ABSURDITY IN THE 21ST CENTURY PART 1: SORRY TO BOTHER YOU (Boots Riley, 2018) by Matt Olsen

ABSURDITY IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

Sorry to Bother You – (Boots Riley, 2018)

Centered around LaKeith Stanfield’s incredibly empathetic performance as Cassius Green, a man caught in a battle between success and compromise, Sorry to Bother You is a remarkably consistent first film (!) from writer / director, Boots Riley. That’s been said many times about this movie but it bears repeating. It’s extremely rare for something with this level of confidence in its execution to appear under any circumstance, much less as a debut. Not to diminish his efforts as a filmmaker at all, but I wonder if the genre characteristics inherent to absurdity are best suited to a non-traditionalist’s approach. Does relative inexperience (considered as a positive) stop a creator from second-guessing their most unconventional ideas?

StBY begins as a relatively straight-forward story. Beginning a new telemarketing job, Cassius attempts to find his place within the business’ unfamiliar culture. As the film develops, the eccentricities that had been lurking around the edges propel the plot toward its inevitably bonkers conclusion. Peppered throughout are quick hits of comedic non-sequiturs: a fully-uniformed high school football team running late night scrimmages on a darkened street corner; a physical abuse-based TV game show; a shared work/live space clearly modelled on the American prison system. Because these bits are so brief and not immediately tied to any obvious narrative, they feel a little like throwaway gags. Bitingly satirical throwaway gags. Turns out that’s a bluff, though. Nothing is nothing here.

The final act brings a wild resolution that connects Cassius to all of the previously disparate threads while adding a new, shocking element which jolts the film into completely new, yet entirely compatible, territory. Tying up the story strands in a way that feels natural and satisfying is always a challenge, heightened here as the story hinges on something purposefully un-natural. In spite of its outré turns, Sorry to Bother You is a film that remains entirely relatable on the level of shared human experience – most of us have had to temporarily shelve our strictest code of ethics once or twice in order to pay the rent. What makes this such a distinctive experience is how well it succeeds while veering between gruesome body-horror, a pointed satire of cultural inequities, and blatant absurdity. All of that and a happy ending. Temporary, though it may be.

PART 2:

Uncle Kent 2 – (Todd Rohal, 2015)

When is a sequel not a sequel? As the film’s poster’s tagline raves: “Nobody saw the first one, so he’s back for a second.” This is coupled with another declaration of intent: “Cool. Cinema is dead.” That remains undecided but taking those two mission statements together provides a fairly accurate pair of compass points to the direction this film takes.

Ostensibly, this is a film about Kent Osborne, the co-writer and star of Uncle Kent, hoping to make a sequel to the original Uncle Kent, clearly named after him. But, within and without this film, there are multiple levels of realities intersecting. Kent Osborne – in our world – is a writer and animator. In Uncle Kent, he also plays a writer / animator not too far removed from his real self. In Uncle Kent 2, he plays a third version of himself as a writer / animator who played a version of himself playing a version of himself in the original Uncle Kent. It’s convoluted but, thankfully, this film doesn’t ask you to do any math along the way.

The story’s framework sends Kent to the San Diego Comic-Con to appear on a panel promoting his comic and animated series, Cat Agent, which – unsurprisingly – is also a web series which exists on our Earth. The film repurposes Kent’s actual SDCC panel appearances and stages other scenes in the midst of the convention. Over the weekend, Kent grapples with the suspicion that he may be living in a simulation of reality. A theory which gains traction as people and things around him stop conforming to the physical laws of the universe.

Over the course of a fleet 73-minute runtime, Uncle Kent 2 cycles through animation, dream sequences, invisibility pranks, celebrity cameos, and even a giant animatronic lizard-creature in a quest to determine what, if anything, is real. I guess? Honestly, pondering the question of existence is not the key objective of this film, for me. Uncle Kent 2 is an exercise in the momentum of humor and surprise. Beyond any other ambition, it’s a wild, riotous whirlwind of action and ideas.

So, when is a sequel not a sequel? Maybe when nobody saw the first one and, presumably, it doesn’t matter even if you did. (I didn’t.)

