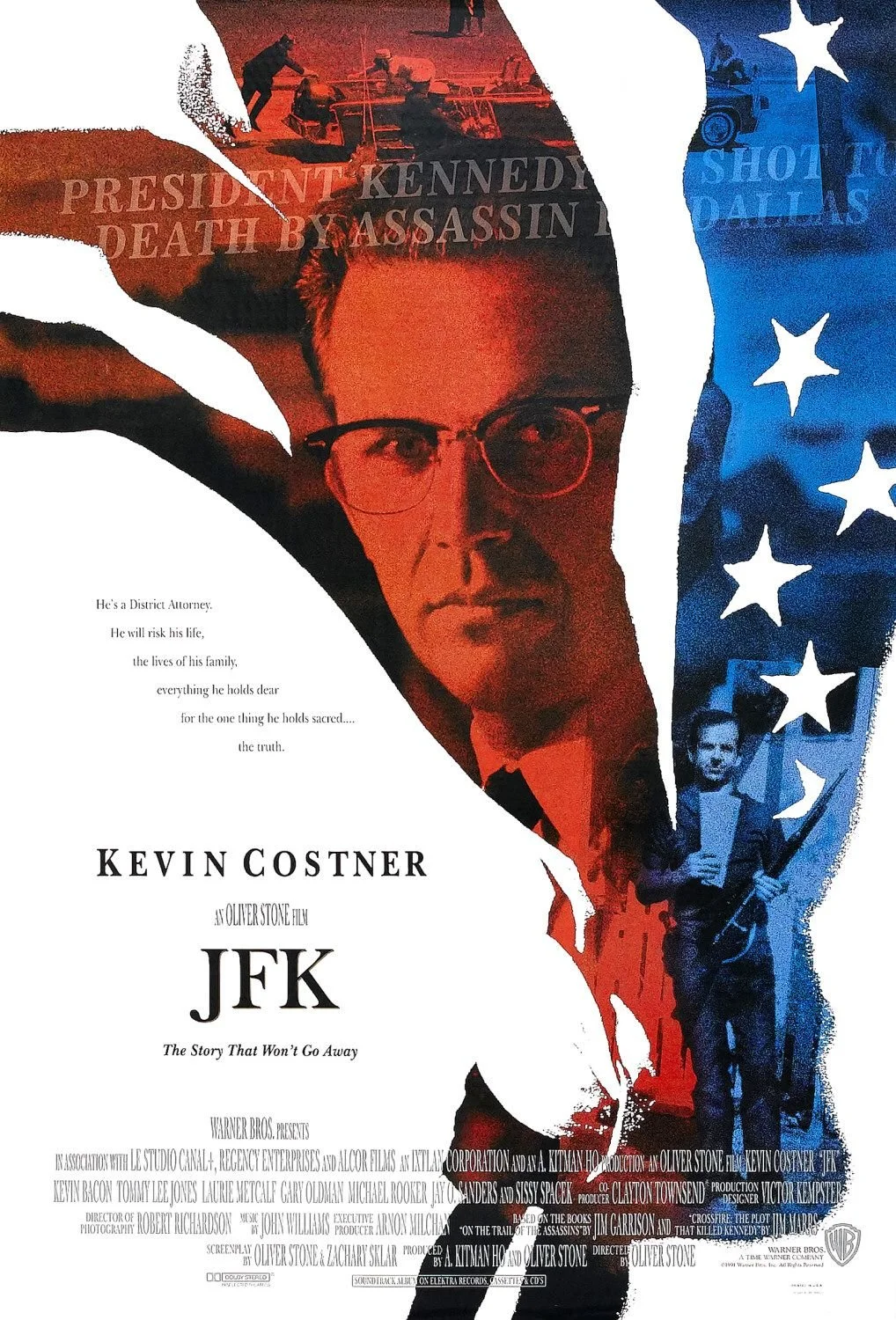

A POLITICAL SEASON: Occasional 2024 series on politics in movies JFK (1991, co-adap/dir by Oliver Stone, USA, 188mns-original theatrical cut)

Oliver Stone’s 1991 JFK about New Orleans district attorney Jim Garrison’s real life decision to try to prosecute local businessman Clay Shaw for being an accomplice to a vast conspiracy to kill President John F. Kennedy is ONE of the great American cinematic works of the 1990’s.

The conundrum. . .the “riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma” (one of the quotable lines from the movie voiced by Joe Pesci’s alleged co-conspirator David Ferrie) is that the movie somehow achieves its aim while itself being as factually flawed and manipulative as the supposed cover-up it rails against.

Maybe put another way: JFK is a consummate work of cinematic art that raises vital, important questions about lies sold to the American public while at the same time itself not playing straight with the facts.

