A SYMPHONY OF PERSPECTIVE: Ezra Edelman's doc O.J. MADE IN AMERICA (2016)

Nicole Brown Simpson was 35 years old when she was brutally murdered June 12, 1994.

Ron Goldman, a friend of Nicole’s, was 25 when he was brutally murdered June 12, 1994.

Ezra Edelman’s 7 1/2 hour ESPN 30 x 30 doc O.J. Made In America (2016) is as one of a kind as the story it tells. Made as a television miniseries for ESPN’s superlative 30 x 30 documentary program, it screened at the Sundance Film Festival before it aired on television. It later went on to win the Best Feature Documentary Academy Award.

The documentary, save for a few bumps and the occasional over-reliance on drone shots of Los Angeles court buildings (the only time you are reminded of its television roots), is superlative. Its core strength comes from its determined commitment to give all perspectives and viewpoints their due.

Edelman DOES have a point of view and a thesis. But he also has that rare gift: the ability to let the truth be the truth and speak for itself. And an understanding that there are multiple truths: the clash of such competing truths produces an even bigger truth.

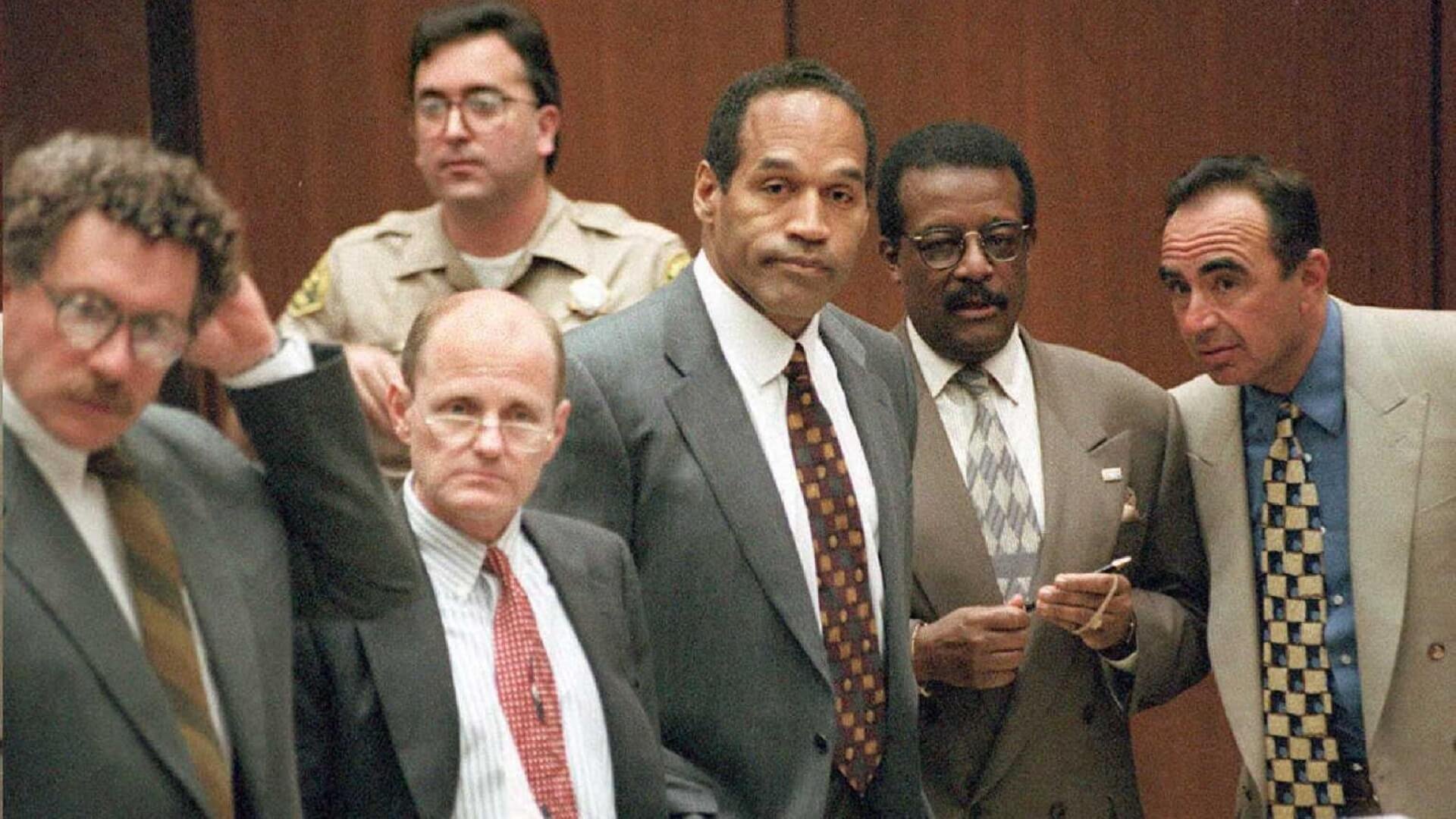

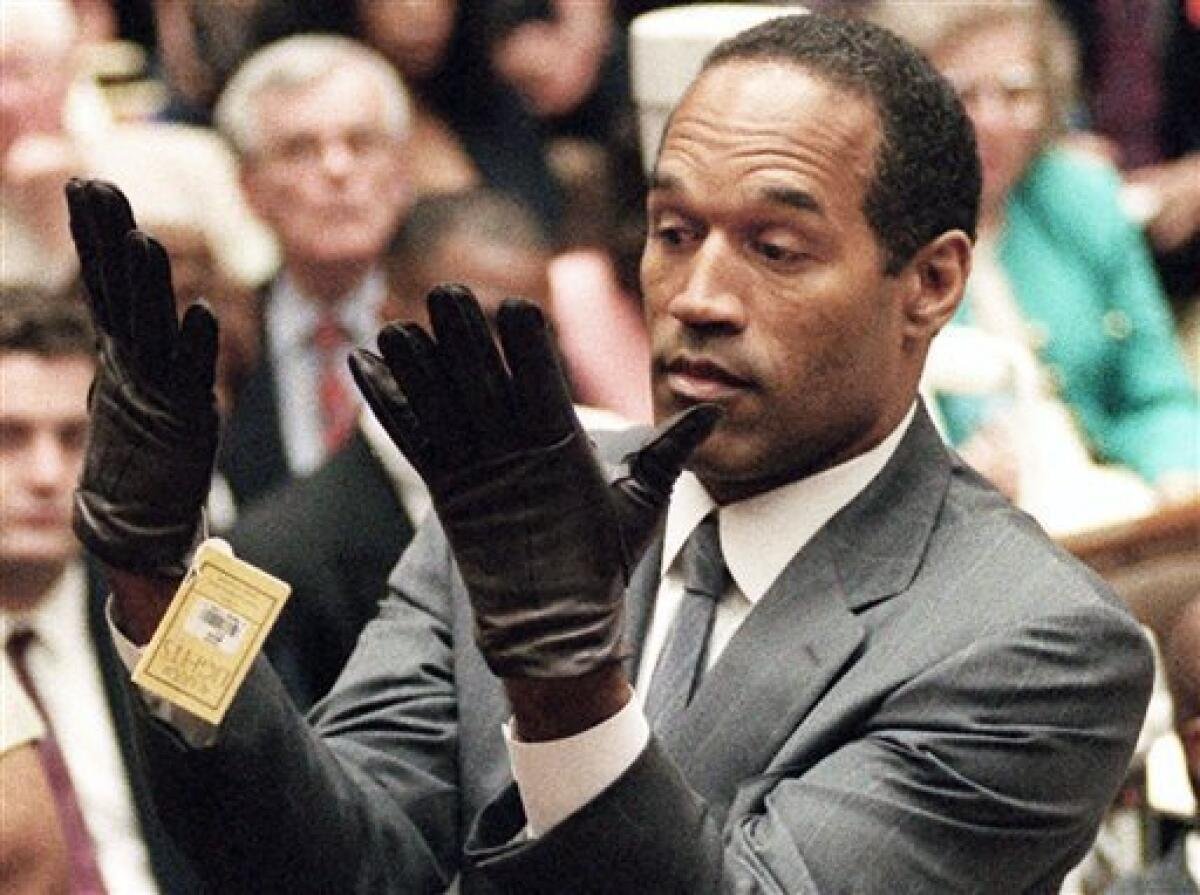

The documentary at its heart revolves around the famous 1994-1995 “Case of the Century” where famed football athlete, actor, beloved American O.J. Simpson was accused of murdering his ex-wife Nicole Brown Simpson and her friend Ronald Goldman. The case was televised, gripped the nation, and became a racial litmus test on one’s understanding of the American criminal justice system .

O.J. was found not guilty despite a preponderance of evidence pointing to his guilt.

Filmmaker Edelman, himself the son of a black mother and a white father (which may explain his ability to empathize with so many viewpoints), takes a kind of ten thousand foot altitude view of the case. He is much more fascinated with the broader complicated frame than just the specific lurid details.

He gives us an in depth history of O.J.’s life up to that point. He explores race relations and the black community’s relations with police in Los Angeles. He shows how many African Americans were still furious over the brutal 1991 beating of black motorist Rodney King at the hands of white police officers who were eventually found “not guilty” despite abundant video evidence.

