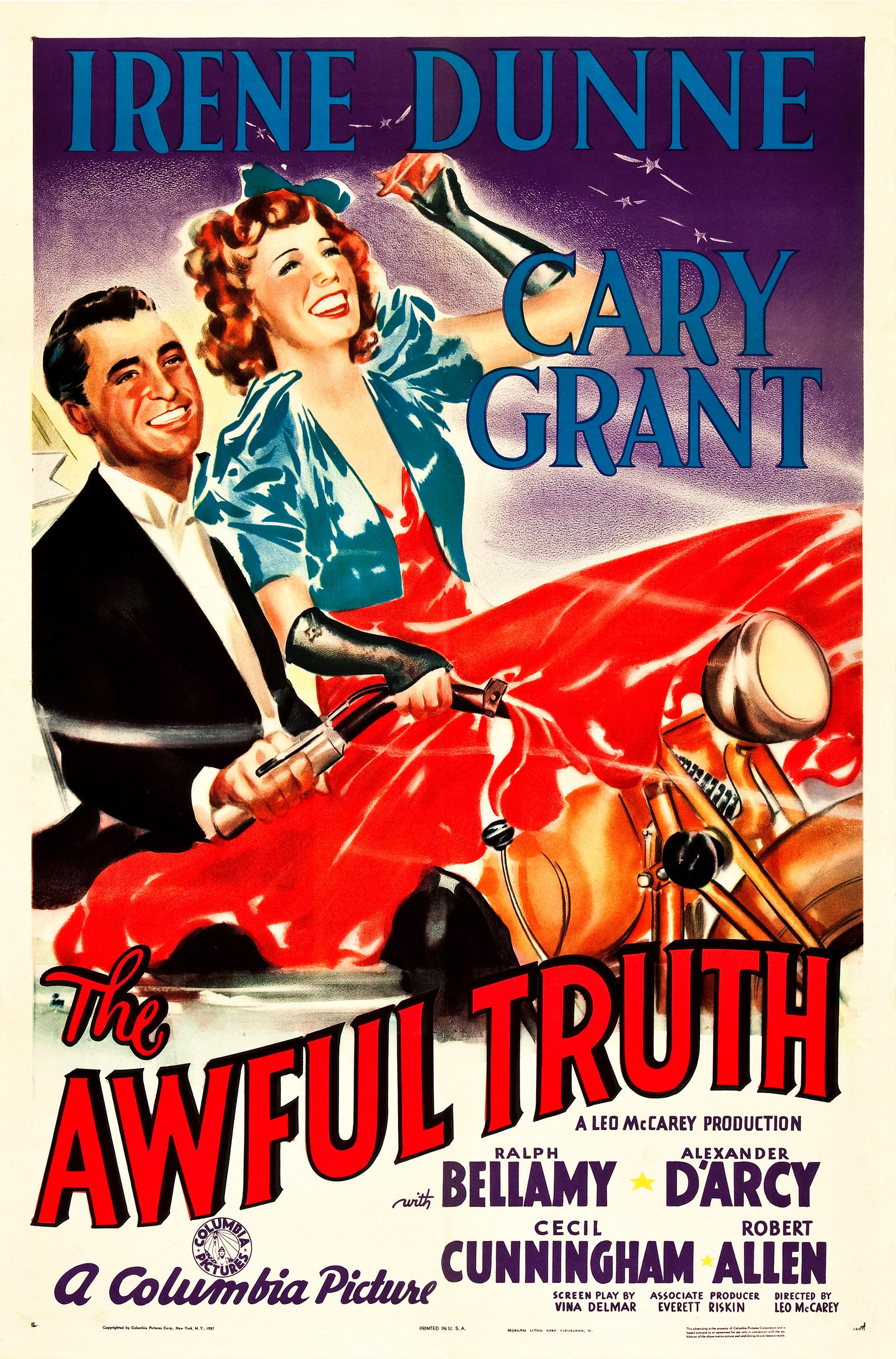

Irene Dunne & Cary Grant: The Awful Truth (1937, dir. Leo McCarey, US) by Matt Olsen

