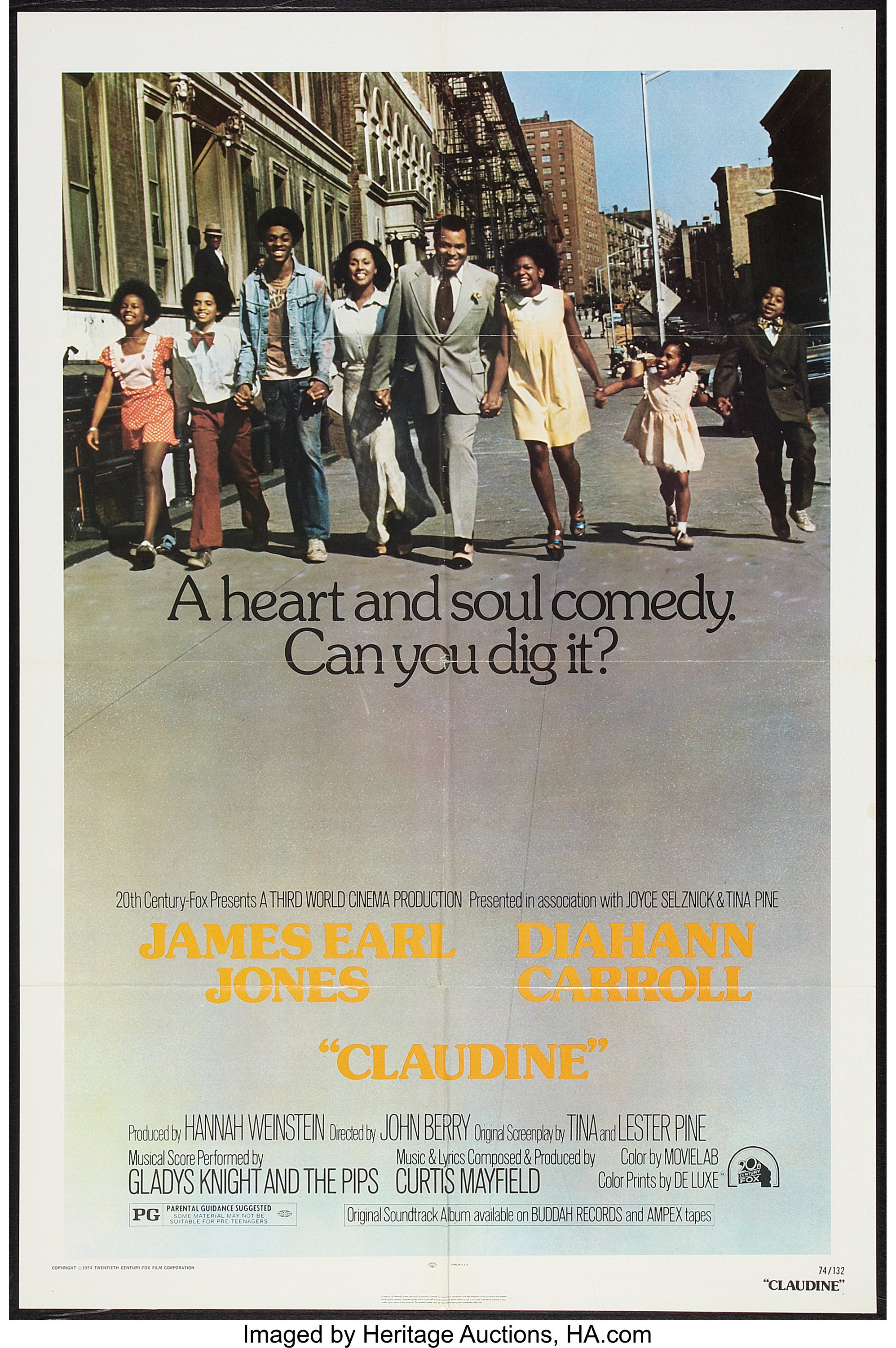

CLAUDINE (1974, John Berry, USA) An appraisal of American melodrama done right by Matt Olsen

Inner City Melodrama

Claudine (1974), directed by John Berry

There’s a certain kind of melodrama frequently associated with (and often attributed to) the 1950s films of Douglas Sirk – family-based dramas with plots driven more by the internal forces of the characters’ heightened emotions rather than narrative twists. That’s a very shorthand and, admittedly, reductive version of a description of his general approach. He also didn’t shy away from taking on potentially prickly social issues within the films’ stories, highlighting alcoholism and impotence in Written on the Wind or racism in Imitation of Life.

At the dawn of the next decade, a wave of thematically-related UK films appeared, such as Karl Reisz’ Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, Tony Richardson’s Look Back in Anger and A Taste of Honey, and Lindsay Anderson’s This Sporting Life. These stories retained many of Sirk’s melodramatic narrative aspects but traded in the lush Technicolor hues of his middle to upper class America for a stark black and white realism grounded in the young adults of England’s lower class of the 1960s. There’s a naturalistic, “life is hard” grittiness inherent in the stories that echoes in the contemporary works of heralded auteurs such as the Dardennes, Mike Leigh, Ken Loach, Andrea Arnold, et al.

Claudine, released in 1974, is almost certainly not the only example of a Black American melodrama from the era, but it is one of the most prominent of its time – earning an Academy Award nomination for lead actress, Diahann Carroll – and, yet, remains commonly overlooked within the pantheon of Great American Cinema of the 1970s.

Carroll plays Claudine, a single mother living in a realistically humble apartment in one of 70s New York City’s obviously non-affluent neighborhoods. Working as a housecleaner for a suburban white couple (a setting that could be drawn from a Sirk film), she initiates a friendship / romance with the family’s extroverted garbageman, Roop (James Earl Jones). In Roop’s first appearance, his enthusiastic, jolly demeanor threatens to be a portent of an ugly caricature of a happy member of the servant class but his “yes, sir” in response to the white homeowner is absolutely not deferential. The film is uncamouflaged in its use of racial / cultural stereotypes – Claudine is a welfare mother of six children from separate fathers, Roop is a largely absentee father to children of his own – but those are defiantly not the defining elements of their characters. As the cautious relationship between Claudine and Roop grows, the film doesn’t employ the sad tactic of endowing the characters with hearts of gold either. Though, the adults in this film are, to a significant degree, lost in and controlled by “the system”, they also make plenty of mistakes all on their own. Neither absolute heroes nor villains.

Claudine is billed as “a heart and soul comedy” and there are strong and appropriately placed comedic elements in it but those moments are more along the lines of laughing at the irony of existence than any sort of madcap hijinks. Like the “angry young man” films of the 1960s UK, the story is grounded in the problems that generally arise from the lack of money, opportunity, and stability in the working class. To this recipe, Claudine adds the struggle for civil rights and the Black Power movement, personified here in a terrifically skeptical and angry performance by Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs (Cooley High and Welcome Back, Kotter) as Claudine’s oldest son, Charles. His character’s misguided actions at the resolution again confront racial stereotypes from an unexpected direction.

All this and a ripping soundtrack from Gladys Knight and the Pips & Curtis Mayfield.

Matt Olsen is a largely unemployed part-time writer and even more part-time commercial actor living once again in Seattle after escaping from Los Angeles like Kurt Russell in that movie about the guy who escapes from Los Angeles.