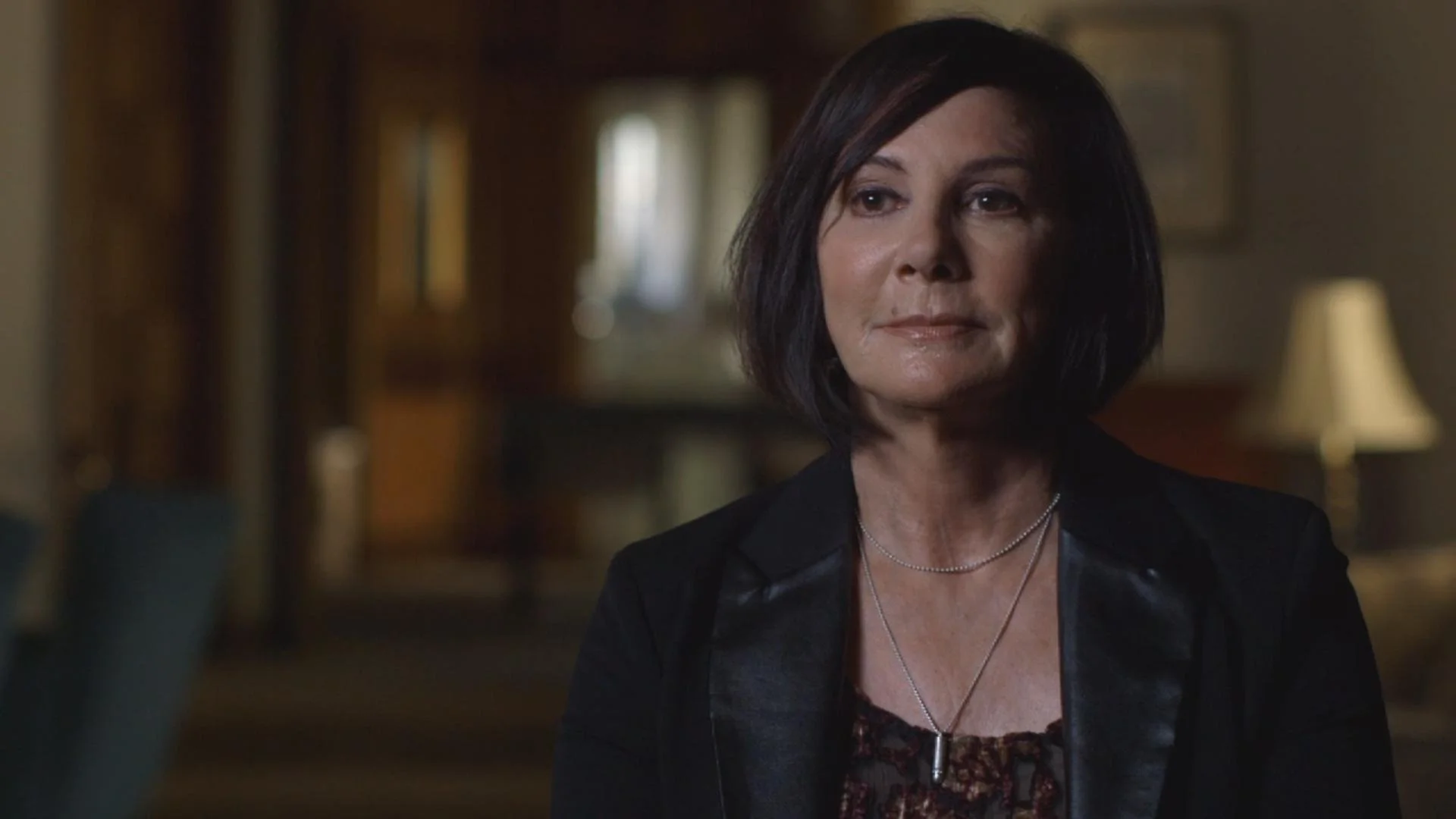

Lead prosecutor Marcia Clark, like so many of the interview subjects, provides fascinating perspective, commentary on the case.

And all throughout, Edelman somehow manages to get in-depth interviews with many of the key figures of the case. It’s almost shocking to hear police detective Mark Furman, prosecutor Marcia Clark, Fred Goldman, the father of the slain Ron Goldman, O.J. friend Ron Shipp, Jurors who found O..J. not guilty, writer/legal analyst Jeffrey Toobin all given serious respect and a platform to air their thoughts, perspectives.

And Edelman, to his credit, refuses to editorialize through editing to show who he favors or does not favor. Rather Edelman works to give these voices a fair platform to communicate their perspective which elevates his documentary to the top tier of the art form.

Mark Furman, the vilified LAPD detective, whose past racism came to light during the trial, is surprisingly self-aware in his interview.

So many documentarians (and filmmakers) even when working in a supposed even-handed “cinema verite” style still can’t resist the urge to put their finger on the scale. But Edelman comes at the subject matter here like it’s a Tolstoy novel (which it is in some ways) and trusts that the cumulative effect of the documentary will be much richer if he orchestrates a symphony of perspective rather than fall in the trap of elevating his own as a director.

