of a rock album free associating technicolor and dayglo abstract imagery with backstage footage with audio pulled from interviews, television programs, press junkets throughout all of Bowie’s life.

This Programmer watched the movie in the back row singing quietly, tapping feet, keeping rhythm. The way you should in a truly great rock doc or musical.

It’s no surprise that singer-songwriters like Bowie, Prince, and Bob Dylan all were magnetically attracted to moviemaking and cinema (either as actors, composers, writers, directors or all four sometimes).

Akira Kurosawa, among others, feels that cinema is most like music. And this Programmer agrees. So it doesn’t seem so far fetched that singer-songwriters might feel that cinema is the closest analogue to what they do when they write, record, and put together a rock album.

As I watched Bowie and realized just how many great albums he banged out in his lifetime – Honky Dory, The Man Who Sold the World, Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane, Young Americans, Station to Station, Low, Heroes, The Lodger, Scary Monsters, Black Star. . .(so many hits, so many bangers, it’s dangerous) – it dawned on me how important it is (at least for me) to keep in mind that great cinema is just like that great New York Velvet Underground avant garde street rock that Bowie so loved.

It’s not necessarily the brilliant conservatory music background that makes the genius artist, it’s the willingness to tap into that unnameable universal force, have ideas (musical ideas are just as rare and electric and important as filmic ideas), be engaged in your moment, and take a chance to express, reveal, illuminate something.

Great movies should be like great rock albums. United by conscious and subconscious rhymes, themes, attitudes, motifs. But also pulsating with that clang bang collision of melody, rhythm, songwriting focus of the moment, zeitgeist.

It’s always been fascinating to me that Bowie wrote one of his greatest albums Station to Station during one of his absolute lowest points-during his cocaine near psychosis days of shooting his 1976 Nicolas Roeg movie The Man Who Fell To Earth.

Bowie himself has talked about how he remembers very little of the actual recording of the album but how he did remember that it was a kind of plea to the universe, to God, to hook him out of the gaping void and abyss he was hurtling towards. You can feel that tension in the album. The conflict is embodied write there in the first song (and one of my absolute favorites) Station to Station where Bowie does a complete tempo/rhythm/melody shift halfway through the song from a kind of Kraftwerk Euro-dirge to a global Disco death march.

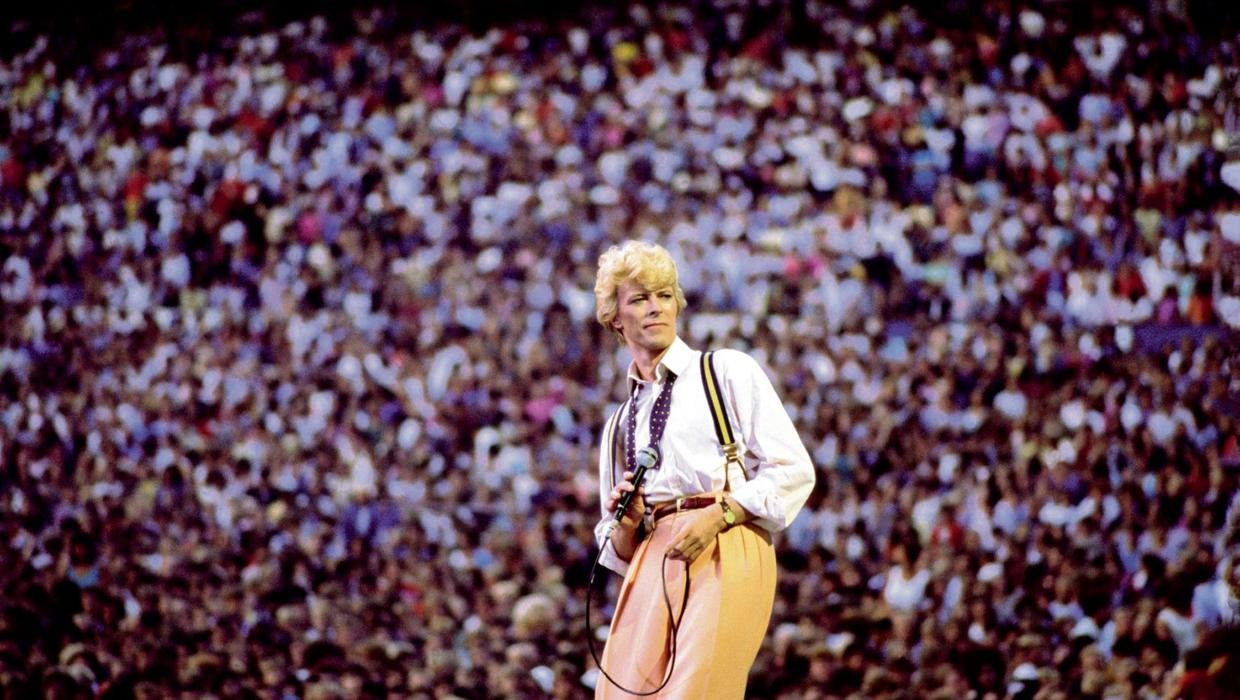

It’s also weird to parse out how sometimes Bowie’s greatest commercial successes (the Let’s Dance album and tour of the 1980’s) could represent both a step forward and a step back simultaneously for Bowie.

Filmmaker Todd Haynes based a whole movie on this (Velvet Goldmine). But I always felt Haynes take was unfair and not quite on the mark. Haynes’ movie posits that Bowie abandoned his glam genius for corporate straight jacket greed. But Brett Morgen’s illuminating Moonage Daydream shows what feels like something closer to the truth: after years of struggle Bowie wanted to come into the light, entertain, and connect with his audience.

What’s interesting though is that once he did, Bowie got restless again to move on to something different.

Anyway, this is all a long way of saying that I sense there’s something profound and earth shaking to be had for any filmmaker willing to listen to albums of the greats. You listen to a Bowie album or a Prince album or a Dylan album or hell. . .a Miles Davis album or a Thelonious Monk album and you get connected to the idea factory that makes great cinematic scenes, sequences, throughlines.

There’s such an important connection here between cinema and music. Between the singer- songwriter and the writer-director.

Maybe most importantly, is Bowie’s advice (which many of us have heard but maybe fewer of us have truly taken to heart):

“Always go a little further into the water than you feel you're capable of being in. Go a little out of your depth, and when you don't feel that your feet are quite touching the bottom, you're just about in the right place to do something exciting.”

Bowie lived that advice as his life. And it’s still humbling and fascinating to me that when Bowie learned he was going to die, he got to call his shot by making his last album one of his greatest. BlackStar is suffused with thoughts of spirituality, death, life. But it remains steadfastly an honest and truthful album.

Bowie said late in his life that he was “almost an athiest”. . .but not quite. There’s something in the tension of that statement that fascinates me. It sounds like someone who is determined never EVER to let dogmatism or inertia freeze their journey to try to see life for what it really is and the world for what it really is. Bowie would also speculate that since he had found all the cliches to be true (life goes by so fast, your family is the most important thing, use your time wisely), the cliche that God exists might also have to be true.

Is Bowie being cheeky? Maybe. But he’s also being honest. But honest in a pure way of creative exploration that this programmer finds honorable.

David Bowie. The patron saint of creative searchers.

Craig Hammill is the founder.programmer of Secret Movie Club.