PART 3

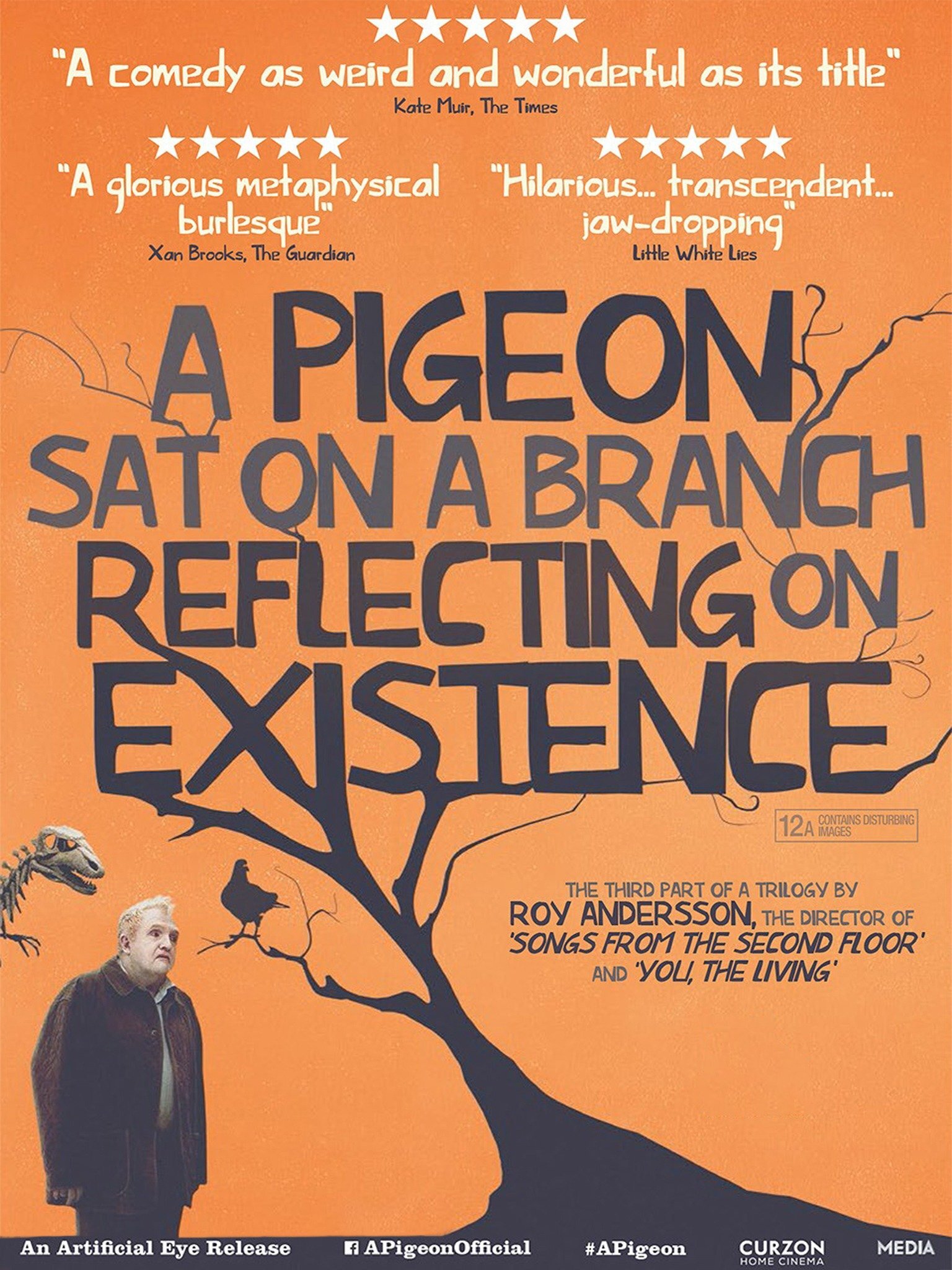

A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence – (Roy Andersson, 2014)

The third in the Swedish director’s “Living” trilogy, Pigeon is not a sequel in any traditional sense. But then, it’s also barely a movie in any traditional sense. Characters move around in locations, interacting with each other or not, much thought and care is obviously given to casting, set design, lighting, costume and make-up, and it’s about two hours long. Though, in every other way, Pigeon is much closer to The Far Side than The Blind Side.

Structurally, this is a film of some recurring and loosely defined storylines intermingled with one-off bits of unrelated characters repeating the same line of dialogue to an unseen person on the other end of a telephone line, “I’m happy to hear you’re feeling fine.” Each scene – with one exception – is shot with a static camera from a fixed point roughly the same distance from the “action” and they’re all in one take, generally several to many more than several minutes long. The lighting is flat and, purposefully, undynamic which highlights the relative colorlessness of the overall design. An aesthetic which bleeds through every facet of the film. Characters seem resigned to a mundane misery that, at times, feels like a caricature of Scandinavian stereotypes.

What isn’t clear from the above summary is how physically beautiful and surprisingly funny the movie is. A sometimes very grim, very black humor; buyer beware. The deliberately slow pace of the film ensures that attention is paid to the placement, construction, and quality of every item, person, or color in every frame while also allowing the audience time to explore its entirety. In this setting, intriguing background elements may only be noticed after several minutes. The overwhelming stillness heightens minor changes to a degree that they become comic. The smallest gestures carry the weight of a military parade on horseback storming into a diner. Though, that also happens. Some scenes are played for laughs, some for tragedy. The approach is consistent and effective, no matter the objective.

The adjective “deadpan” has frequently been assigned to certain comic actors but, in my memory, it’s never been considered a complete genre of film. Pigeon, along with the previous two in Andersson’s trilogy and, arguably, the work of Jacques Tati – especially PlayTime, make for a compelling case.