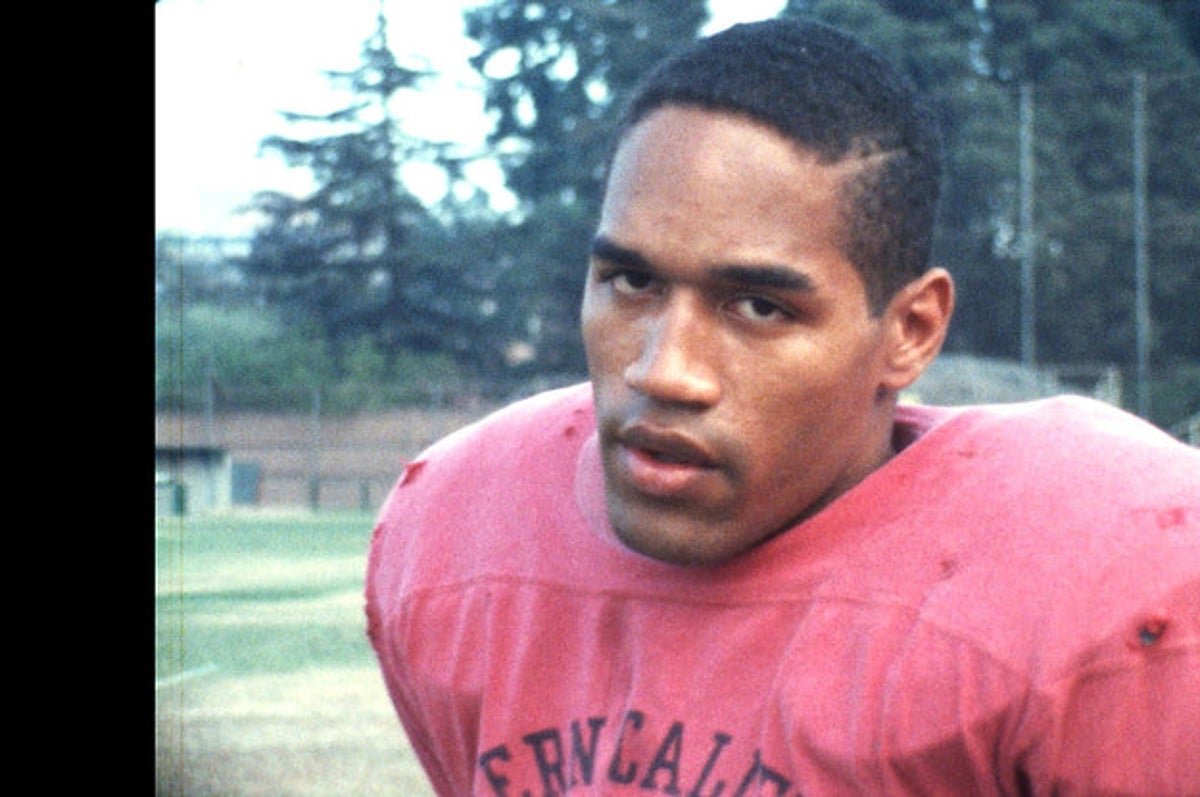

For decades, O.J. was, rightly, a role model and hero to millions. He parlayed his football success into a successful business, marketing, and acting career.

Edelman DOES have a point of view and a thesis. Ultimately O.J.: Made in America as its title implies proposes that the trial was about much bigger things-celebrity, race relations, the systemic inequities of American justice, self and national delusion-than just a tragic double murder that churned years of salacious media cycles (it was that also).

While the documentary probably could have been 30-60 minutes shorter than it is, it gets better and better as it goes along until, in its final episode, the tragedy somehow mixes with farce to become absurd.

O.J. Simpson (as the doc presents him) is a kind of self-made American who rises to the very heights of success through his athletic ability, work ethic, and charisma. Simpson parlays these traits after his retirement from the NFL into an acting, business, and commercial career. All the while, the doc points out, that O.J. distanced himself from the issues of the black community. O.J. always wanted to be seen as “O.J.”, “The Juice”, his own person. Unlike athletes like Mohammad Ali who went to jail for their beliefs and spent their entire lives speaking out against injustices against Black Americans. O.J., by comparison, prided himself on transcending race and staying out of such frought national debates.

O.J.’s “Dream Team” of attorneys found numerous ways to speak to the inequity of race in the American justice system throughout the trial.

The irony here is that when O.J. assembled his “dream team” of attorneys for the murder trial, they all intuited that race, the LAPD, how many of the black jurors would feel about a black man being tried for the killing of a white woman, etc would be key to a successful defense.

The double irony is that O.J. as a lifelong celebrity always had people around him willing to get him out of fixes. So one comes to understand how the beast of fame and celebrity can also distort one’s own sense of character/integrity/accountability.