This has often been at the heart of the debate of how narrative fiction moviemaking adapts, changes, structures, tackles non-fiction events. The tension is that to make something dynamic as a movie, one often has to create or combine characters, scenes, etc that did not occur EXACTLY in real life. BUT in doing that, movies open themselves up to accusations that this manipulation invalidates whatever themes, questions, ideas the movie was trying to raise in tackling the real life event.

Facts and truth. Narrative and fiction. They are unwieldy things. And they meet at an unwieldy wild and weird crossroads.

One of JFK’s greatest strengths is also one of its most controversial aspects: it seamlessly intercut archival documentary footage with re-creations thus making it hard to distinguish what was actually recorded in 1963 and what was shot for a movie made in 1991.

For anyone not super up on the bullet point facts of the assassination of our 35th president, John F. Kennedy, on November 22, 1963 in Dallas, Texas, Kennedy was shot and killed during a motorcade parade. The conclusion almost immediately agreed upon was that the murder was the work of a single gunman, Lee Harvey Oswald, who, it was reported, fired three shots from the sixth floor of a book depository building where he worked. One of those shots hit the President in the head and killed him.

Oswald denied the shooting when he was arrested. He never got to say much more as he himself was killed during a police escort by local nightclub owner Jack Ruby just two days later. Ruby maintained until his own death in prison in 1967 that he had shot Oswald out of anger for Oswald’s killing of the President.

President Lyndon B. Johnson had the Warren Commission, headed by Supreme Court Justice Earl Warren, investigate the assassination. The Commission’s conclusion was that Oswald WAS the sole assassin. And that there was no credible evidence of other shooters or a larger conspiracy.

The problem was that many pointed out that audio recordings, a famous Super 8mm film now known as the “Zapruder” film which documented the event, and eye witness accounts all pointed to the involvement of several other shooters from different locations.

The conspiracy theory is that JFK was killed in a triangulation of crossfire to GUARANTEE his death. Many feel that it would have been technically impossible for Oswald to have fired all the shots, caused all the bodily damage later documented.

To this day, a large swatch of the American public believes there WAS a larger conspiracy and possibly other shooters. This suspicion isn’t helped by the fact that subsequent presidential administrations (including Donald Trump’s and Joe Biden’s) have decided to keep thousands of documents about the assassination classified.

BUT. . .it must also be noted that over time, more and more folks who have looked into the JFK assassination have come to the conclusion that Oswald probably acted alone.

Nevertheless, Oliver Stone fashioned one of his best, if not HIS best, movie around the belief that THERE was some kind of cover-up. Stone, who had one the great modern runs as a moviemaker, was hot off Salvador, Platoon, Wall Street, Born on the Fourth of July when he made JFK.

Stone, cinematographer Robert Richardson (later to lens many of Quentin Tarantino’s big movies), and editors Joe Hutshing and Pietro Scalia, came up with a brilliant formal approach to the movie. Just as the movie is a story about a conspiracy, a mystery to be solved, to be investigated, so to is the style a kind of jigsaw puzzle of different shooting techniques (color, black and white, classical, handheld). The bravvura editing breathlessly examines, re-configures, cross-cuts between all these different pieces.

The movie is just over three hours long (the director’s cut is a bit longer but we’re writing about the original theatrical cut) but feels like it’s ninety minutes.

Finally, the movie also soars because of its all-star cast. Kevin Costner plays DA Garrison as a kind of political sleuth version of To Kill A Mockingbird’s Atticus Finch. Sissy Spacek is Garrison’s loving but harried wife. Joe Pesci is one of the hyped up co-conspirators. Tommy Lee Jones plays Clay Shaw, the local New Orleans businessman charged with being a conspirator. And then Jack Lemmon, Walter Matthau, Donald Sutherland, Kevin Bacon, Ed Asner, among many other greats pop up and make the most of their roles. Most importantly, Gary Oldman slays it as Lee Harvey Oswald. The movie really is a kind of Robert Altman-esque riff on the political thriller.

Is Gary Oldman bad in anything? Oldman said that Stone gave him money and plane tickets to research Oswald. And that Oldman got to create the character completely on his own. Oldman still refers to JFK as one of his greatest acting experiences.

The problem with the movie, as has been pointed out by countless historians and folks concerned with the actualfacts, is that Oliver Stone plays with the facts just as recklessly sometimes as the very people Stone indicts for doing the same in the cover-up.

For example, one of the movie’s most famous scenes has Joe Pesci’s David Ferrie ADMITTING to the conspiracy and acknowledging that Clay Shaw was involved. However in Jim Garrison’s own book about his investigation, he clearly states that Ferrie denied knowing Oswald and never admitted to anything. Garrison believed Ferrie was lying. But Ferrie made no admission.