In the four-year span from 1937 to 1941, Irene Dunne & Cary Grant co-starred in three different films, from two different studios, and three different directors. Two comedies (The Awful Truth and My Favorite Wife) and one difficult to classify melodrama/tragedy/romance (Penny Serenade). Though they’d already had, and would continue to have, widely-acclaimed and popular success on their own – Dunne with Love Affair and I Remember Mama, Cary Grant with, well, being Cary Grant – there is a particular kind of crackle between them in these three films that is as exciting as exists in any of the more often heralded movie partnerships of Hollywood’s Golden Age: Hepburn & Tracy, Powell & Loy, Hope & Crosby, etc.

Their first film together was The Awful Truth, a classic screwball comedy that wastes very little time presenting and pushing through its premise to get to the chaos. Dunne & Grant play a New York cosmopolitan couple who resolve to end their marriage which has fallen into neglect, suspicion, and (probable) betrayal. After the paperwork has been filed, custody of the dog (Asta!) decided, and new living arrangements sorted, the two must wait sixty days for the divorce to become final. It’s in that waiting period that the heart of the film occurs.

At the start of the second act, it’s Dunne’s character, Lucy Warriner, who drives the narrative. Though she seems content to spend the two months reading magazines, holed up in the apartment she shares with her Aunt Patsy, a chance elevator meeting upsets the status quo. Soon, Lucy finds herself involved in a budding involvement with Daniel Leeson, a sweet but intellectually shallow oil millionaire from Oklahoma played by Ralph Bellamy, himself a three-time co-star of Dunne’s. Grant’s character, Jerry Warriner, observes their courtship largely from the sidelines with a vigorously arched eyebrow and smirk. It’s obvious that Lucy’s attraction to Daniel is tepid, at best. He’s a classic rebound; safe, consistent, deferential, and, simple. In essence, Jerry’s opposite.

Lucy generally responds to Jerry’s impishly malicious disruptions with a signature expression of Irene Dunne – a vexed glare over a wrinkled nose. It’s pure magic and belongs in the Film Faces Hall of Fame alongside Walter Matthau’s jowls of exhaustion and disbelief at the end of The Taking of Pelham 123 and Holly Hunter’s frozen mask of maximum intensity throughout the entirety of Raising Arizona.

Owing to a series of complications – such as one finds in the screwball comedy oeuvre – Lucy and Daniel’s engagement terminates and the third act becomes a boisterous role reversal of the second. After the close call with Daniel Leeson, Lucy acknowledges to herself that she’s still hopelessly in love with Jerry. Inconveniently, her soon-to-be ex-husband has taken up with a new lover. It’s up to Lucy to sabotage his developing relationship for the sake of her dying marriage.

It’s here that the film really goes off the rails. To this point, the majority of the humor has been largely verbally-based (with some key exceptions!) and relatively restrained. The last half-hour is an collage of pratfalls, noise, and even, at the end, a break with reality itself.

One key element that stops the film from becoming merely a live-action cartoon are the performances and, specifically, that above-mentioned frisson between the two leads. That the dialogue bounces back and forth between Dunne and Grant at a quick clip is not surprising. It’s all of their accompanying gestures, sounds, and expressions that make these characters seem real and alive in spite of the absolute absurdity around them. They uppercase-k know each other.

There’s a moment with Lucy (in the guise of Jerry’s make-believe sister, Lola) performing a ribald song and dance number at a gathering of humorless, wealthy elites, including Jerry’s fiancé and her parents. Lucy’s clear intent is to play the embarrassing relation to such a degree that it will mark Jerry as utterly unmarriable within that society. As she reaches the third verse, Jerry’s irritation breaks and he laughs. It’s not a guffaw. It’s a normal, private chuckle of recognition as if to say, “Yes, you’re right. This is ridiculous.” And isn’t that the fundamental truth of any successful relationship?

Matt Olsen is a largely unemployed part-time writer and even more part-time commercial actor living once again in Seattle after escaping from Los Angeles like Kurt Russell in that movie about the guy who escapes from Los Angeles.