Bela Tarr’s 7 1/2-Hour Satantango is Utterly Engrossing. Who Knew? By Craig Hammill

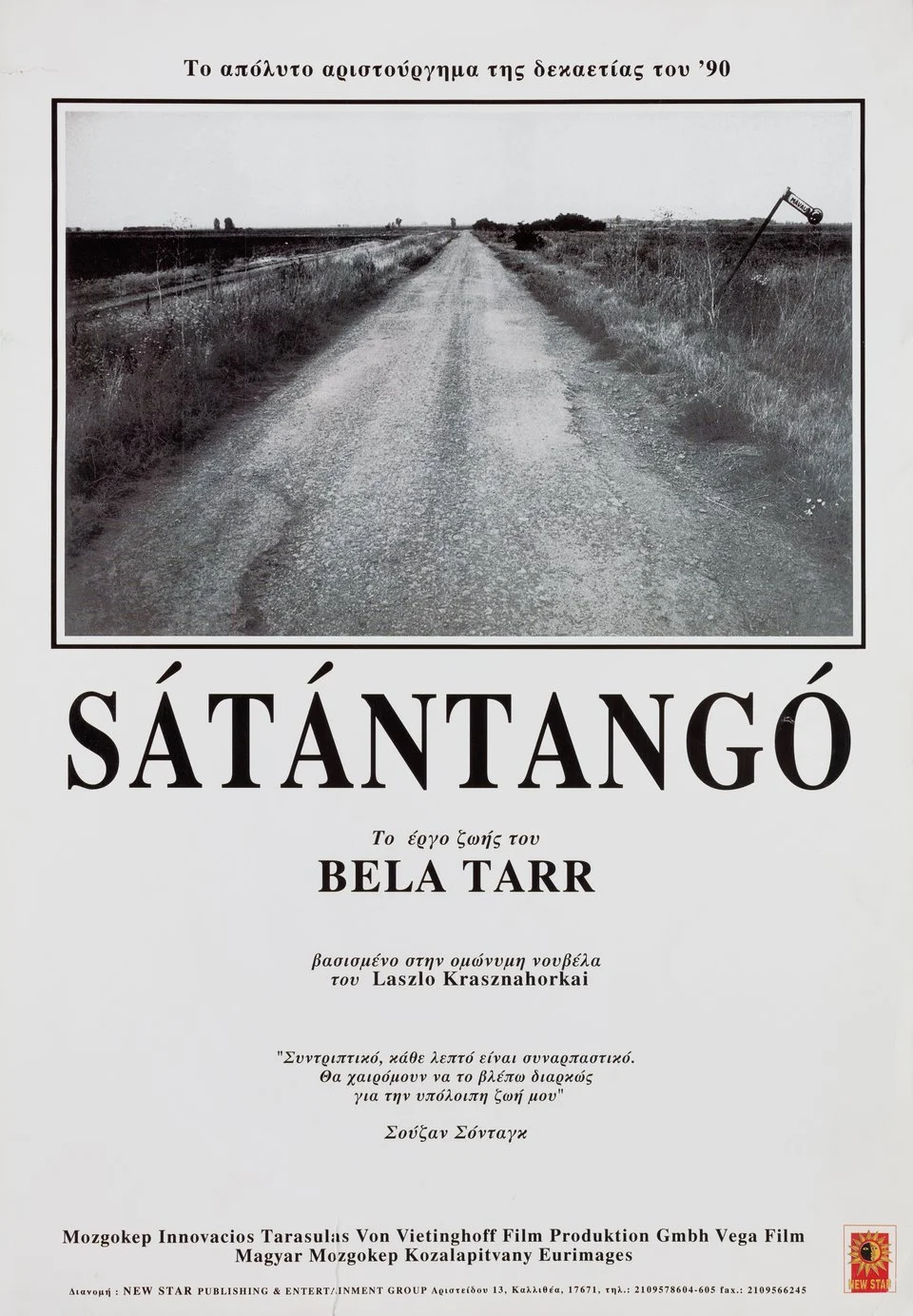

Hungarian filmmaker Bela Tarr’s 7 1/2 hour 1994 opus Satantango is oft whispered about in the halls of movie lovers as one of the great white whales of cinema watching.

Have you seen it? Do you know about it? What is it actually like to watch it?

And it feels understandable for anyone, prior to watching the movie, to have their suspicions that Satantango’s world cinema masterpiece reputation may rest somewhat on folks in the know patting themselves on the back that they actually made it through the entire experience.

Maybe a bit like a music lover holding up Lou Reed’s 1975 album Metal Machine Music (a 64 minute record of melody-less guitar and feedback noise).