The doc does an admirable job of communicating a number of thorny and unsettling details while weaving it into a larger narrative. We get a history of LAPD’s horrible treatment of African-Americans. We hear about O.J.'‘s and Nicole’s abusive troubled relationship which included numerous 911 calls for domestic abuse. We see the weird circus frenzy like atmosphere that always arises around celebrity cases like this.

And yet Edelman goes to great lengths to make a fascinating, ironic central point that is voiced best by novelist Walter Mosley in the documentary. The fact that O.J., a black man, was found not guilty of killing a white woman by the American justice system, is ‘de facto’ progress in American race-relations regardless of O.J.’s ultimate guilt or non-guilt. The American justice system has failed black America so many times that O.J.’s “not guilty” verdict was a kind of catharsis. Paradoxically, white America couldn’t believe someone so clearly guilty was let off.

O.J.s fall from “beloved athlete” to “vilified murderer” in the eyes of white America is more a comment on White America than White America wants to admit.

But that seems to be exactly the point of the documentary: white America still has very little understanding of how this very thing (someone guilty being let free) has happened thousands if not millions of times with white perpetrators of violence against innocent black victims.

Still, Edelman seems to feel that O.J. is guilty. And it’s hard not to come to that conclusion with the near unbearable fifth and final episode where you see O.J. do very little to try to find Nicole and Ron’s “true killers” as he had promised to do, ignore his children, and descend into a cringey life of cocaine, strip clubs, groupies, prank TV shows (you can’t make it up) which ultimately leads to his strange arrest for armed robbery in Las Vegas.

Even here, Edelman has a genius for nuance and subtlety. Even this writer had thought O.J. robbed at gunpoint some kind of memorabilia convention. But what actually happened was a sloppy, cocky O.J. bringing friends to scare some folks who he felt had stolen his property. O.J. got a ridiculous 33 year sentence for what should have been a 2-3 year sentence tops. And here Edelman and his interview subjects make the point that in some ways the white justice system was getting back at O.J. Something lawyer Carl E. Douglas refers to as “the fifth quarter”.

Lawyer Carl E. Douglas who served on Simpson’s “Dream Team” is one of the most memorable interview subjects in the documentary. Douglas introduces the term “the fifth quarter” in the finale episode as a way of explaining how his inner city high school team might lose in the fourth quarter but would then find the opposing team and beat them up in the streets. That was known as “the fifth quarter”.

It’s all as disheartening as it is fascinating. O.J. and the media frenzy inaugurated some kind of American era that has only gotten worse with time. Too many successful politicians and influencers of our era seem to embrace the ethos that truth and facts don’t matter any more. What matters is perception and performance, lots of money, and lots of lawyers.

But then again maybe it was always that way.

And finally the documentary does an admirable job of humanizing Nicole Simpson herself (not so much Ron Goldman unfortunately). Society has a horrible glitch about it in that the murder victims are often the most forgotten part of the murder cases. It’s often the colorful living characters surrounding the murdered who get discussed. Meanwhile two lives were robbed. Children were robbed of a mother. Parents were robbed of a son.

O.J., for all his flaws, is a fascinating tragic figure (something Edelman seems to understand profoundly). Simpson was a role model. He DID have incredible talent. He clearly HAS tremendous charisma. But he also appears to suffer from a mind-numbing amount of self-delusion. Like so many of us, O.J. seems more concerned finding a way to believe his own lies than getting right with his soul by confronting the hard truths.

What Edelman does so well, what’s so hard to do in documentary and fiction narrative, is illuminate how systems work. How we individuals are parts of much larger systems-race, class, legal, civic, etc. And how we often make the mistake of thinking our perception is an objective or even mostly informed one. When instead we’d do well to remember our perception is a limited and inadequate one.

Edelman’s documentary ultimately makes you aware there are many forces, traumas, currents, cross currents that course through the oceanic tides of civilization. And we’d all be wise to be humble and open to learning/empathy/understanding in the polyphony of perspective.

Craig Hammill is the founder.programmer of Secret Movie Club.