Stone presents a scene in which we the audience get a kind of cathartic “Gotcha” revelation that never happened in real life.

Now that’s totally understandable from the point of view of re-fashioning material into a dynamic movie story. But it’s problematic if you’re presenting such a scene as fact.

In order to really sell to the movie going public that THERE HAD TO BE a conspiracy and cover-up, Stone plays with the facts as much as he accuses the Warren Commission of playing with the facts.

And so the argument goes, do two wrongs make a right?

Thus you have to go into the movie knowing that Stone is presenting a counter-narrative but NOT a definitive narrative based on fact.

Also, once you watch the movie a few times, and then do your own research, you do question the wisdom on the part of DA Garrison of bringing the case to trial with very little supporting documentation, witnesses, testimonies, etc that would have actually helped his case.

The movie implies this was because the conspirators did everything they could to kill anyone or alter records that would have helped Garrison. The truth may have been that Garrison’s case was flimsy.

The third act of JFK is the court case that DA Jim Garrison (played by Kevin Costner) brought against local New Orleans businessman Clay Shaw (played by Tommy Lee Jones). As a court case, it may have always been flimsy. As a structuring device to allow Stone the ability to present a bunch of information about the assassination in a dynamic dramatic way, it was a masterstroke.

Also, the movie has a kind of idealistic notion that had Kennedy lived the next forty years of American history might have been vastly better and unblemished. No Vietnam war. No Nixon. No Watergate. A de-escalation of tensions with the USSR, world peace. . .

Like so many things in life, it’s much easier for us to invest our hope and faith in things we don’t really have to prove or grapple with then in things that then get road tested and prove to be fallible.

One of writer Stephen King’s greatest novels 11/22/63 (published in 2011) deals with a time traveler who goes back to stop the assassination. But King, also known as an ardent liberal and optimist in many ways, comes to the conclusion that a counter-history in which Kennedy lived could have been just as bad if not worse then the one we actually have in the history books. There’s just no way to know.

So JFK the movie also suffers from Stone asserting an alternate outcome that can’t in any way be tested or proven.

What makes JFK so important in American political cinema is much the same reason why Alan J. Pakula’s All The President’s Men (made in 1976) is so important. Both Stone and Pakula found ways to bring crucial political debates into the pop culture dialogue by harnessing the tools of popular moviemaking and making POPULAR MOVIES. Both JFK and All The President’s Men were propulsive hits.

This then is their dirty little secret: many folks probably went to see the movies and were entertained as hell and left. . .and never thought about the underlying thematics again. And those who did were probably primed to do so with or without the movies.

This isn’t to condemn the movies with back handed praise. They are both works of art and critical movies in the American canon.

Paddy Chayevsky and Sidney Lumet understood the critical importance of entertaining when they made the blistering TV satire Network. Billy Wilder understood that when he made the “dog that bites the hand that feeds him” Hollywood takedown Sunset Boulevard. And Oliver Stone gets that here.

Frank Capra always said the cardinal sin in moviemaking is to be boring.

JFK is the opposite. It is wildly entertaining. Almost too entertaining.

But it does also stick the landing in getting us to question whether we should immediately accept as gospel truth what gets told to us by our media, our government, our political side, our social media., our chosen media ecosystem.

Shakespeare said “Modest doubt is the beacon of the wise” (Troilus and Cressida). But it’s hard to always have that modest doubt filter ready to go with the endless barrage of claims that come our way in our hyper-charged instantaneous media reporting age.

Facts are strange and unruly things. They know no political side. They aren’t composed to benefit the victor and punish the wicked. They just are.

Possibly the US government has struggled with the actual facts of the JFK assassination and that’s why they keep them classified. Possibly Oliver Stone struggled with how to take the facts and turn them into a compelling narrative to prove a thesis and that’s why he manipulated them when he made JFK.

Possibly we struggle with the facts because they frustrate the narrative we want to invest in in trying to make sense of the world.

To some extent, life and art are both the records, sometimes victorious, sometimes tragic, often somewhere in between, of our struggle to show strength of character and engage with facts and truth that are often beyond our own ken.

JFK may be flawed for many reasons. But it DOES ultimately succeed on its most fundamental level. It wants us to question what we’re told rather than blindly accepting it. A democracy can only survive if we all, as citizens, take some ownership in investigating what’s being “sold” to us. In campaigns. In governmental actions. In speeches. In commentaries.

The moment we give up being skeptical because we’re just too tired is the moment the democracy dies.

Craig Hammill is the founder.programmer of Secret Movie Club.