But like many disproved pre-judgements, the enthralling, captivating experience of watching Satantango fully validates the movie’s place as one of the great works of the last fifty years.

If you’ve never seen or even heard of Satantango, it is a Hungarian film, based on a novel with the same name, about a group of disenchanted neighbors in a farm collective who get manipulated (yet again) by the return of a silver-tongued charlatan, Irmias, they thought dead.

But of course, like so many great works, the logline does no justice to the actual complex, layered, multi sub-plotted reality of actually ingesting the work.

The movie is divided into 12 parts or chapters and, like the novel, resembles a cinematic version of the tango itself-six steps forward, six steps back.

In the movie, we often get 2-3 chapters that move us forward in the narrative then come to a chapter that starts back at the beginning from a different perspective. Or shows us something that was going on at the same time we were watching a previous chapter.

The movie is shot in a bleak yet rich black and white and spends much of its time focusing on the palimpsest faces of its main characters: faces that convey lust, greed, pettiness, paranoia, megolomania, blankness, disappointment, regret, anger, worry...

As I sat watching the movie across the afternoon and into the evening (buffeted by two intermissions that are now baked into the presentation), I was struck by how engaged I was. It helped to watch with fifty other folks. Everyone was captivated by the movie and the act of watching it with an audience only amplified that engagement (as audiences at their best can do).

It’s quite possible had I tried to watch the movie on my own, I might have broken it up across days or even weeks. But the dirty little secret about Satantango is that it is actually quite easy to make it through its seven and a half hour run time.

The story-telling and narrative strategies are quite muscular. And the metaphors, themes, symbolisms that course through the movie are clear, well communicated, and well developed.

As the hours ticked off, I wondered, what makes this movie so engaging? One thing I felt was how successfully it created the same feelings you get when reading a novel.

In fact, it might even help to think of watching Satantango as more akin to reading a great 200-250 page novella.

Early in the movie, we see the false prophet and charlatan Irmias and his co-conspirator Petrina get an assignment from a police captain to return to the farm collective.

In the middle of the movie, we get a very unsettling sequence in which a troubled young girl, Estike, tortures her cat then takes rat poison, dies, and has what may either be a spiritual vision or a hallucination.

When Irmias has a similar vision (fog and mist running through buildings in the early morning), the movie’s own sense of mystery deepens.

Are both these characters delusional? Did they actually have some kind of spiritual experience? It doesn’t help that the two characters who do have visions have mental health and megalomaniacal issues respectively.

One of the centerpiece sequences of the movie occurs in and around this middle part when the child Estike witnesses most of the adults in the farm collective drunkenly dancing, pawing at each other, arguing, and passing out in a bar.

Bela Tarr’s genius throughout seems to be being able to both look at such behavior with a witheringly critical eye AND a non-judgmental, even compassionate one.

But we understand why children like Estike are not moved by nor admire their parents and adults around them.

When Irmias uses Estike’s death to deliver a speech that gets the farm collective to do his bidding (essentially give him all their money and leave the collective), we can’t help but cringe at a political opportunist taking advantage of a child’s death and a community’s vulnerability and ignorance.

Like the tango dance itself, the movie moves forward and back across theme as well: political opportunism, totalitarianism, manipulation, hypocrisy.

The famed opening long take shows cows wandering a town before disappearing into the fields. Immediately afterwards we are introduced to the townsfolk cheating and plotting against each other. And shortly thereafter they are exploited by a smooth talker.

In interviews, Tarr has often openly admitted he loves people but feels they are quite stupid . He also rails, in interviews, against the herky jerky political roller coaster ride of his native Hungary.

One fascinating character, the town’s doctor, who only seems to drink himself into a stupor and take obsessive notes on his neighbors’ actions, feels like a jab at intellectuals who may SEE more clearly the ills of a country, community, or society but often do very little about it.

In fact, Satantango at some center of its being seems to be a lament for this hard swallowed truth: those who see the ills of society and political systems often do little to change them and those who change society often do so out of self-interest, megalomania, and opportunism.

And the rest of us are somewhere in between at the whims of the winds.

There’s so much more to Satantango than these paltry thoughts put to paper. There’s a mysterious essence and examination of the soul and human nature that is irreducible in the movie. This too may be part of its strength and power.

But it is also, surprisingly, a funny, funny movie. Including a late in the movie scene in which two bored police detectives reduce almost everything and everyone we’ve seen to palatable stereotypes to make a report short and digestible for their superiors.

Watching Satantango, whether or not you ultimately want to make cinema like the movie, invigorates and inspires. It reminds you that movies CAN be like this. That filmmakers DO DARE to do these things. And when they do with the full power of their talent and those of their collaborators, they make mysterious fascinating things.

Craig Hammill is the founder.programmer of Secret Movie Club.