PART 4

Butt Boy – (Tyler Cornack, 2019)

When confronted with a title like Butt Boy any rational person would be more than justified in seeking their entertainment elsewhere. It took two isolated recommendations – one from a friend, the other from John Waters – for me to overcome that titular hurdle and give the film a chance. Right away I’ll admit this movie may not be for every audience. Though it’s important to note that the movie is both not nearly as graphic as assumptions may lead one to believe and incredibly audacious in its presentation. On several occasions I caught myself, awe-struck by the total commitment the movie maintains to its central idea. An idea which is unequivocally 100% juvenile, 200% ludicrous, and, yet, an inexplicably effective engine for something neighboring an area adjacent to the border running parallel to an intelligent comedy.

Like a modern-day Orson Welles, director / co-writer / lead actor, Tyler Cornack, maintains exactly the right tone throughout. For the characters trapped in this nightmare scenario, every moment is imbued with the level of gravity it deserves. Though the situation may be far, far beyond the pale, there isn’t any winking at the audience. In the midst of our astounded laughter, we can readily dredge up the necessary empathy to feel the torment these characters endure. Well, to a degree, at least.

Stylistically, it’s a skin-tight parody of the police detective vs. serial killer / cat and mouse game seen in films such as Se7en or Silence of the Lambs. But this isn’t one of those imbecilic movies that substitutes humor for a laundry list of cheap references. This is a truly original comedy – I guarantee you haven’t seen this story before – and it fully understands how to build tension as much as abandon reality. The photography, performances, and score compare with any straight thriller in a similar genre. Speaking in the broadest sense, of course, since there is no other movie in this genre.

Enough already. What’s it about? Right? To answer that for you would be a tragic mistake. Rest assured, it’s probably not exactly what you think and much more than you could ever predict. If you go into this film looking for logic, you’ll be disappointed. Butt Boy has less interest in making absolute correct sense than giving an unquestionably, wonderfully capital-D dumb idea the highest honor possible: an actually funny comedy filled with genuine surprises. And audacity. Don’t forget to mention the audacity.

PART 5

Rubber – (Quentin Dupieux, 2010)

Though these films were not chosen in any particular order, it’s absolutely fitting that Rubber holds the last installment in this series as it reflects characteristics of each of the preceding.

Like Sorry to Bother You, Rubber Is also a film written and directed by someone who was previously best known as a musician. In this case, Mr. Oizo.

Like Uncle Kent 2, Rubber crosses, combines, and confuses multiple realities including the one in which the viewer resides.

Like A Pigeon Sat on a Branch…, Rubber offers a sharp but absolutely black sense of humor which prioritizes mood and pacing over rapid-fire gags.

Finally, like Butt Boy, Rubber is built on a central idea that is unreservedly ludicrous. In this case, a psychokinetic tire wreaks murderous havoc on a small desert town, somewhere in America. Yes, a tire. And, yes, exactly.

Why a tire? The answer is clearly found in an introductory monologue delivered directly into the camera by a character representing a figure of authority. The local sheriff contends that every one of the greatest films in history – from E.T. to The Excellent (sic) Chainsaw Massacre to The Pianist – embrace the concept that things happen for ‘no reason’. We are further instructed that ‘no reason’ is the most powerful element of style. Clearly, tongue is firmly planted in cheek and taking that also into account, it’s serves two purposes: as an absurdist’s manifesto and an effective tool to immediately broadcast that this will not be a passive audience experience. If it weren’t clear enough, this idea is doubled down by the presence of an actual corporeal audience watching the story from within the story. Throughout the film, this audience picks apart and comments on the supposed main storyline. Significantly, their reactions are not always positive. When the filmmaker strikes out against this audience, is it revenge? Or an act of desperation? Has he surrendered to the film itself?

Half of the humans in this story are either implicitly aware or willing to consider that they exist in a movie (on some level of their existence). Naturally, a certain number will always refute the concept. Here’s yet another mirror to the audience experience of watching a film. Anyone watching a movie understands that what’s on the screen isn’t real but for those that allow it to affect them, they convince themself to pretend that it is. At least, to a degree. Otherwise, who would ever believe that a tire has the power to explode people from the inside-out? And why would anyone care?

But, about that tire. However it was accomplished, the effect of watching a tire propel itself across the desert floor, through doorways, and into a swimming pool is remarkable. There’s some invisible element of puppetry involved which even further muddies the lines between what’s a movie and what’s the making of a movie. The tire absolutely has a distinct personality despite it being, you know, a tire. No wheel-well, hubcap, or inner tube. This is a villain with no moral center – or any center. Again, it’s a tire. It exists only to kill. Why? How? No reason.

Matt Olsen is a largely unemployed part-time writer and even more part-time commercial actor living once again in Seattle after escaping from Los Angeles like Kurt Russell in that movie about the guy who escapes from Los Angeles.